Some people are under the impression that all that is required to make a good fisherman is the ability to tell lies easily and without blushing; but this is a mistake.

The neighborhood of Streatley and Goring is a great fishing center. There is some excellent fishing to be had here. The river abounds in pike, roach, dace, gudgeon and eels, just here; and you can sit and fish for them all day.

Some people do. They never catch them. I never knew anybody catch anything, up the Thames, except minnows and dead cats, but that has nothing to do, of course, with fishing! The local fisherman’s guide doesn’t say a word about catching anything. All it says is the place is “a good station for fishing;” and, from what I have seen of the district, I am quite prepared to bear out this statement.

There is no spot in the world where you can get more fishing, or where you can fish for a longer period. Some fishermen come here and fish for a day, and others stop and fish for a month. You can hang on and fish for a year, if you want to; it will be all the same.

The Angler’s Guide to the Thames says that “jack and perch are also to be had about here,” but there the Angler’s Guide is wrong. Jack and perch may be about there. Indeed, I know for a fact that they are. You can see them there in shoals, when you are out for a walk along the banks: they come and stand half out of the water with their mouths open for biscuits. And, if you go for a bathe, they crowd round, and get in your way, and irritate you. But they are not to be “had” by a bit of worm on the end of a hook, nor anything like it — not they!

I am not a good fisherman myself. I devoted a considerable amount of attention to the subject at onetime, and was getting on, as I thought, fairly well; but the old hands told me that I should never be any real good at it, and advised me to give it up. They said that I was an extremely neat thrower, and that I seemed to have plenty of gumption for the thing, and quite enough constitutional laziness. But they were sure I should never make anything of a fisherman. I had not got sufficient imagination.

They said that as a poet, or a shilling shocker, or a report, or anything of that kind, I might be satisfactory, but that, to gain any position as a Thames angler, would require more play of fancy, more power of invention that I appeared to possess.

Some people are under the impression that all that is required to make a good fisherman is the ability to tell lies easily and without blushing; but this is a mistake. Mere bald fabrication is useless; the veriest tyro can manage that. It is in the circumstantial detail, the embellishing touches of probability, the general air of scrupulous — almost of pedantic — veracity, that the experienced angler is seen.

Anybody can come in and say, “Oh, I caught 15 dozen perch yesterday evening;” or “Last Monday I landed a gudgeon, weighing 18 pounds, and measuring three feet from the tip to the tail.”

There is no art, no skill, required for that sort of thing. It shows pluck, but that is all.

No; your accomplished angler would scorn to tell a lie, that way. His method is a study in itself.

He comes in quietly with his hat on, appropriates the most comfortable chair, lights his pipe, and commences to puff in silence. He lets the youngsters brag away fora while, and then, during a momentary lull, he removes the pipe from his mouth and remarks, as he knocks the ashes out against the bars:

“Well, I had a haul on Tuesday evening that it’s not much good my telling anybody about.”

“Oh! why’s that?” they ask.

“Because I don’t expect anybody would believe me if I did,” replies the old fellow calmly, and without even a tinge of bitterness in his tone, as he refills his pipe and requests the landlord to bling him three of Scotch — cold.

There is a pause after this, nobody feeling sufficiently sure of himself to contradict the old gentleman. So he has to go on by himself without any encouragement.

“No,” he continues thoughtfully; “I shouldn’t believe it myself if anybody told it to me, but it’s a fact, for all that. I had been sitting there all the afternoon and had caught literally nothing — except a few dozen dace and a score of jack; and I was just about giving it up as a bad job when I suddenly felt a rather smart pull at the line. I thought it was another little one, and I went to jerk it up. Hang me, if I could move the rod! It took me half-and-hour – half-an-hour, sir! -to land that fish; and every moment I thought the line was going to snap! I reached him at last, and what do you think it was? A sturgeon! A 40-pound sturgeon! taken on a line, sir! Yes, you may well look surprised I’ll have another three of Scotch, landlord, please.”

And then he goes on to tell of the astonishment of everybody who saw it; and what his wife said when he got home, and of what Joe BuggIes thought about it.

I asked the landlord of an inn up the river once, if it did not injure him, sometimes, listening to the tales that the fishermen told him; and he said:

“Oh, no; not now, sir. It did used to knock me over a bit at first, but, lor love you! Me and the miss us we listens to ’em all day now. It’s what you’re used to, you know. It’s what you’re used to.

I knew a young man once, he was a most conscientious fellow, and, when he took to fly fishing, he determined never to exaggerate his hands by more than 25 percent.

“When I have caught 40 fish,” said he, “then I will tell people that I have caught 50, and so on. But I will not lie any more than that, because it is sinful to lie.”

But the 25 percent plan did not work well at all. He never was able to use it. The greatest number of fish he ever caught in one day was three, and you can’t add 25 percent to three – at least, not in fish.

So he increased his percentage to 33 and 1/3; but that, again, was awkward, when he had only caught one or two; so to simplify matters, he made up his mind to just double the quantity.

He stuck to this arrangement for a couple of months, and then he grew dissatisfied with it. Nobody believed him when he told them that he only doubled, and he, therefore, gained no credit that way whatever, while his moderation put him at a disadvantage among the other anglers. When he had really caught three small fish, and said he bad six, it used to make him quite jealous to hear a man, whom he knew for a fact had only caught one, going about telling people he had landed two dozen.

So, eventually, he made one fin al arrangement with himself, which he had religiously held to ever since, and that was to count each fish that he caught as 10, and to ass u me ten to begin with. For example, if he did not catch any fish at all, then he said he had caught ten fish ‑ you could never catch less than 10 fish by his system; that was the foundation of it. Then, if by any chance he really did catch one fish, he called it 20, while two fish would count 30, three 40, and so on.

It is a simple and easily worked plan, and there has been some talk lately of its being made use of by the angling fraternity in general. Indeed, the Committee of the Thames Angler’s Association did recommend its adoption about two years ago, but some of the older members opposed it. They said they would consider the idea if the number were doubled, and each fish counted as 20.

If ever you have an evening to spare, up the river, I should advise you to drop into one of the little village inns, and take a seat in the tap-room. You will be nearly sure to meet one or two old rodmen, sipping their toddy there, and they will tell you enough fishy stories, in half an hour, to give you indigestion for a month.

George and I and the dog went for a walk to Wallingford on the second evening, and, coming home, we called in at a little river-side inn, for a rest, and other things.

We went into the parlor and sat down. There was an old fellow there, smoking a long clay pipe, and we naturally began chatting.

He told us that it had been a fine day to-day, and we told him that it had been a fine day yesterday, and then we all told each other that we thought it would be a fine day to-morrow; and George said the crops seemed to be coming up nicely.

After that it came out, somehow or other, that we were strangers in the neighborhood, and that we were going away the next morning.

Then a pause ensued in the conversation, during which our eyes wandered round the room. They finally rested upon a dusty old glass-case, fixed very high up above the chimneypiece, and containing a trout. It rather fascinated me, that trout; it was such a monstrous fish. In fact, at first glance, I thought it was a cod.

Then a pause ensued in the conversation, during which our eyes wandered round the room. They finally rested upon a dusty old glass-case, fixed very high up above the chimneypiece, and containing a trout. It rather fascinated me, that trout; it was such a monstrous fish. In fact, at first glance, I thought it was a cod.

“Ah!” said the old gentleman, following the direction of my gaze, “fine fellow that, ain’t he?”

“Quite uncommon,” I murmured; and George asked the old man how much he thought it weighed.

“Eighteen pounds six ounces,” said our friend, rising and taking down his coat. “Yes ,” he continued, “it wur 16 year ago, come the third O’ next month, that I landed him. I caught him just below the bridge with a minnow. They told me he wur in the river, and I said I’d have him, and so I did. You don’t see many fish that size about here now, I’m thinking. Good-night, gentlemen, good-night.”

And out he went, and left us alone.

We could not take our eyes off the fish after that. It really was a remarkably fine fish. We were still looking at it when the local carrier, who had just stopped at the inn, came to the door of the room with a pot of beer in his hand, and he also looked at the fish.”

Good-sized trout, that,” said George, turning round to him.

“Ah, you may well say that, sir,” replied the man; and then, after a pull at his beer, he added, “Maybe you wasn’t here, sir, when that fish was caught?”

“No,” we told him. We were strangers in the neighborhood.

“Ah!” said the carrier, “then, of course, how should you? It was nearly five years ago that I caught that trout.”

“Oh! was it you who caught it, then?” said I.

“Yes, sir,” replied the genial old fellow. “I caught him just below the lock – leastways, what was the lock then -one Friday afternoon; and the remarkable thing about itis that I caught him with a fly. I’d gone out pike fishing, bless you, never thinking of trout, and when I saw that whopper on the end of my line, blest if it didn’t quite take me aback. Well, you see, he weighed 76pound. Good-night, gentlemen, good-night.”

Five minutes afterwards, a third man came in, and described how he had caught it early one morning, with bleak; and then he left , and a stolid, solemn-looking, middle-aged individual came in, and sat down over by the window.

None of us spoke for a while; but at length , George turned to the newcomer, and said:

“I beg your pardon, I hope you will forgive the liberty that we — perfect strangers in the neighborhood — are taking, but my friend here and myself would be much obliged if you would tell us how you caught that trout.”

“Why, who told you I caught that trout!” was the surprised query.

We said that nobody had told us so, but somehow or other we felt instinctively that it was he who had done it.

“Well, it’s a most remarkable thing — most remarkable,” answered the stolid stranger, laughing; “because, as a matter of fact, you are quite right. I did catch it. But fancy your guessing it like that. Dear me, it’s really a most remarkable thing.”

And then he went on, and told us how it had taken him half an hour to land it, and how it had broke his rod. He said he had weighed it carefully when he reached home, and it had turned the scale at 34 pounds.

He went in his turn, and when he was gone, the landlord came in to us. We told him the various histories we had heard about his trout, and he was immensely amused, and we all laughed very heartily.

“Fancy Jim Bates and Joe Muggles and Mr. Jones and old Billy Maunders all telling you that they had caught it. Ha! ha! ha! Well, that is good,” said the honest old fellow, laughing heartily, “Yes, they are the sort to give it me, to put up in my parlor, if they had caught it, they are! Ha! ha! ha!”

And then he told us the real history of the fish. It seemed that he had caught it himself, years ago, when he was quite a lad; not by any art or skill, but by that unaccountable luck that appears to always wait upon a boy when he plays the wag from school, and goes way out Fishing on a sunny afternoon, with a bit of string tied on to the end of a tree.

He said that bringing home that trout had saved him from a whacking, and that even his schoolmaster had said it was worth the rule-of-three and practice put together.

He was called out of the room at this point, and George and I again turn ed our gaze upon the fish.

It really was a most astonishing trout. The more we looked at it, the more we marveled at it. It excited George so much that he climbed up on the back of a chair to get a better view of it.

And then the chair slipped, and George clutched wildly at the trout-case to save himself, and down it came with a crash, George and the chair on top of it.

“You haven’t injured the fish, have you?” I cried in alarm, rushing up.

“I hope not,” said George, rising cautiously and looking about.

But he had. That trout lay shattered into a thousand fragments – I say a thousand, but they may have only been nine hundred. I did not count them.

We thought it strange and unaccountable that a stuffed trout should break lip into little pieces like that.

And so it would have been strange and unaccountable, if it had been a stuffed trout, but it was not.

That trout was plaster-of-Paris.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2005 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

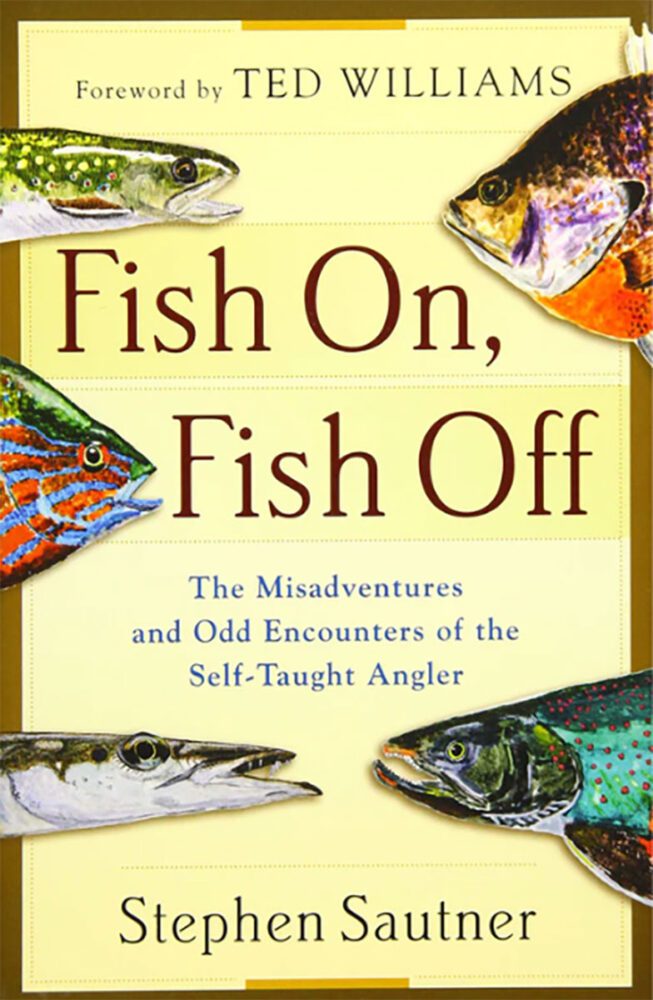

Through a series of nearly 50 personal essays, the author explores what happens when the self-taught, DIY angler sets out to fish the world—and winds up stumbling into every possible pitfall and danger along the way. These include: getting chased from a river by an elephant, surviving a terrifying helicopter ride over the Straits of Magellan, and breaking his only rod on the second cast in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs. Buy Now

Through a series of nearly 50 personal essays, the author explores what happens when the self-taught, DIY angler sets out to fish the world—and winds up stumbling into every possible pitfall and danger along the way. These include: getting chased from a river by an elephant, surviving a terrifying helicopter ride over the Straits of Magellan, and breaking his only rod on the second cast in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs. Buy Now