I handed a bottle of wine to my butcher. He was a big man, could probably lift a deer carcass up to the hook with one hand. But he never did. He made you do it. He turned the bottle over in his massive paw and frowned at it.

“What do I do with this?” I’d never been asked that question when gifting someone wine.

“It’s from our vineyard,” I said. “As a thanks for helping me out with that deer last season. You remember, when my dog ran off with the head?”

One corner of his mouth turned up. I’d never got him to smile before. Score one for the team.

“You drink wine, don’t you?” I said.

“Nope, the wife won’t let me.”

I’d met his wife on several occasions. She was half his size and sweet as blackberry pie. But she also had the final say on things. God alone knows the cosmic mysteries of our matrimonial relationships.

I shrugged. “Oh well, I’ll put it back in the cellar.”

“I’ll cook with it,” he said.

“Okee-doke. Hey, I got a question for you.”

He gave me an annoyed look.

“I’ve been running into a ton of bear sign where I deer hunt. What’s the story with bear? Do they taste good?”

“I hate bear.”

“Really? Why’s that?”

“They’re filthy animals.” He scratched at a piece of something tubular stuck to his apron. I tried to identify it. Trachea?

“Are they all that way? I mean, how do they taste?”

“It all depends on what they’ve been eating. High-country bears are pretty good. Some folks like ‘em. Low-country bears, those that’re eating garbage, taste like that…garbage.”

I hunt at around 6,000 feet. “So a high-country bear might be pretty good?”

He shrugged and walked back into the freezer. He was all done with talking. So I decided to get a bear tag.

Next thing I knew it was fall and I was bowhunting the western slope of the Sierra Nevada mountains in northern California. The black bear population has exploded in the Golden State since they were classified as a game animal in 1948. In the 70 years since that time, regulations have gotten more restrictive and population management and monitoring proven successful. In the early 1980s, the population estimate was around 13,000 animals. By 1998, the number had risen to 20,000. Today the estimate’s closer to 30,000, and some argue it’s significantly higher.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife allows a total 1,700 bears to be taken in a season, and every successful hunter must present the head to a department office. Biologists then extract a premolar tooth, section and stain it, and count the rings. The data is compiled and the department generates a matrix of age, sex, and distribution of animals killed over the course of each season. Hunters supply some of the most valuable data concerning the state’s black bear population and health.

I’ve witnessed the population explosion firsthand. On a whim, I set my trail camera where a fallen tree crossed a small stream in the area where I deer hunt. There were heavy game trails on both sides, and I was curious about whether the animals actually crossed on the tree. When I downloaded the pictures, I was stunned. In 24 days, I had pictures of one deer and nine different bears.

Everyone I hunted with had seen more bear sign than deer sign in the last several years. But despite that, nobody I knew had ever killed one, much less eaten one. That’s why I talked to my butcher. There are three people in this world you have to trust: your pastor, your mechanic and your butcher. And that’s not in order of importance.

It was mid-morning and I was slowly working my way across a northern slope in pretty heavy cover of manzanita and pine. The wind was blowing cross-slope and I took my time, picking my way from one game trail to the next, minding each step, pausing whenever I snapped a twig. That’s when I heard movement.

Funny, the difference between a deer and a bear moving through the undergrowth. There’s no real comparison. Where deer choose the most silent path and pick their way from step to step, black bears seem to purposefully crush everything in their way. I suppose it’s the difference between a prey animal and one that isn’t.

Crunch. Crunch. Snap. Crash. That’s the sound, getting louder as it approaches.

Fifty yards out, I saw a hump of dark fur glide over some brush and disappear, the hint of movement that goes so quickly you wonder if you really saw it at all. But the crescendo of smashing brush, that was real.

Based on his direction, I anticipated the bear would emerge in a clearing 40 yards downslope. I climbed up on a tree stump and turned sideways. The wind was perfect, gently shifting right to left. I wish I could see that ghostly thing we call scent. When I watch smoke rising from a fire and see it twisting and rolling and spreading out around me, I wonder if that’s what it’s like having the nose of a bear.

I closed my eyes for a brief moment and tried to get my heart to stop slamming in my chest. I was confident at that range, but he was farther down the hill. And in hindsight, that may have been the problem. But I was also standing on a tree stump, watching the bear close the distance between us, and there’s also that.

I closed my eyes for a brief moment and tried to get my heart to stop slamming in my chest. I was confident at that range, but he was farther down the hill. And in hindsight, that may have been the problem. But I was also standing on a tree stump, watching the bear close the distance between us, and there’s also that.

Excuses be damned. I opened my eyes and there he was, slowly lumbering across the clearing. He seemed big. But then, every bear I’ve ever seen in the woods looks monstrous. I drew and tried my best to settle the pin.

It was perfect. A clear lane through the trees between his broadside chest and my arrow. He even stopped and lifted his shaggy head. I often wonder why that happens. Do animals possess a sixth sense of things, a wariness to danger that causes them to pause in that brief instant before the shot? There’s no perceivable reason for it—no scent, no sound, no movement, nothing but an extrasensory anticipation of danger.

I set the pin just south of his shoulder and recited the words I say every time I shoot. Magical words that slow the world and bring it all back to the physical. Then I released.

I suppose that’s where it all went wrong. Hard to know. Was it the downward angle? Was it my racing heartbeat? Was it some other overlooked subtlety? A nick in one of the blades? A bent fletching? A sudden burst of wind? With bowhunting, the devil’s in the details, or so they say.

I keep a mental snapshot of that moment of impact, my green and yellow fletching entering his side. It looks good. But maybe it’s low, and with the steepness of the slope, the arrow would angle down even more on its exit.

Regardless, the bear spun on his heels and tore into the brush, back in the direction he’d come. So I knew I’d hit him. I listened to the crashing and made a mental note of the direction. And then there was silence.

Based on how long it took, I knew he’d gone pretty far, but I didn’t know if he’d continued across the mountain or dropped just out of earshot. I sat down on the stump and tried to catch my breath. Replaying the scene for the first time in what would be a thousand more. We hunters obsess, don’t we?

I wanted to rush down the slope, search for my arrow, look for blood. But I waited. Never having shot a bear before I didn’t know how long I should wait. I only gave it 30 minutes. Another mistake.

When I couldn’t take it any longer, I followed the path of my arrow. I found it in the clearing, the entire shaft bloody, with black hairs wedged in the blades. The ground was tore up where he’d spun, and his tracks were easy to see on the damp ground. I quivered my bloody arrow, nocked another one and followed him. Twenty yards into the bush, I found the first splash of blood.

I tracked him for a quarter-mile. There was a good amount of blood and every few steps I expected to see him. But he just kept going. He angled uphill and paused in a small clearing and did a few circles. Maybe he was licking the wound. He crapped and there wasn’t any blood in it. Then he kept going.

From that point on, the blood trail got thinner, sparser. I could still follow it, but the distance between spatters grew longer and longer. Eventually, he led me into a manzanita thicket. I had to leave my bow on the ground and crawl in to follow him. I found his hair on several leaves, but the blood that was bold splashes earlier had now become tiny drops. I searched from leaf to leaf. That’s when I heard crashing in front of me. Maybe 30 yards away, smashing through the brush and away. Then silence.

I found the last spot where he’d stopped and listened to me crawling toward him. But from that point on, there was nothing: no blood, no tracks, no hair. Just an aching void. I spent the rest of the day searching. I walked back and forth along the blood trail, marking it with tape, looking for something I’d missed. I walked slowly, expanding my circles around the last spot I’d seen him.

I drove home and got my dog and brought him up. He smelled the blood and I followed him across the mountainside, but soon he was tracking raccoons and deer.

The next day, I brought a hunting buddy to the spot, and we scoured the area again. I showed him the blood, as if to confirm I hadn’t imagined it all. He nodded, but he’s a dove hunter and the way he eyed the undergrowth, I could tell he was a little nervous about tracking a wounded bear into that tangle.

Every day that passed was more and more depressing. I consider myself an ethical hunter. I take conservative shots. I harvest what the good Lord puts in front of me. And I eat what I kill. So the thought of wounding and losing such a magnificent creature was devastating.

I suppose if you hunt long enough, you eventually end up feeling that. As much as we all try to kill as cleanly and efficiently as possible, sometimes it doesn’t work out like that. I guess that’s the weight of it. That all meat comes with a price. Not the sticker on a cellophane wrapper, but the real price. A life.

That bear haunted me. I dreamt about him. I visited that spot for the rest of the season, and it was like returning to the scene of a crime and every time the sunset forced me to leave, I felt a terrible weight on my shoulders.

A year passed and I debated getting another tag. I told myself that I would have it on hand and only use it during the rifle season. That I wouldn’t shoot another bear with a bow. Why the hell do we say things like that?

I was on the other side of the same mountain and deep in the timber on a narrow game trail scattered with fresh deer sign. I’d just found a shed from the previous year and tucked it into my belt. Then the crashing came. I could tell by the noise there were two of them. The wind was good and they were making their way upslope, browsing on manzanita berries and acorns.

I held tight and didn’t move. Then I saw him. He was 60 yards out and heading away from me, but just seeing him was enough to make the day a success. Then he turned and wandered toward me. I watched the rise and fall of his shoulder blades beneath that thick chocolate-colored pelt. His head was low, and every so often he would stop and eat. And all the while he drew closer. The wind was good the whole time and I was in full camo and not moving but to breathe.

At 20 yards away, the bear was still coming straight at me, but the brush was thick between us and I hoped he would choose an easier path. At 15 yards, he turned onto a game trail and passed me broadside. I put the arrow into him at 12 yards.

He growled and turned on it, then tore off into the brush. I didn’t move. I mentally marked the pine tree where I’d last heard him. I didn’t make a sound, not a damned movement either.

Then suddenly the second bear was there; I was so distracted by the first, I hadn’t even heard him approach. He sniffed the ground where I’d hit his companion and then wandered on.

I sat down and waited for two hours. I’d made the mistake of starting too early before and I wasn’t going to do it again. I tried to eat, then rest, then clean the dust off my bow. I wasn’t able to do any of it. So I prayed instead, then checked the time and prayed again.

Half my arrow was on the ground. When he turned on it, he’d bit it in half. I shivered thinking of the power in a jaw capable of biting through carbon fiber. It wasn’t a good sign. It meant I didn’t get a pass through, so I’d struck something with the tip, perhaps his shoulder blade. Even worse was the lack of blood. There wasn’t a single drop.

Half my arrow was on the ground. When he turned on it, he’d bit it in half. I shivered thinking of the power in a jaw capable of biting through carbon fiber. It wasn’t a good sign. It meant I didn’t get a pass through, so I’d struck something with the tip, perhaps his shoulder blade. Even worse was the lack of blood. There wasn’t a single drop.

I followed in the direction he’d gone, scouring the ground, searching for anything red. But there was nothing. I started to feel that slow weight settling on my shoulders again. First the half arrow, then the complete absence of blood. I picked my way down the mountainside, forcing myself to go slow. To pay attention to every little detail. Not to miss anything. Not like last time. Every silent step that took me farther from where I’d hit him was like a step into the previous year, into that terrible void of replay and regret. It just couldn’t happen again, could it? I squatted in the shade of an oak tree and set my bow down. I spun the broken arrow in my fingertips. Then I saw him.

His head was propped on a fallen pine and he had that unmistakable stillness about him. I made my way through the brush and, with every step closer, I felt that weight lifting off my shoulders, the one I’d been carrying around for the last year.

I sat down on the log next to him and ran my hand over his thick pelt, a deep tawny brown. It was a quick, clean kill, and even though he wasn’t the same bear, it made finding him that much more meaningful.

You see, we hunters know something that’s lost on most everyone else. It’s a knowledge of contrasts. That the immense value of the meat we eat is defined by the weight of the death that proceeds it. That every time an animal falls to the ground, never to rise again, we feel it. And that rare blend of sadness and joy reminds us of our connection to the equation. Our days are numbered. And valuable as a result. And we accept the weight of it because we know that every time we sit down to the dinner table, we experience a higher truth.

That afternoon I called and asked for the butcher’s wife. It was a dirty trick, I knew. But I needed to get the meat processed and he’s a damned savant with a knife and a hacksaw.

When she answered, I reminded her I was the guy whose dog ran off with his deer head. She laughed.

“So last year I talked to your husband and he said that high-country bears can be pretty good eatin’. Well, I just killed one and I was wondering if maybe…”

“Oh,” she said. “He hates bears.”

“Yeeeah, I remember that. But he’s the best butcher I’ve ever worked with and you’re as sweet as blackberry pie and…”

“Oh stop your blabbing and bring him in.”

I dropped the bear off that afternoon. I made sure the butcher wasn’t holding any knives when I came in.

“Oh,” he said. “It’s you.”

“What’d you think of the wine?”

“What wine?”

“Never mind. Hey, did your wife mention I got a bear I was hoping to get processed?”

He gave me a look that was full of expletives. “I hate bear.”

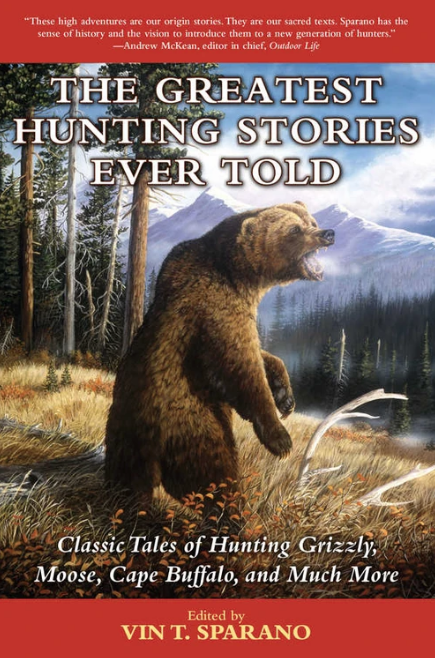

The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now

The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now