When I am at large in deer country, there is no need for friends to try to lure me off the fascinating following of the whitetail by promises of more abundant sport with smaller game. Quail and ducks and woodcock and the like do not look very good when a man feels that an old buck with majestic antlers is waiting in the woods for someone to talk business to him. I admit that the game of deer hunting is sometimes tedious, and the shooting of the occasional variety; yet my experience has been that the great chance does come to the faithful, and that to make good on it is to drink one of life’s rarest juleps, the memory of whose flavor is a delight for years.

It may be that this love of deer hunting was not only born in me—the men of my family always having been sportsmen—but was made in growing by a curious happening that occurred when I was not a year old. One day I was left alone in a large room in the plantation house where first I saw the light of day. Lying thus in my crib, what should come roaming in but a pet buck that we had. My mother, in the greatest dismay, found him bending over me, while, if we may believe the account, I had hold of the old boy’s horns and was crowing with delight. I have always felt sure that the old stag (since he knew that his own hide was safe) passed me the mystic word concerning the rarest sport on earth. He put it across to me, all right; and I am going to do my best here to hand on the glad tidings. I want to tell about a deer hunt we had one Christmas not long past.

Things on the plantation had been going badly with me. There were plenty of deer about, and a most unusual number of very large bucks; but our hunting party had achieved nothing of a nature worth recording. We had been at the business nearly a week; and we were still eating pork instead of venison. That’s humiliating; indeed, in a sense, degrading. On a certain Wednesday (we had begun to hunt on the Thursday previous) I took our driver aside. It was just after we had made three unsuccessful drives, and just after some of the hunters had given me a look that, interpreted, seemed to mean that I could easily be sold to a sideshow as the only real fakir in captivity. In the lee of a great pine I addressed my partner in crime.

“Prince,” I said, drawing a flask from my pocket, “as deer hunters, you and I aren’t worth a Continental damn.” (This term, as my readers know, is a good one, sound and true, having been the name of a coin minted before the Revolution.)

“That’s so, sir, certainly so,” Prince admitted, his eyes glued to the flask, his tongue moistening his lips.

“Now,” I went on, “we are going to drive this Little Horseshoe. Tell me where to stand so that we can quit this fooling.”

The flask sobered Prince marvelously, as I knew it would. To him, there was no tragedy like seeing a drink without getting it; and the possibility of such a disaster made the good-natured man grave.

“This summer,” he said, “I done see where an able buck done used to navigate regular by the little gum-tree pond. That must be his social walk,” he further explained; “and that may be his regular run. You stop there, Cap’n, and if he is home, you will blind his eye.”

That sounded good to me. Therefore, the calamity that Prince dreaded might happen did not occur; for we parted in high spirits, and with high spirits in at least one of us. But there must have been a prohibition jinx prowling about, for what happened shortly thereafter appeared like the work of an evil fate.

As I was posting the three standers, the man who had already missed four deer took a fancy to the stand by the gum-tree pond. I tried politely to suggest that there was a far better place, for him, but he remained obdurate. I therefore let him stay at what Prince had described as the critical place. And it was not five minutes later that Prince’s far-resounding shout told me that a stag was afoot. Feeling sure that the buck would run for the pond, I stood up on a log, and from that elevation I watched him do it. He was a bright, cherry-red buck, and his horns would have made an armchair for ex-President Taft. He ran as if he had it in his crafty mind to run over the stander by the pond and trample him. He, poor fellow, missed the buck with both barrels. His roaring 10-gauge gun made enough noise to have stunned the buck; but the red-coated monarch serenely continued his march. All this happened near sundown, and it was the end of a perfectly doleful day. Prince laid the blame for the bull on me when he said, in mild rebuke: “Why, Cap’n, didn’t you put a true gunnerman in the critical place?”

Suddenly I heard a great bound in the bays. Prince’s voice rang out—but he stifled a second shout. A splendid buck had been roused.

The next day—the seventh straight that we had been hunting—it was an uncle of mine who got the shot. And this thing happened not a quarter of a mile from where the other business had come off. My uncle and I were hardly a hundred yards apart in the open, level, sunshiny pinewoods. Before us was a wide thicket of bays, about five feet high. The whole stretch covered about ten acres. Prince was riding through it, whistling on the hounds. Suddenly I heard a great bound in the bays. Prince’s voice rang out—but he stifled a second shout. A splendid buck had been roused. He made just about three bounds and then stopped. He knew very well that he was cornered, and he was evidently wondering how to cut the corners. The deer was broadside to my uncle, and only about fifty yards off. I saw him carefully level his gun. At the shot, the buck, tall antlers and all, collapsed under the bay-bushes.

Then the lucky hunter, though he is a good woodsman, did a wrong thing. Leaning his gun against a pine, he began to run forward toward his quarry, dragging out his hunting-knife as he ran. When he was within ten yards of the buck, the thing happened. The stunned stag (tall horns and all) leaped clear of danger, and away he went rocking through the pinelands. Believing that the wound might be fatal, we followed the buck a long way. Finally, meeting a woodsman who declared that the buck had passed him, “running like the wind,” we abandoned the chase. Buckshot bad probably struck the animal on the spine, at the base of the skull, or on a horn. Perhaps the buck simply dodged under cover at the shot; I have known a deer so to sink into tall broom sedge.

That night our hunting party broke up. Only Prince and I were left on the plantation. Before we parted that evening I said: “You and I are going out tomorrow. And we’ll take one hound. We’ll walk it.”

The next day, to our astonishment, we found a light snow on the ground—a rare phenomenon in the Carolina woods. We knew that it would hardly last for the day; but it might help us for a while.

In the first thicket that we walked through a buck-fawn came my way. He was a handsome little fellow, dark in color and chunky in build. It’s possible to distinguish the sex of a fawn even when the little creature is on the fly, for the doe invariably has a longer and sharper head and gives evidences of a slenderer, more delicate build. I would revisit him when he had something manly on his head.

Prince and I next circled Fawn Pond, a peculiar pond fringed by bays. Our hound seemed to think that somebody was at home here. And we did see tracks in the snow that entered the thicket; however, on the farther side we discerned them departing. But they looked so big and so fresh that we decided to follow them. Though the snow was melting fast, I thought the tracks looked as if two bucks had made them. Deer in our part of Carolina are so unused to snow that its presence makes them very uncomfortable, and they do much wandering about in daylight when it’s on the ground.

Distant from Fawn Pond a quarter of a mile through the open woods was Black Tongue Branch, a splendid thicket, so named because once there had been found on its borders a great buck that had died of that plague of the deer family—the black tongue, or anthrax. Deciding to stay on the windward (for a roused deer loves to run up the wind) I sent Prince down to the borders of the branch, telling him to cross it, when together the two of us would flank it out.

The tracks of the deer seemed to lead toward Black Tongue, but we lost them before we came to the place itself. While I waited for Prince and the leashed hound to cross the end of the narrow thicket, I sat on a pine log and wondered whether our luck that day was to change. Suddenly, from the green edges of the bay, I was aware of Prince beckoning violently for me to come to him. I sprang up. But we were too slow. From a deep head of bays and myrtles, not twenty steps from where he was standing, out there rocked, into the open woods, as splendid a buck as it has ever been my fortune to see.

He had no sooner cleared the bushes than his companion, a creature fit to be his mate, followed him. They were two old comrades of many a danger. Their haunches looked as broad as the tops of hogsheads. Their flags were spectacular. They were just about two hundred yards from me, and, of course, out of gunshot. Had I been with Prince at that moment (as I had been up to that fatal time) I would have had a grand chance—a chance such as does not come even to a hardened hunter more than a few times in a hundred years or so. The bucks held a course straight away from me; and their pace was leisurely. I watched them for half a mile, speechless, and with my heart pretty nearly broken. As for Prince, when I came up to him I found him unnerved.

“Cap’n, if you had been where I been just now!” was all he could say.

From the direction that the two great animals had taken, Prince and I thought that we knew just where they were going. Telling him to hold the hound for about fifteen minutes, I took a long circle in the woods, passing several fine thickets where the old boys might well have paused, and came at last to a famous stand on a sandy road. Soon I heard the lone hound open on the track, and you can imagine how eagerly I awaited the coming of what was before him. The dog came straight for me, but when he broke through the bays he was alone. The deer had gone on. It was not hard to find where they had crossed the road, ten yards from where I had been standing. From the way they were running they were not in the least worried. And from that crossing on they had a right not to be, for beyond the old road lay a wild region of swamp and morass into which the hunter can with no wisdom or profit go.

I did not stop the dog, deciding that by mere chance the bucks might, if run right, dodge back and forth and so give me the chance for which I was looking. The old hound did his best, and the wary old antlered creatures, never pushing hard, did some cunning dodging before him. Once more I saw them, far off through the woodlands, but a glimpse was all the comfort afforded me. After a two-hour chase the hound gave them up. Prince and I had to confess that we had been outwitted, and in a crestfallen mood we quitted the hunt for the day.

I felt that we would have to make good, or else be elected to the Has Beens’ Club.

The next day was my last at home, and every hunter is surely familiar with the feeling of a man who, up until the last day, has not brought his game to bag. I felt that we would have to make good, or else be elected to the Has Beens’ Club. I told Prince as much, and he promised to be on hand at daybreak.

I was awakened before dawn by the sound of a steady winter rain softly roaring on the old shingle roof. It was discouraging, but I did not forget that the rain ushered in my last day. By the time I was dressed Prince had come up. He was wet and cold. He reported that the wind was blowing from the northeast. Conditions were anything but promising. However, we had hot coffee, corncakes deftly turned by Prince, and a cheering smoke. After such re-enforcement, weather can be hanged. By the time that the dim day had broadened, we ventured forth into the stormy woods, where the tall pines were rocking continuously, and where the rain seemed to find us, however we tried to keep to leeward of every object. The two dogs that we brought were wet and discouraged. Their heads, I knew, were full of happy visions of the cheerful plantation fireside they had left. Besides, it was by no means their last day, and their spirit was lacking in all elements of enthusiasm. After about three drives, when Prince and I were quite soaked through, and were beginning to shiver, despite precautions that we took (“taking a precaution” in the South means only one thing), I said: “Now, Hunterman, this next drive is our last. We’ll try the Little Corner, and hope for the best.”

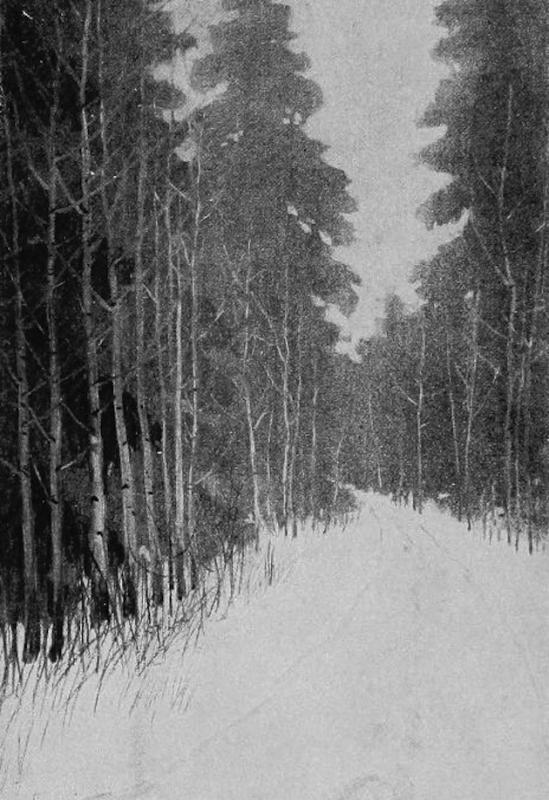

Two miles through the rainy woods I plodded to take up my stand. All that time Prince waited, his back against a pine, and with the sharp, cold raindrops searching him out. The wind made the pines rock and sigh. Even if the dogs were in full cry, I thought, I could never hear them coming. At last I reached my stand. A lonely place it was, four miles from home, and in a region of virgin forest. So much of the woodland looked just alike that it hardly seemed reasonable to believe that a deer, jumped two miles back in a thicket, would run for this particular place. But men who know deer-nature know what a deer will do. I backed up against an old sweet-gum tree, waiting in that solitary, almost savage place. I thought that in about a half hour Prince, bedraggled and weary, would come into sight, and that then we would go sloshing home through the drizzle.

But wonderful things happen to men in the woods. Hardly had I leaned against the big tree for shelter when, far off, in a momentary lulling of the wind, I thought I heard the voice of a hound. One of our hounds had a deep bass voice, and it was this that I heard. Sweet music it was to my ears, you can well believe! From where I was standing I could see a good half-mile toward the thickets whence had come the hound’s mellow, rain-softened note. And now, as I looked searchingly in that direction, I saw the deer, heading my way, and coming at a breakneck pace. At that distance, I took the fugitive for a doe. It was running desperately, head low, and lithe legs eating up the pineland spaces. If it kept its course, it would pass fifty yards to the left of me. I turned and ran low until I thought I would be directly in the deer’s path. I was in a slight hollow, and the easy rise of ground ahead of me hid the oncoming racer. I fully expected a big doe to bound over the rise, and to run slightly on my left. But it was not so.

Hardly had I reached my new stand when over the gentle swell of ground, grown in low broom grass, there came a mighty rack of horns, forty yards away to my right. Then the whole buck came full into view. There were a good many fallen logs just there, and these he was maneuvering with a certainty and a grace and a strength that it was a sight to behold. But I was there for more than just “for to admire.”

As he was clearing a high obstruction, I gave him the right barrel. I distinctly saw buckshot strike him high up—too high. He never winced or broke his stride. Throwing the gun for his shoulder, I fired. This brought him down—but by no means headlong, though, as I afterwards ascertained, twelve buckshots from the choke barrel had gone home. The buck seemed crouching on the ground, his grand crowned head held high, and never in wild nature have I seen a more anciently crafty expression than that on his face. I think he had not seen me before I shot; and even now he turned his head warily from side to side, his mighty horns rocking with the motion. He was looking for his enemy. I have had a good many experiences with the behavior of wounded bucks; therefore I reloaded my gun, and with some circumspection approached the fallen monarch. But my caution was needless. The old chieftain’s last race was over. By the time I reached him, that proud head was lowered, and the fight was done.

Mingled were my feelings as I stood looking down on that perfect specimen of the deer family. He was in his full prime. Though somewhat lean and rangy because this was toward the close of the mating season, his condition was splendid. The hair on his neck and about the back of his haunches was thick and long and dark. His hoofs were very large, but as yet unbroken. His antlers were, considering all points of excellence, very fine. They bore ten points.

My short reverie was interrupted by the clamorous arrival of the two hounds. These I caught and tied up. Looking back toward the drive, I saw Prince coming, running full speed. The dogs had not had much on him in the race. When he came up and saw what had happened, wide was the happy smile that broke like dawn on his dusky face.

“Did you see him in the drive, Prince?” I asked. “He surely is a beauty.”

“See him?” he said in joyous excitement. “Cap’n, that old thing been lying so close that when he jumped up he threw sand in my eye. I reached for the big tail to catch him. But I know,” he ended, “that somebody else been waiting to catch him.”

I sent Prince home for a horse on which we could get the buck out of the woods. While he was gone, I had a good chance to look over the prone monarch. He satisfied me. And the chief element in that satisfaction was the feeling that, after weary days, and after adverse experiences, the great chance will come. For my part, that Christmas hunt taught me that it is worthwhile to spend some empty days for a day brimmed with sport. And one of the lasting memories of my life is the recollection of that cold, rainy day in the Southern pinelands—my last day for that hunting trip—and my best.

Be sure to sign up for our daily newsletter to get the latest from Sporting Classics straight to your inbox.

This story originally appeared in Field & Stream, January 1920. Cover image from the issue. Illustrations from In Berkshire Fields by Walter Prichard Eaton, published 1920. All materials made available by the Internet Archive.