Although the skies had cleared, high water in the wake of the previous day’s rain eliminated any possibility of sight-casting to individual fish that April morning. But rain is trophic to steelhead, drawing them upriver from the sea and activating the switch that transforms them from travelers poking their way upstream into aggressive gamefish. Steelhead fishing always involves an element of uncertainty, but I expected good things that morning; the stream wasted little time fulfilling its promise.

Most stretches of Southeast Alaska’s small coastal streams are easy to wade, but in anticipation of bright fish inbound from the sea, I’d picked a rare exception that day, close enough to salt water to ensure that the steelhead would still be vigorous before they started to darken prior to spawning.

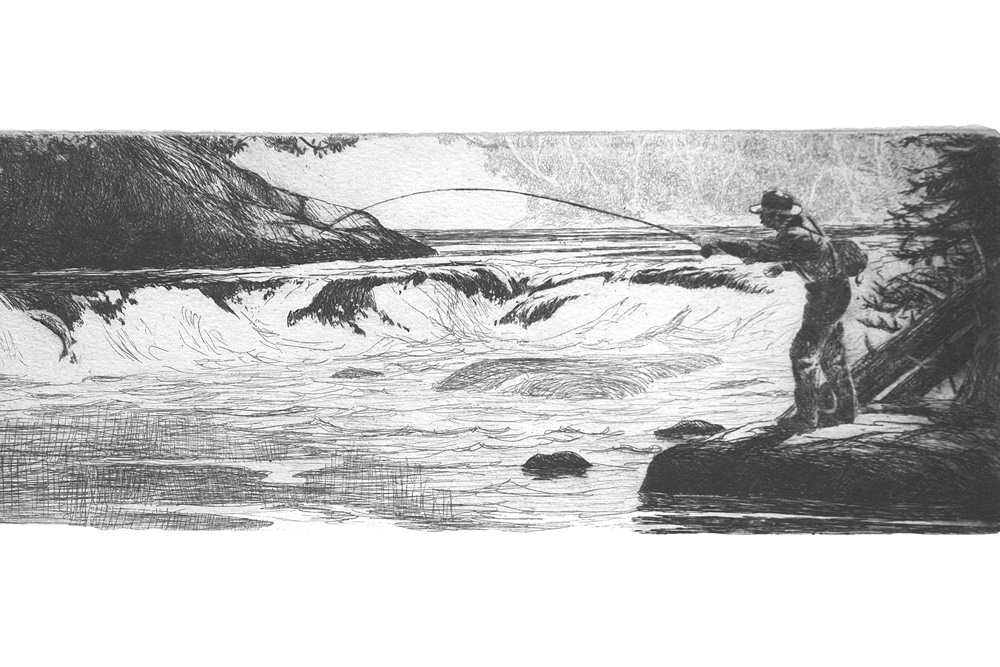

After exiting a lake and rambling across a delightful mile of pools and frog water, the stream I’d chosen to fish bottlenecked as it roared through a tight canyon bordered by rocks, deadfalls, and brush. It’s a challenge just to reach the water even when it’s low, much less stay upright in the current long enough to fish it. Now the recent rains had made the current even higher and faster than usual. But after scrambling down the canyon walls and easing into position behind a midstream boulder, I let a backhand rollcast unfold—and promptly hung my weighted nymph on a snag.

Or so it seemed. Fortunately, 50 years of experience had taught me to treat any hesitation in my fly line as a steelhead until proven otherwise. My reflexive strip-set came up hard against something soft but unyielding—a submerged tree limb in all probability. Then my line began hissing downstream ahead of a rooster-tail of spray, leaving me staring at a yard of airborne, silvery fish and my disappearing backing. The vigor of the steelhead and the force of the current behind it rendered my position hopeless. I torqued my drag past redline and stretched my rod tip high as the fish ran a slalom course between the rocks. Then it was over.

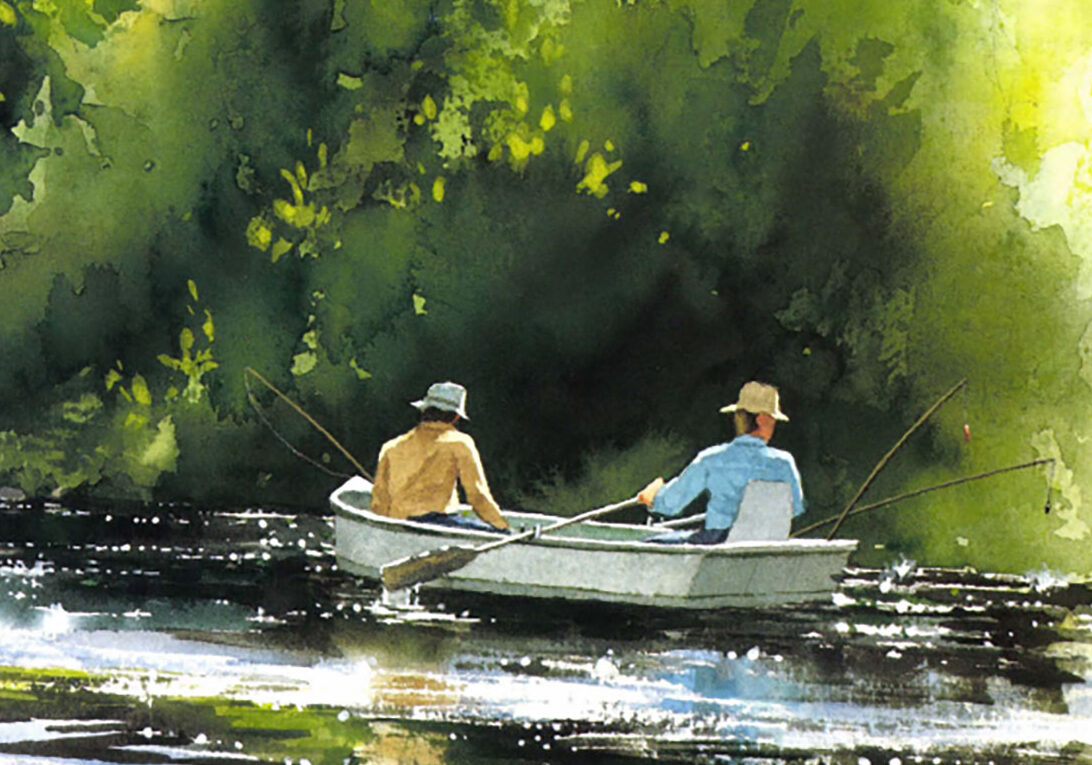

Many Southeast Alaska steelhead streams are a bit too small for Spey rods—but not all.

Both the steelhead and the Atlantic salmon have been described as the fish of a thousand casts. While I lack experience with the latter, I’ve always considered that ratio pessimistic with regard to the steelhead, perhaps because I’ve organized my life to keep me close to prime water and perhaps because I’ve actually learned something about steelhead over the years. I grew up fishing fanatically for steelhead in Washington State but found an even more target-rich environment when I moved to Alaska. Even I can learn a thing or two after 50 years of effort.

The 1,000-to-1 ratio certainly didn’t hold up that morning—I brought a half-dozen big chromers to hand and not even Alaska’s long spring days allow enough time for that many hook-ups at a thousand casts per fish. Not every day of Alaska steelhead fishing produces action like that, but enough of them do to keep hardcore fanatics coming back.

Anglers in Alaska should always be prepared for bad weather, even under blue skies.

The Southeastern Alaska Panhandle lies in the heart of the world’s largest temperate rainforest, and the trees define the ambience better than words ever could: Douglas fir, western hemlock, and Sitka spruce tower so high their tops often disappear in the mist overhead. In places where true old-growth still stands, the trees’ shade chokes out the tenacious brush that lines the streams, leaving a lush, magical carpet of ferns and mosses in its place. To enter these woods at the beginning of a hike to the stream feels like stepping into a cathedral dedicated to the worship of wild places.

Of course Southeast—as it’s known to Alaskans—isn’t always a rose garden. Outside the big woods where the canopy chokes out the undergrowth, alders, devil’s club, and slash left behind by a century of logging can make foot travel a challenge, if not a nightmare. Gaining access by boat involves complex inshore navigation and raging tides. The bush flying is some of Alaska’s trickiest. And getting by in the rainforest means dealing, logically enough, with lots of rainfall—more than 200 inches per year in some places.

This steelhead struck a single egg imitation drifted like a nymph.

It would take exceptional fish to motivate an angler to endure all that, but Southeast has them in variety as well as abundance. Five species of salmon for those who enjoy challenge on the fly rod. Halibut for those anglers intrigued by the idea of landing fish that can weigh more than they do and filling the freezer with one swing of the gaff. And then there are the steelhead.

Biologically, steelhead are nothing more than huge rainbow trout designed to out-migrate from their natal streams to the sea. In the Lower 48, many of the historic runs have been extirpated and replaced by insipid hatchery-reared imitations, but in Alaska the steelhead are as wild as ever. Having chased all manner of gamefish all over the world with my fly rod, I can say without hesitation that nothing matches them for challenge and intrigue. They are the reason I live in Southeast Alaska today, and the privilege of fishing for them justifies every bit of the inconvenience outlined earlier.

A little current and a lot of fish make for a long fight.

Alaska steelhead return to fresh water both spring and fall. Autumn runs predominate farther north in their range throughout the state, on Kodiak Island, and on the mainland from the Kenai to the Alaska Peninsula.

While many Southeast waters host fall runs, I do most of my fishing during the spring—late March through early May—for reasons beyond the larger numbers of fish present then. The days are longer, the weather more likely to be pleasant. Of particular importance, spring is the season when I need to go fishing. Others who have endured long winters in Alaska or Montana or anywhere else will understand.

The where is a broader question than the when. The good news: Southeast contains a lot of prime steelhead water. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game maintains a list of streams known to support steelhead runs, and that catalog includes more water than most of us could fish in a lifetime. Some of my favorites aren’t even on the list. It’s hard to find a stream in the Panhandle that doesn’t host steelhead, although in some of the smaller drainages the annual return may be fewer than 50 fish.

Chest waders, woolens, fingerless gloves, and a box of flies—all essentials on an Alaskan steelhead trip.

But some hold a lot more, and the Situk, near Yakutat, tops them all both in terms of fish numbers and angler popularity. Other perennial favorites include the Naha near Ketchikan and the Karta on Prince of Wales Island. Many steelhead streams are so remote they require a major expedition to reach, while others, such as Ketchikan Creek, run right through the middle of town.

Southeast can be a challenging destination for do-it-yourself anglers. The easiest, most efficient way to sample this fishery is by staying at one of the area’s numerous full-service angling lodges. During the summer salmon and halibut seasons, most of these operations focus on saltwater fishing with conventional tackle, but some are located near good steelhead water and know how to help their guests get flies in front of the fish.

The visitor who wants to fly to Alaska, rent a car, and go steelhead fishing will have an easier time of it on Kodiak Island or the Kenai Peninsula during the fall. However, anglers who enjoy adventure, wish to economize, or want both certainly have options in Southeast.

Many of the region’s population centers (such as they are—this is Alaska) lie just a short bush-flight away from good steelhead streams inaccessible by road. Flight services in Ketchikan, Sitka, and Juneau—among others—can arrange reasonably priced day trips (weather permitting, as always). At a bit more cost, unguided mothership operations offer a great way to experience the area’s maritime wilderness and reach a variety of water on one trip.

A hard-fought battle ends.

The best compromise between wilderness and price may come by renting a forest service cabin at nominal cost. A number of these cabins are located right on good steelhead streams. Almost all will require at least a short trip by boat or floatplane, but that’s the reality of getting anywhere in an area that has no contiguous road system. Reservations are required and cabins located on the best-known streams book up fast, so plan ahead.

The year after my adventure in the canyon, two days of drizzle matured into a downpour, providing my philosophical attitude toward coastal Alaska weather with its sternest test of the season. My skin felt damp from the neck down despite my raingear. Above the neck I’d given up, as water dripping off my hat sought and found new routes down my collar.

A lazy cast away on the opposite bank, my wife, Lori, looked like a wet, blonde grizzly bear as she poked through her fly box looking for a heavier streamer. I wasn’t even wondering about when to retreat, since I knew the water would make that decision for us. The way it was crawling up the stick I’d planted in the gravel on the bank behind me, our window of opportunity to fish the stream would close in an hour or two, no matter how we felt about staying.

I swung an Egg-Sucking Leech across the current below me. This pattern, which resembles nothing in nature, has nonetheless accounted for more anadromous fish than any other in Alaska. While the rising water was pushing the fly up out of the zone as it quartered past me, I hoped the changing conditions would motivate a steelhead to leave its lie next to the bottom and smack the fly.

And then one did. In contrast to the subtle takes a dead-drifted nymph can provoke, a steelhead seldom leaves much doubt when it hits a swinging streamer. The strike was a real wristbreaker, and the strip-set from my line hand was probably unnecessary. But my father taught me decades ago that the steelhead should really be named the “steelmouth,” and I popped the fish with as much force as I thought the tippet could handle.

Steelhead streams are numerous in Southeast Alaska.

Over the previous two days Lori and I had hooked a grand total of one fish between us. (Full disclosure—she hooked it, and I watched the show.) The point is that encounters with fly-rod steelhead are not randomly distributed, no matter what the location or the experience level of the angler. Sometime is just doesn’t happen, and sometimes it does. Becoming a real steelhead angler requires developing the ability to enjoy the days when there’s nothing to talk about but the current.

But patience in sufficient quantities always leads to reward, as it did that rainy day. I’d no sooner set off slipping and sliding downstream in pursuit of that first fish when a whoop from Lori rose above the clatter of the rain against my jacket. I never did catch up with my fish, but hers chose to circle the pool in front of her at high speed rather than run for the sea.

By the time I slogged back up the bank trailing a lifeless fly line, she was bringing her fish to bay in the shallows. Since we needed to be on the same side of the stream, I found a wading stick and made the increasingly difficult crossing.

We hooked four more fish before high water sent us scrambling downstream toward the skiff and what I hoped wouldn’t be a mental error about the timing of the falling tide. I didn’t feel like dragging the skiff across half a mile of beach.

Coastal Alaska isn’t for every angler. There are easier places to catch steelhead, which is really to say there are less difficult places to catch steelhead. But the opportunity to pursue the world’s greatest gamefish in a splendid maritime wilderness is special in itself—rain, alders, thousand casts, and all.

Renowned fishing writer Paul Quinnett and whimsical artist Deanna Camp team up to show you the fish you’ll forever want to catch, because you’ll almost certainly never catch one. Still, hope springs eternal in the breast of every angler, which is really the whole point. The 120-page features both full-color paintings and photographs. Buy Now