Sharing your fly rod, rifle or shotgun with a guide can be as rewarding as using them yourself.

To this day I’ve never actually fired the old shotgun. It’s an ancient Winchester Model 12 with a plain, well-worn walnut stock and was in my hands on that cool spring morning in the mountains of northern New Mexico on what became the most gratifying western turkey hunt I’ve ever experienced.

The gun is owned by Ben Garrett, the best hunting guide and one of the finest friends I’ve ever known. Ben and I have roamed New Mexico for decades in pursuit of everything from bear, elk and mule deer to coyotes, trout and blue grouse—and, of course, Merriam’s turkeys. So when I showed up for the final few days of turkey season that spring, we headed out together, Ben carrying his big Benelli and me carrying his aforementioned Winchester, intent on making a last ditch, all-out attempt to end the career of one particularly wily old gobbler who had stymied Ben’s efforts to outsmart him for the entire season so far.

I’ve told you the story before and will be happy to email it to you to read again if you wish. But for now, suffice it to say that when the old bird finally responded to our calls and decided to engage us, relative positioning and situational tactics dictated that I assume the role of temporary guide and caller, while Ben remained silent and hidden in the edge of the oak brush and spruce as I backed away and sweet-talked the big gobbler to within 17 yards of him and his waiting Benelli. It was the most satisfying hunt we’ve ever had together—at least so far.

I have always enjoyed swapping roles with a guide. I usually make it a point to hand my gun to Todd or Randy or Drew at some point while hunting autumn quail with them down in South Georgia. Captain Toby caught the biggest redfish I’ve ever seen in a side channel off Cumberland Island one warm summer morning when I offered him my fly rod and asked him to show me how it’s done. And on a cool November evening a year and a half later, my pal Goof Findlay made one of the toughest shots I’ve ever seen on a tasty young boar hog along the edge of a broad palmetto swamp in northern Florida with my custom-built Ruger No. 1 single-shot.

But it was while fishing Patagonia’s legendary Rio Malleo with my trout guide and new best friend Mark Lewis that I was witness to what is arguably the most intense display of fly-fishing focus I have ever beheld.

Fishing the rivers of Patagonia had always been on my dream list—right up there with bowhunting Alaska for coastal brown bears or driving sports cars at Le Mans or climbing Everest or hiking the Yellow Brick Road. So when the chance to fish some of those story-book rivers finally presented itself, I was all in.

The adventure began in earnest when my plane touched down in San Martín de los Andes. We spent the first few days at Lucas Rodriguez’s Tres Rios Casa de Campo plying the waters of the Chimehuin and the Collón Curá, along with a lovely little spring creek with no name. Mark Lewis is one of the most highly respected fly-fishing guides in the world and knew these rivers well—and most importantly how to share them with first-time visitors from afar. We quickly became pals, and by the end of our first day on the Chimehuin we were jesting and bantering like we’d known each other for years as I tried to adequately absorb this near-mythic landscape through which Mark was guiding me.

After a week at Tres Rios, we relocated 50 miles west to the Estancia Loncoluan and the Olsen family’s Hosteria San Huberto to fish the fabled Rio Malleo beneath the gleaming gaze of the 12,256-foot volcano Lanín as we continued this grand Patagonia adventure.

You come to Patagonia not only to fish, but to learn all you can from some of the finest fly fishermen and fly-fishing guides in the world. And Mark Lewis is certainly one them.

So I began asking him questions. I asked his opinions. I asked for suggestions and instructions and details that might make me a better fisherman:

“What are your methods for rigging a dry fly and a dropper?”

“What color polarized lenses work best for you on a rainy day?”

“What knot do you use to tie your tippet to your leader?”

At first Mark was surprised by my inquiries and perhaps even a little hesitant to address them, for as he rightly pointed out, “You’ve been doing this for a long time…longer than I have.”

“Yeah,” I responded, “for most of my life, in fact—which means that all my bad habits are now deeply embedded and in dire need of adjustment.”

Fly line rips from the surface of Patagonia’s Rio Malleo as guide Mark Lewis strikes.

So I continued picking his brain, until he realized I was serious and began answering my questions, and offering a few unsolicited suggestions of his own:

“Try pausing a little longer on your back cast.”

“You’re flexing your wrist a bit too much.”

“You dropped your rod tip on that last cast.”

But alas, words are words and are fine, as far as they go. So from time to time I would hand Mark my fly rod, usually on the pretext of needing to shoot a photograph, or to write something down in my little pocket journal while the idea was fresh, or grab a quick granola bar to re-boot my blood sugar. But in reality, my intentions and motives were purely selfish—to observe and learn from him as he made a cast or tied a knot or approached a rising trout.

And so was the case late on that penultimate afternoon on the Malleo when I was accorded what is perhaps the most impressive display of pure fly-fishing intensity I have ever witnessed.

For six days we had been the pampered guests of Ronnie Olsen and his family and staff. Mark and I were wrapping up the afternoon and eagerly looking forward to Ronnie’s promised asado that evening, which was scheduled to begin with empanadas and salads before moving on to generous rotating servings of roasted lamb, lomo, sirloin, sausages and fresh fruit, when Mark spotted the oh-so-subtle rise of a large Spanish-speaking brown trout far back beneath the overhanging branches of a big silver poplar on the far side of the channel.

I swear, the man started to shake, and his hands began to tremble as he watched the big fish, silently wishing he had a fly rod of his own. So I slipped him my 9-foot Sage 5-weight, on the pretext that I needed to change lenses on my camera, and said, “Here…give it a try.”

What followed was a Master Class in how to approach and entice a distant rising trout. For instead of plowing directly into the river, Mark studied the fish for a full three minutes or more, then stealthily positioned himself slightly downstream and still onshore before making his initial cast.

I watched in fascination as his entire universe gradually compressed into that seamless reach of water and that single silent fish as he laid cast after delicate cast across the river and far back beneath the overhanging limbs, halting every now and then to reevaluate the trout and its cadence and movements until he eventually coaxed it to rise to his tiny offering.

Fly line ripped from the river’s surface and water leapt into the still evening air in one long gash as Mark struck. Whether the fly ever grazed the fish’s lips, or whether it slipped past its jaw without making any contact whatsoever, is of little consequence. The thing that mattered most was that Mark had convinced the trout to strike.

For me, it was a strictly graduate-level tutorial in trout psychology and the fine art of fly fishing, delivered by as exceptional an angler as I have ever been honored to share a stream.

I pray I never forget the lesson.

These stories come from the creeks and rivers of the Appalachians, to the high country and desert streams of the American Southwest, to the great salmon, rainbow and grayling waters of Alaska, and back to “the little brook trout stream where the snow monster lives.” They take you to places you may never have dared to venture. And in the end, they take you home. But wherever they take you, you will most certainly remember the journey. And you might even find yourself returning again and again along the trail these stories weave until it is indistinguishable from your own.

These stories come from the creeks and rivers of the Appalachians, to the high country and desert streams of the American Southwest, to the great salmon, rainbow and grayling waters of Alaska, and back to “the little brook trout stream where the snow monster lives.” They take you to places you may never have dared to venture. And in the end, they take you home. But wherever they take you, you will most certainly remember the journey. And you might even find yourself returning again and again along the trail these stories weave until it is indistinguishable from your own.

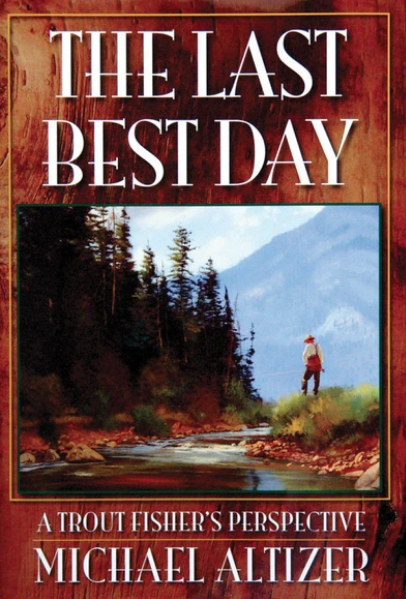

Michael Altizer’s The Last Best Day is comprised of thirty-five true-life stories covering the author’s fly fishing adventures from the creeks on the Appalachians to the high country streams of the West to the great salmon and trout waters in Alaska. 250 pages; illustrated by Brett James Smith. Buy Now