Young men unthinkingly take chances by driving fast cars and chasing fast women because they believe they are immortal, that they will never die. More mature men choose to openly embrace danger because they know they are not and most surely will.

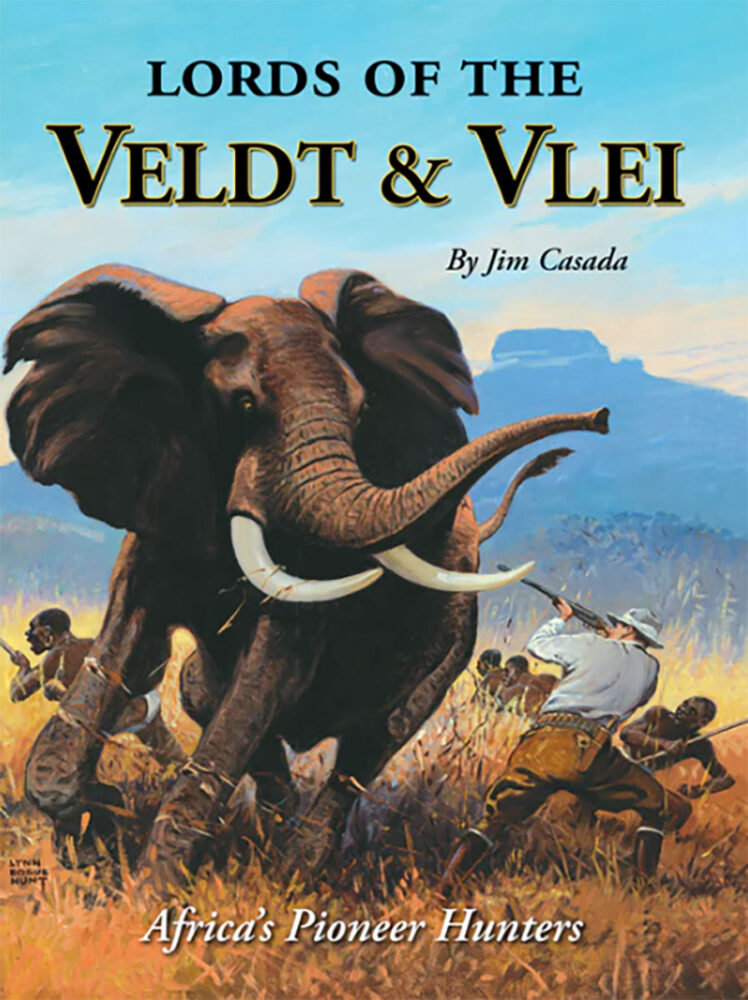

Hunting an animal that can kill you as easily as swatting a fly really doesn’t make much sense on a purely intellectual basis. It is more on emotional or philosophical terms that men pursue close encounters with death. To place oneself in harm’s way, to stalk mere yards or even feet away from a quick and horrible demise by way of fang and claw attached to 500 pounds of angry feline; wickedly hooked horns driven by nearly a ton of vindictive rage; or six-foot spears of ivory tusk jutting from 10,000 pounds of cunning, crushing death is for some an inevitable culmination of a hunting life’s dreams.

To take rifle in hand and face magnificent beasts honed by eons of evolution, to best not only those animals on their own terms and ground, but to conquer one’s personal frailties and fears, is not a decision to be taken lightly. Nor is it for everyone. It is, however, a chance to walk on the razor edge of what makes us hunters.

Botswana PH Johan Calitz runs one of the largest and best safari operations in Africa.

The new-penny copper glow of daybreak over the Okavango Delta was still just a hint in the east as cape turtle doves, red-billed francolins and fork-tailed drongos erupted into their morning chorus around our tent. I had been awake for at least two hours anyway. My time had come to experience a hunter’s life to its fullest, to put myself in the path of the largest land animal on Earth. I was wide awake. Even at age 52 and a hunter for more than forty of those years, I was still unable to believe it. I was an elephant hunter.

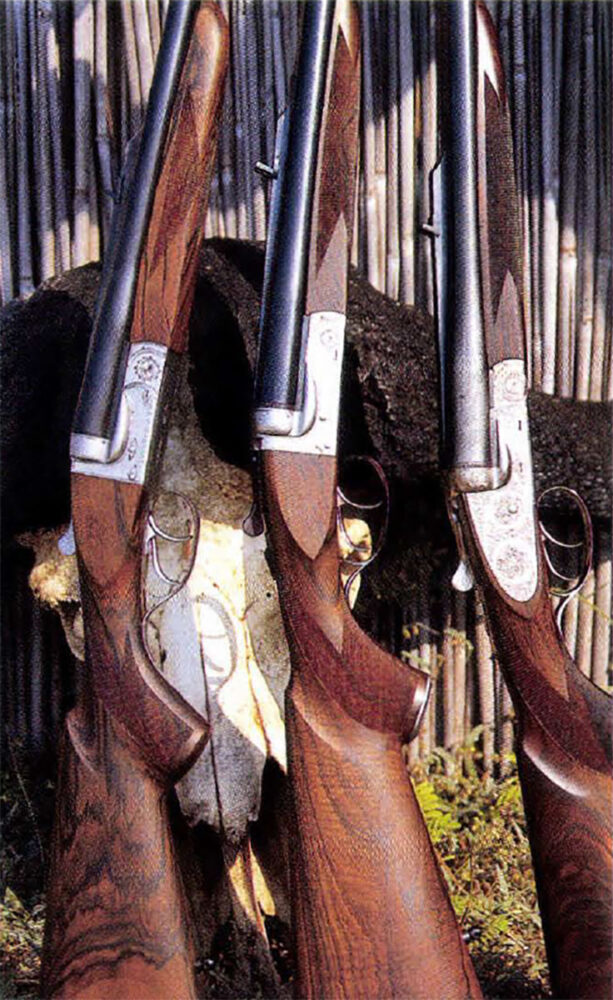

Butch Searcy, builder of high-quality double rifles in Boron, California, was beginning to stir in the other bunk. He and I had met at a sports show several years ago and soon became friends. If I were to shoot an elephant, I wanted it to be up-close with one of Butch’s doubles. Two years previously I had traded several of my bolt-actions for one of his accurate creations in the traditional 470 Nitro Express caliber. It was through our friendship and Butch’s close relationship with professional hunter Johan Calitz that we were now ensconced in Johan’s Ivory Camp in the middle of northern Botswana.

Johan owns one of the largest and best-run safari operations in all of Africa, with nine different camps. A tough, likable and infinitely honest man of Afrikanner descent, he is undoubtedly the most knowledgeable PH I’ve ever known. After a week of hunting with him and standing together, shoulder-to-shoulder in thigh-deep water, the long grass three feet above our heads, as we sorted out a wounded and very angry Cape buffalo, I now had grown to consider Johan as a valued and trusted friend.

Going on this trip had been a unique decision, unlike any I’d ever faced in my outdoor experience — to resolve in my own mind if I even wanted to hunt an elephant. I had never given it serious consideration until I met Butch and Johan. But when one Johan’s clients cancelled unexpectedly, the opportunity became a reality.

My quandary wasn’t that I thought elephant hunting was wrong or immoral. Those are the overly emotional sentiments of the uniformed. When I told a friend’s wife at dinner one night that I was going elephant hunting, she reacted indignantly, “Why would you want to shoot an elephant? Do they still let people do that?”

I explained that elephants are thriving in countries where sport hunting is an effective management tool, the best means of keeping their numbers in line with their habitat. Because a large portion of the monies spent on government licenses and trophy fees are funneled directly into the African commonalities where the elephants are shot, local residents benefit from new medical clinics, schools, medicine and oilier services. These monies also pay for anti-poaching measures, further ensuring the safety of the herds. The elephants win and poachers, the real culprits in the depravation of elephant numbers, lose. When Botswana reopened elephant hunting in 1996 after a 10-year hiatus, there were about 80,000 in the country. Now, estimates range from 120,000-150,000. This year about 150trophy bulls were killed — only one in a thousand. Taking one old bull, past his breeding prime, can ultimately save the lives of a hundred. Or a thousand. In addition, all of the meat is used by the locals. Nothing goes to waste.

But was it for me? Over the years several PHs had told me that unequivocally, the African elephant was the grandest game of all. When I asked Johan, his answer was immediate. “Cape buffalo are fun to fool around with but elephant hunting is the ultimate. That’s because they are the biggest, the most intimidating, the smartest and most cunning and the most dangerous and hard to stop when wounded.” That was enough for me.

Botswana, one of the least populated countries in the world, is an outstanding safari destination. The southwestern third of the country is covered by the vast Kalahari Desert, and to the northeast, the Chobe area ranges from bush to mopane forest. Both have excellent hunting, but Botswana’s crown jewel is the Okavango Delta, a wilderness covering more than 7,000 square miles.

A wild-eyed and angry young elephant mock-charges the author.

Bordered by the Kalahari, the Okavango is a spectacular oasis of flooded grasslands, serpentine waterways and islands. Created by the Okavango River and its many tributaries, the crystal-clear water of the delta creates one of the most verdant areas on the planet. Its wildlife dazzles the visitor’s imagination with more than 160 species of mammals and a staggering 400 different varieties of birds.

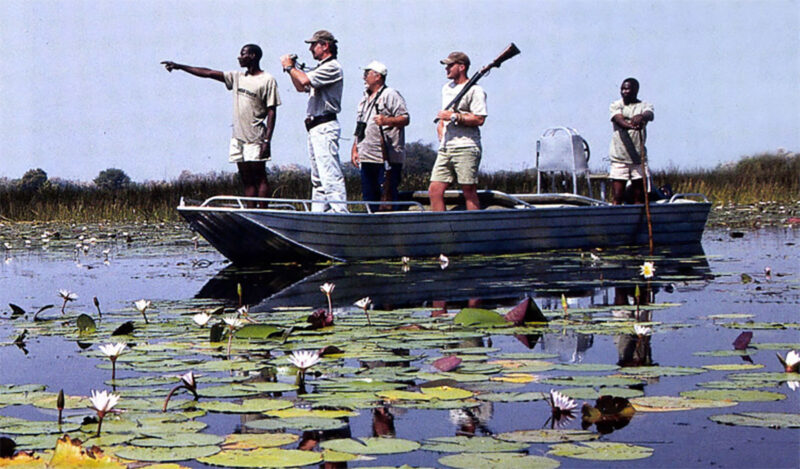

After breakfast each morning Johan, Butch and I boarded an aluminum boat with Olly and Dan, our Tswana trackers, and Active the local community’s game scout. Beginning in the morning when the air was cool and a light jacket felt good and throughout the sunbaked days, we motored the endless channels of the delta. Other days we bounced across huge tracks of countryside in the Land Cruiser. More miles of shoe-leather were expended following dusty elephant tracks and wading waist-deep water filled with saber-sharp marsh grass.

For seven days we hunted hard for the light trophy bull. In the mornings we looked for plains game and buffalo, but as the sun became hotter toward noon, we searched for the elephants that came to the main liver channels to drink a portion of the thirty gallons of water they require each day.

And indeed, we saw elephants. Many elephants. At least 20-30 bulls every day though none possessed the 60pounds of ivory per side that is the benchmark for Johan’s clients. Something in the mid-50s was starting to look good.

The huge bull, one of the largest elephants in Botswana, was in the beginning of his last decade of life. Having lived through fifty-two rainy and dry seasons, he had trekked great distances, migrating not only across much of the northern third of Botswana but also hundreds of miles in Zambia, Namibia and Zimbabwe. He had grown wise. He knew where the sweet grasses and tasty trees limbs grew, where he could find water even during the dry tim.es. In his earlier years, during his musth periods when breeding dominated his mind, he had known where to find the cow herds.

The old bull had returned tohis favorite palm plantation on a large island. He was there to gorge on the delicious nuts that f ell at his feet when he used his massive head or his thick, heavy tusks to shake the palm trees. Water to drink and mud to roll in were both nearby. His comrade, a mature but much younger bull, would keep him company and help watch for any signs of danger.

On the afternoon of our fifth day, we thought we had found our elephant. Olly, Dan and Active spotted him in a herd of nine bulls at least a half-mile inland from the river. We beached the boat, and the trackers ran ahead to judge the big bull. Soon they were back, describing his long, beautiful ivory. From their description of more than forty inches outside the lip and medium-heavy thickness, Johan thought the tusks would go in the high 50s, perhaps crowding 60 pounds per side. We immediately began our stalk. Evidently the elephants had already watered and were heading back into the bush to resume their 20 hours of feeding for the day.

Nearly an hour later we were close enough to hear them popping tree limbs as they fed. The one we wanted was right in the middle of the group, but as we crossed an opening a young bull spotted us, threw his ears out and raised his trunk. ‘We froze. In a few moments he seemed to calm down, and when the elephants began traveling again, we closed the gap.

Three models of superbly accurate Searcy double rifles were used on the hunt.

Stalking to within 60 yards of where they would all come out into an open plain, I readied myself for the shot. Johan and Butch would back me up. A bull walked out into the open. Not our guy. Then another and another. In single file, eight bulls strolled by, but not the one we wanted. When they were out of Sight, we doubled back but found nothing. The big bull had vanished. He had probably sensed something was wrong when the younger elephant raised his ears and trunk and had simply walked away. We never saw him again.

Two days later we drove to an immense palm plantation an hour and a half from camp that Johan knew to be a favorite feeding ground for elephants. With more and more bulls showing up each day in their spring migration from the Chobe area, we might get lucky.

On the way we spotted a large bull just emerging from the trees to water at a pan. He had short, thick ivory but moved back into the bush at the Sight of the truck. We jumped out and quickly closed to only twenty-five yards downwind of him. As the big bull walked into a clearing, we could see that he had one tusk of about 55 pounds, but the other side was badly broken. We reluctantly decided he wasn’t for us.

There were many elephants in the palms, their huge, gray shapes dotting the scene as they feasted on the golf ball-sized palm nuts. They had already destroyed at least a thousand acres of 30—50-foot mopane trees nearby, uprooting the trunks to reach the few juicy twigs at their tops.

We saw nothing with heavy ivory, although we looked over a middle-aged bull with extremely long but thin tusks. As we glassed him, a youngster about 15-years-old screamed his indignance at our intrusion, mock-charging to within 25 yards and flapping his ears. He stopped, then glared wildly at us before taking off at a fast lope, trumpeting all the way.

Then, after sighting more than two dozen elephants, we noticed a large bull far off from the others. As we approached to within a couple of hundred yards he moved deeper into the forest, but as he turned sideways, I got a glimpse of his tusks. They were thicker by far than any we had seen. I knew he was the one we had been looking for. Johan and the trackers agreed, and quietly motioned for us to ready our rifles.

As I buckled on my heavy cartridge belt and dropped two 470 solids into the chambers, I began to feel a tremendous pressure in my mind and indeed, within my soul, to do well. This couldn’t really be happening. I was going to shoot an elephant. I took a deep, mind-clearing breath as we walked toward where we had last seen the bull.

The old bull lost Sight of his younger companion, his second set of eyes, who always traveled with him. No matter, his own senses had never let him down. But he didn’t know there was a small, frail being, a man the same age as him, only a few hundred yards away. The man and several other humans were looking for him. Over the years the old matriarch of his herd had trained him to run away when he smelled such beings, that they were as much a part of the food chain, as much a part of the law of survival of the fittest, as the lion and buffalo. But no such dangerous stench reached the old elephant and besides, he had eating on his mind. There was much more food to consume this day and the nuts of the tall trees were very good.

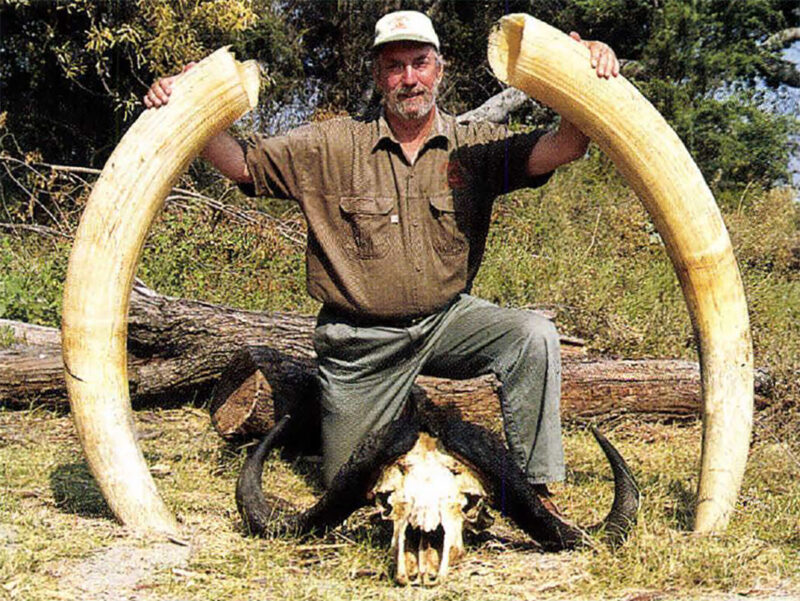

The author’s six-foot tusks weighed 74 and 73 pounds.

When the 470s clunked into the chambers of my rifle and we started out after the big bull, the same feeling hit me as when I had hunted buffalo earlier in the week and had approached close to other elephants. But it was a completely different sensation from anything I had felt on past hunts for deer, elk or plains game. Not only was there excitement, but also extreme apprehension.

We stalked closer and closer to the bull, which was ghosting though the forest only 35 yards away. Johan motioned for me to step up even with him and get ready to shoot. The bull’s tusks were heavy and long, one broken off just a few inches at its blunt tip. Easily weighing more than five tons, the elephant was as big as a house. A very large, powerful, intimidating house.

The bull suddenly stopped in a small clearing and looked our way. His tiny amber eyes seemed to recognize that something was wrong with the landscape. His giant head, 10 feet above us, turned in our direction; huge ears fanned out, straining for sound. His massive trunk, framed by tusks as big around as my leg, raised in defiance of any potential danger. The feeling in my gut and the taste in my mouth had a new flavor — the flavor of fear. The fear of the unknown. Of what was going to happen when I pulled the trigger. I raised the rifle and pushed off the safety. Wait until he turns,” Johan whispered. “Wait. Wait.”

The great head began to turn away. Hot, nervous, scalding sweat ran down my face and into my eyes. I began to take up the slack in the trigger.

He sensed rather than saw the forms to his left· The huge bull swung his head around to get a better look. Though his eyesight had never been that keen and was certainly not as good as it once was, the small and vaguely familiar shapes, both black and white, were very still. They didn’t seem, in their insignificant smallness, to pose any danger. Neither could he smell anything out of the ordinary. As he turned to leave, the old bull saw a flash erupt from one of the tiny forms and he stumbled, stunned. There was little pain, but now he realized they were a threat and fury engulfed him. Eyes blazing, he shook his head and flared his ears in anger as he took a step forward to crush out their very existence.

The big rifle kicked hard into my shoulder, but I never felt it. The bead of the front Sight had been right where I thought it was supposed to be for a well-placed shot. Micro-seconds later, as the rifle returned from recoil to rest on the target, my brain screamed that something was wrong. Very wrong! He hadn’t fallen!

It took only a couple of seconds before my second bullet and one from Johan’s rifle were on their way. But it was long enough for me to see the unmistakable look in the bull’s eyes, to fully comprehend that the first shot had had little effect other than to enrage the huge animal. It merely set into motion his intent to kill what had stung him. It was now either him or us.

When the second shots hit, the bull fell in a cloud of dust, but Johan grabbed me by the shoulder, quickly pulling me to the side of the elephant.

“He could still get up,” he near-shouted into my ear. “Give him another shot for insurance,” I pressed the trigger, the rifle roared one last time and everything was still.

In awe, I stepped over and touched the bull’s immense body, felt the roughness of his wrinkled skin and admired the beauty of his tusks. With congratulatory handshakes all around and my pulse inching down closer to normal, I propped my rifle on a thornbush. Not a little shaken, a spate of emotion washed over me, and I felt like laughing and crying and running away, all at the same time. I am not ashamed to admit that I then experienced the most overwhelming sense of hunter’s remorse I have ever felt. Not wanting to talk to my companions or even face them for a bit, I wondered if these feelings represented some weakness I had never discovered in myself before. I walked around the clearing for some time while trying to cope with the enormity of what I had done.

A Tswanna tracker points out game to lohan Calitz, Butch Searcy and apprentice PH Garth Robinson on the marshlands of Okavango Delta.

After nearly half-an-hour of basically Circling the fallen giant, I finally came to the realization that shooting this elephant was simply part of the chain of life, where death of some form is inevitable. That it had been at my hands was only a detail in the great scheme of things and for this elephant, this “grand old man” as Johan so eloquently described him, to be immortalized in photographs and words was perhaps better than his starving to death in just a few short years, a shell of his former strength.

The bull was beyond my wildest dreams. I had told Johan at the beginning of the safari that I tended to be a lucky hunter, but none of us had ever thought that we would find such a elephant. His right tusk, measuring 19 inches around at the lip and well over six feet long on the curve, weighed 74 pounds. The thicker-yet left tusk, even with eight inches or so broken off, still weighed 73 pounds and would have topped 80 had it been whole. The bull will probably rank in the top five taken in Botswana in 2000 and was one of the largest killed in Africa last season.

His ivory tusks, with their creamy, glowing whiteness and intricate patterns of surface cracks from decades of wear, along with the character of the broken tip, perhaps shattered decades ago — to my eyes, were beautiful beyond describing. They will forever be a magnificent reminder of the grandest hunt of my life.

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now