We rejoice through Sheldon’s reminders in knowledge that so long as sportsmen can dream of field and stream there will be tales to enchant and endure.

As this column is being written, we find ourselves in a situation where ample doses of serenity, common sense and mental comfort are in great demand. We are a nation beset by a bad case of what folks in my native Appalachian high country describe as the mollygrubs. This wonderfully expressive word’s precise meaning can be elusive, but in essence it is a virulent blend of cabin fever, blues, being down in the dumps and flat-out depression. Yet for sportsmen, there’s a cure for mollygrubs in the form of uplifting chronicles of adventures astream and afield. Short of actually being on the scene, few aspects of the outdoor life offer more delight than the pages of a good book. A talented author can produce paroxysms of laughter, set tear ducts in high gear, have your stomach growling with descriptions of grand game feasts or otherwise bring vicarious pleasures that brighten your day and lighten your way. A good book is, in short, a boon companion offering escape and enjoyment.

We’ve had gifted writers aplenty in this regard. A personal all-time favorite, never mind my general preference for scribes from the Southern heartland, is about as definitively Yankee as it is possible to be. Harold Pearl Sheldon (1887-1951) was a staunch son of the Vermont soil who wrote three marvelous books and scores of stories for outdoor magazines set squarely in the land he knew best. Born near the small town of Fair Haven, he grew up on his family’s place known as Valley Farm. The names of both village and farm evoke an aura of comfort and peace, and precisely the same is true of Sheldon’s writings.

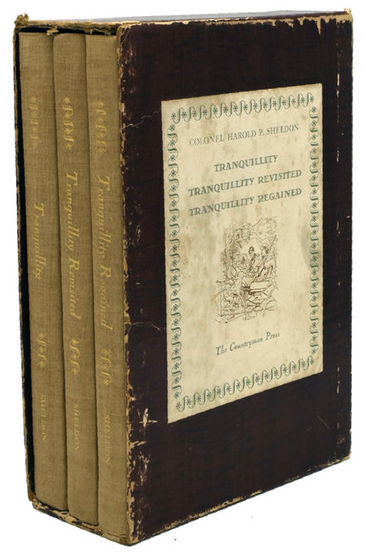

Sheldon’s Tranquility in a boxed set sold for $85 in a 2019 online auction. Prices vary.

The foundation of Sheldon’s legacy lies in three books often known as the Tranquility trilogy. They reflect a charmed life—a boyhood hallmarked by closeness to the earth, solid grounding in sport from a young age, parents with a deep feel for how the natural world can shape life and give it savor and, above all, appreciation of blessings bestowed by the hunting and fishing life. The setting for his books is mythical Tranquility Village, closely modeled on Fair Haven. Reading Tranquility, Tranquility Revisited and Tranquility Regained brings a sense of peace and quietude that leaves no doubt that choosing the name Tranquility was a felicitous one. In the pages of the books you will find wit and whimsy, gladness tinctured by sadness, hints of magic and occasional elements of the tragic. Some of Sheldon’s characters become old, treasured friends similar to those peopling Gordon MacQuarrie’s Old Duck Hunters stories or Corey Ford’s Lower Forty adventures.

After completing high school, Sheldon matriculated at both George Washington and Georgetown universities before joining the Army at the age of 23. Several years later, in the latter stages of World War I, he served on the Western Front as a member of the 102nd Machine Gun Battalion of the Yankee Division. He was seriously wounded during the fierce Meuse-Argonne offensive, an important part of the final Allied thrust to victory. By war’s end Sheldon had risen from private to the rank of captain. He continued active Army service briefly after the Treaty of Versailles, serving as commandant at Fort Ethan Allen in his native Vermont before subsequently being commissioned lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserves. He clearly took considerable pride in his service and his byline in stories and on the title pages of his books is always Colonel Harold P. Sheldon.

Once he left full-time service in 1921, the remainder of his career centered on the outdoors. Sheldon first served for a time as an editor in the public information division of Vermont’s Department of Agriculture before becoming Fish and Game Commissioner for the state, where he gained invaluable training for his next position. In 1926 he became chief U. S. Game Warden and head of the Department of Biological Survey’s Division of Game and Bird Conservation (subsequently known as the Department of the Interior’s U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Sheldon worked there until his retirement in 1943.

Title page of the Countryman Press edition

While it is the Tranquility trilogy many readers will already recognize, before turning to those books at least passing mention of Sheldon’s other writings is merited. Thanks to his public service, Sheldon knew most of the era’s major writers and leading voices in conservation. That shows in various ways including a foreword to Horatio Bigelow’s Gunnerman, an introduction to Nash Buckingham’s De Shootinest Gent’man and Other Tales and an opening essay, “The Saga of Bo Whoop,” to Mr. Buck’s Hallowed Years. These endeavors likely came with Eugene Connett, scion of Derrydale Press and publisher of the originals of the first two books, acting as an intermediary. A recognized firearms expert, Sheldon wrote the “Guns and Game” column first for The Sportsman magazine and subsequently a similar column for others. He was a regular contributor to Country Life, Outdoors Magazine, Outdoor America, Forest & Stream, Outdoor Life, Field & Stream, American Rifleman, National Sportsman and Outing. Indeed, he was sufficiently prolific that there’s likely a “Lost Classics of Colonel Harold Sheldon” book awaiting some enterprising researcher.

Dust jacket of the A.S. Barnes & Company re-issue

Not all critics have been enamored of Sheldon’s contributions to magazines. George Bird Evans, who could be simultaneously acute, astute and acerbic, devotes essays to Sheldon in Men Who Shot and George Bird Evans Introduces criticizing him for some of his magazine endeavors, saying that in “writing for a price, Sheldon paid the price of writing what would sell.” There is unquestionably an element of truth in this pronouncement, yet precisely the same criticism could be leveled at virtually any outdoor writer of yesteryear or today, be it Sheldon, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Robert Ruark or Evans himself. After all, most sporting scribes are trying to eke out a living or supplement meager incomes; only the privileged few enjoy the luxury of not worrying about economic matters.

Sheldon needed money and he wrote for money, especially in magazines. For my money though, this in no way affected quality. Still, it was in books he shone brightest. There he could transcend the constraints of word counts, the kind of subject specificity columns demand and the inherent narrowness linked to short pieces. As is the case with virtually all outdoor writers of note, it is through his books, what Nash Buckingham styled “those wonderful Tranquility stories,” that posterity applauds him.

The first of these, Tranquility, appeared in 1936 under the famed Derrydale Press imprint. Tranquility Revisited followed from the same publisher in 1940 and the 1945 appearance of Tranquility Regained, this time from Countryman Press, completed the trilogy. All initially came in limited editions, with the first being 950 numbered copies, the second 485 numbered copies and the third a much larger edition of 5,000 copies. The latter was accompanied by Countryman Press reprints, cheaply done and in a similar press run, of the first two books. Later, Ralf W. Coykendall, Jr. edited The Tranquility Stories (Winchester Press, 1974), and his effort includes a useful biographical profile of Sheldon.

Since then, there have been additional reprints. In 1986 Willow Creek Press offered a boxed set, without dust jackets, of the trilogy. The reincarnation of Derrydale Press brought the first of the trilogy anew in 1991 and Premier Press offered it (with a new Introduction by Jared Lobdell) in 1995. Earlier, in 1992, the latter publisher also brought out Tranquility Revisited (with a new Introduction by the present writer). All were in limited editions. Finally, in 2013, A. S. Barnes did a slipcased edition of the three volumes. Quite possibly there are other reprints, but it should be abundantly obvious that Sheldon’s work has been of an enduring nature and in many cases is relatively inexpensive. On the other hand, if you want a nice copy of the original Derrydale Press version of Tranquility Revisited be prepared to lay out several hundred dollars.

Woodcock in New Brunswick by A. Lassell Ripley, watercolor, 20 x 29 3/4 inches, 1947. Several Ripley works were included in the Premier Collection reprint of the book.

Sheldon lived, hunted, fished and walked through a world we have in no small degree lost. Yet the strength of character, simple humanity, transparent honesty and milk of human kindness found in his pages still hold sway among devoted sportsmen and in rural settings not only in New England but across the country. To share a crisp October day with Sheldon’s Tranquility characters, punctuated by fine dog work and perhaps a perfect left-and-right on a brace of birds, is to be filled with reverence for sport’s myriad deeper meanings. To visit his quasi-fiction Tranquility is to know life’s rhythms as revealed in sport and be enchanted by the wonders of the wild. Best of all, in the Tranquility tales you reach a state deserving of the titles. A mess of mollygrubs gives way to a tranquil time as we rejoice through Sheldon’s reminders in knowledge that so long as sportsmen can dream of field and stream there will be tales to enchant and endure.

Addendum

Normally mea culpas are tough, but not in this case. A couple of columns back, while reviewing a new collection of Gordon MacQuarrie stories, I commented that full-time newspaper outdoor writers were extinct. It turns out that while they are unquestionably an endangered species, there are still a handful of newspapers with staff positions devoted exclusively to outdoors coverage. One of them is MacQuarrie’s Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, where from his initial hiring in 1936 to the present day there has always been a full-time outdoors editor. Others include the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Duluth News Tribune and Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Their readers should realize they are blessed and perhaps give an approving nod to the respective publishers for clinging to an important part of our sporting literary heritage.

This book is a collection of outdoor stories wrapped in the human condition. They were written with an eye toward honesty and cynicism. They will make you laugh out loud, and you will want to carry them with you wherever you go. If this book goes missing, it’s a sure thing that, when you do find it, it will be in the possession of a member of your household, regardless of their interest in casting a fly. The stories cover the gamut from a fishing trip to northern Canada to a little stream that was actually better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek along railroad tracks during a cold, dark, and dreary February and many more. Buy Now

This book is a collection of outdoor stories wrapped in the human condition. They were written with an eye toward honesty and cynicism. They will make you laugh out loud, and you will want to carry them with you wherever you go. If this book goes missing, it’s a sure thing that, when you do find it, it will be in the possession of a member of your household, regardless of their interest in casting a fly. The stories cover the gamut from a fishing trip to northern Canada to a little stream that was actually better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek along railroad tracks during a cold, dark, and dreary February and many more. Buy Now