It might be hard to believe, but there was a time before hunters posted “Who hunts in the rain?” and “Not seeing any deer!” updates from the treestand. A time before the rise of Deer Hunting & Food Plot Facebook Groups, before forums for just about every hunting topic existed. Before computers, cell phones and texts, when we actually interacted face to face. It was before we’d heard of “hinge cuts” and “kill plots,” when the pace of life was more deliberate and more real. A time when the world was not viewed through a digital screen, but in the analog warmth of Kodachrome film.

It was a time known as the 1970s. Good years for most of us, and a wonderful era to grow up in the hills of western Pennsylvania, roaming the woods with a .22 rifle and a pocketful of shells.

In the ‘70s, children were largely unsupervised–left to the backyard, the woods, and the tough justice of the neighborhood. Since my friends and I didn’t have video games, we invented our own pastimes. One game we colloquially called “Stick.” We played Stick by facing each other, and taking turns sticking a pocketknife firmly into the dirt as close to your buddy’s foot as possible. The closest “stick” to a foot won. Knife handle touching a sneaker? Automatic win! Of course, if you pulled your foot away, you were subjected to merciless ridicule. Did we ever play barefoot? Perhaps.

In the ‘70s kids could make mistakes and then learn to navigate out of those mistakes on their own. Moms and dads loved us, but didn’t want to be all “up in our grill.” The system worked; I’m still here and still have most of my toes.

Supposing I did hurt myself, my Italian mom was always ready to console with a loving hug and an amazing meal. Her warm demeanor was a stark contrast to Dad’s personality. He was mostly a distant, imposing figure. But when he got involved, he went “big.” And he did something for me in those years that had an incalculable influence on my life. He took me hunting.

The author’s father, Phil Messina, during World War II

Hunting for dad began after World War II. During the war years, Phil Messina marched across Europe fighting Nazis and mopping up trouble in French and German towns as a TEC 5 infantryman the 7th Army. In Germany, he received orders to hold a bridge that Russian solders wanted to cross. The encounter escalated, with guns drawn on each side, but thankfully Dad didn’t have to use his M-1 carbine. Suffice it to say, no one crossed the bridge that day, WWIII never happened and good sense prevailed.

Near the end of the war my father’s regiment went on to help free Russian Jews at Dachau, a notorious concentration camp in Bavaria. His little brother, Joe, fought in the Pacific Theatre. Joe lost his life in the intense fighting on the island of Iwo Jima. A portrait of a handsome, smiling young man in his Marine uniform, forever young, is all I know of my uncle Joe. What we owe to all the brave men who fought and perished we can never repay. But let’s get back to the shotgun story.

When the war ended, Phil Messina came home to his beautiful wife and a job at Bethlehem Steel. He started a “baby boom” family of seven children, and I was the baby. After facing the unbelievable carnage of war—not to mention all those crying babies–he sought out a diversion, a time to be alone. Like many other veterans returning home, he found quiet in the woods and a respite in hunting.

He purchased a brand new L.C. Smith shotgun, “The Gun That Speaks For Itself,” according to the adverts of the day. These were some of the finest shotguns available at the time. His “Sweet Elsie,” as the guns were affectionately called, was made in 1946. It’s a field grade model, light, quick to the shoulder and built to last. A hunter’s gun.

The new L.C. must have had pretty bluing on the 26-inch barrels, but I never saw it like that. I’d only ever seen it with shiny steel, the bluing worn away from numerous hunting trips through briars, rain and snow. It’s “boom” signaled the end of days for many a rabbit, squirrel, quail or grouse, all of which went on to become dinner at the Messina household. Dad loved to hunt, and we all loved wild game.

As a young child, I would sit with him after the hunts as he ran an oiled cloth through the breech, amazed by the color in a pheasant’s tail feathers, the softness of a rabbit’s fur. Maybe that’s why Dad pegged me for a hunter.

When I turned 12 he surprised me with a shotgun of my own, a new Savage Fox Model side-by-side. It had a wide stock and forend compared to his sleek L.C., but no gift I have ever received since has made me happier than the day he handed it to me. The barrels glowed a deep blue-black with a raised vent rib, brass beads and an engraving of a fox on the underside of the receiver. I can still remember the weight of it in my hands.

Savage Fox Model side-by-side with fox engraving

A few weeks later, Dad, brother Joe–namesake of my uncle–and I headed to our hunting spot in a ‘69 Chevy Bel Air along with Queenie, our beagle. Queenie “came from blue-ribbon stock,” Dad told me. When she ran a rabbit you could hear her bugle a mile away. Dad wasn’t the sort to brag, but he loved a good beagle and was known to talk up our Queenie. I liked listening to Dad and Joe strategize about the coming hunt.

After pulling my shiny new shotgun out of the trunk, I broke the action and dropped #6 high brass shells into the breech for the first time. We spread out in a cutover of small trees and thick briars. I carried my double barrel safely, with full control of the muzzle, fully aware of the awesome power I held in my hands.

“Hunt em up! Yuh yuh yuh yuh!” my dad called, and the excitable Queenie scrambled off in a zig-zag pattern, gone in a flash. Within a few minutes her loud bugle shattered the cool air 100 yards ahead.

Much time had been spent instructing me how to shoot my new gun; to line up the bead, to lead a runner, to shoot confidently. I hoped it would all pay off.

Soon, Queenie’s high-pitched bay began getting louder. The rabbit turned to the left, circling back to us. Dad motioned me forward, and I walked ahead, with Joe on my left and Dad on my right. Queenie’s bark was loud now; the rabbit must be near. I felt my breathing increase, and my young heart began to beat harder.

About 30 yards ahead, a big woods rabbit burst out of the brush in a loping hop, directly toward me. I raised my shotgun to my cheek, looking down the top of the side-by-side barrels for the first time in a hunting situation. Tracking the rabbit with the brass bead, at the precise moment it paused to look back towards Queenie, I fired the Savage’s improved cylinder barrel. It all happened intensely fast, but felt like slow motion; the sublime feeling of hunting.

“You got ‘im!” Dad said, just as thrilled as I was.

“You got ‘im!” Dad said, just as thrilled as I was.

Then, Kodachrome moments: Queenie retrieving the rabbit, wagging her tail the whole time; brother Joe–much older than I and already a young lawyer–smiling broadly and shaking my hand; Dad putting the rabbit in my hunting jacket and the delicious meal of braised rabbit and wine sauce my mom cooked; all vivid snapshots that are fixed forever in memory.

That old Savage 12-gauge punched my shoulder every time I shot it, and I loved it. There would be many more rabbit hunting trips with Queenie, and many more hunts for white-tailed deer with Dad and brother Joe. But those are other stories.

Many years later, after dad passed away, my five older brothers and I gathered in Joe’s law office to discuss the estate. When we got to talking guns, Joe set his papers down and stepped forward. Everyone knew the significance of the L.C. Smith shotgun. Of all dad’s earthly possessions, the sturdy, elegant gun almost seemed a part of him.

Joe said the L.C. Smith was a fine shotgun. He knew all the brothers would appreciate having it. But it was Dad’s wish the L.C. Smith to go to me.

This final gift from Dad touched me beyond words. He knew I was a kindred spirit, one who finds refuge in and appreciates the quiet beauty of the woods, just like he did. Handing me that first side-by-side years ago steered me onto the path that ultimately became my life’s passion. I work for a wildlife agency, with hunting and fishing running through my whole career. Giving me his personal gun, his Sweet Elsie, closed the loop, brought everything full circle.

I don’t take it out often, just on special occasions, but I still carry Dad’s gun into the field. I’ve shot grouse with it in the cool of February and doves in the heat of September. It’s an awesome gun to shoot. Dad’s Sweet Elsie reminds me there are objects of wood and steel that can be more than the sum of their parts. It reminds me of how important it is to remember who we are and where we came from. And in this frenzied digital age we currently find ourselves in, it’s good to slow down once in a while to remember the people we love, and the times gone by.

I just might give brother Joe a call today, and take that old L.C. Smith out on a rabbit hunt.

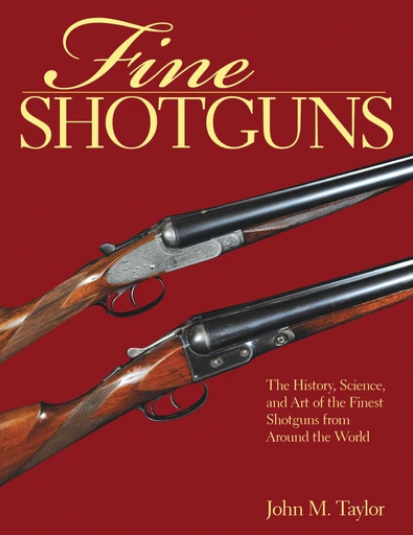

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case.

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case.

John M. Taylor began hunting with his father at age five. For the past thirty-five-plus years, he has written for major outdoor publications, including Petersen’s Hunting, Gun Dog, The American Rifleman, Outdoor Life, and more. He is currently the shotgunning editor of Sports Afield, Delta Waterfowl, and Pheasants Forever magazines. He lives in Lorton, Virginia. Buy Now