When he was in his 20s, both of his parents died. Turnow went home and ran the family farm for a while, but in such a shiftless way that his relatives were incensed. They, in fact, were among the first to whisper that maybe John wasn’t “all there.”

In those parts, a liking for the woods wasn’t grounds for questioning the sanity of anyone, man or boy, and a kid who could shoot like Turnow couldn’t be blamed for wanting to spend all his time hunting. Often the boy went with older men, and in a time and place of easy game laws and abundant game, they’d always return with a substantial bag of black-tailed deer, bear or at least all the blue grouse a man and his family could eat in a week.

By the time Turnow was 15, his adult hunting companions were boasting he was the best shot in Grays Harbor County. When he was in his 20s, in the early years of the century, a lot of folks were willing to take in considerably more territory than that, especially two men he hunted with frequently, Giles Quimby and Charles Lathrop. Quimby used to tell how Turnow, using a Krag-Jorgenson .30 that he’d brought back from the Spanish-American War, that he’d drilled a bear in the right eye at a distance of 300 yards, with the visibility poor.

Nobody who knew him would have thought that what Turnow could do with a rifle was going to make blazing headlines all over the U.S. They could hardly have pictured big, kindly John Turnow, who had a way with children and hated to see animals suffer, as the grisly figure he was to become in the newspaper stories: “mad killer…cold blooded murderer…savage beast…inhuman monster.”

Certainly his hunting companions, Quimby and Lathrop, would have been the last to foresee the terrible roles they and Turnow were going to play in the West’s strangest manhunt.

From the beginning, John Turnow was admittedly different — a silent sort of youngster, always at odds with his parents and teachers. His mother was a determined woman who vowed that her only son was going to amount to something more than the local louts who had no higher ambitions than to drink up the proceeds of their seasonal employment in the sawmills or timber tracts, and to hunt when they were sober. It was a blow to her when he showed no interest in education. Exasperated teachers complained that, on the increasingly rare occasions when he showed up at all, he would sit staring out the window, not hearing a word they were saying.

More and more John would come drifting home after dark, always giving the same answer to angry questions about where he’d been. “In the woods,” he would reply. Turnow didn’t tell his parents, as he did a few trusted playmates, about the things he’d seen there; about how, if you knew how, you could follow a bear’s tracks, even through the two-inch-thick moss covering the rain forest, and how you could make a chickaree squirrel come right to you if you made a kind of shrill, chattering call.

John was as bitter a disappointment to his father as he was to his mother. The elder John Turnow was a stern, red-faced man who, by dint of dawn-to-dusk labor, had turned a run-down stump farm near the town of Montesano into one of the best agricultural properties in the county. But he just couldn’t keep his son at the farm chores. The boy’s moonstruck fascination with the wildlife in the woods grew, and having the daylights whaled out of him only created a sullen resentment of his parents and of authority in general.

Nobody tried to stop the youth when he quit school at 14 and took to the woods for weeks at a stretch. By the time he was 16, and already nearly six feet tall, local hunters were hiring him as a guide. Turnow knew every corner of the southern section of Olympic Peninsula, and sometimes ventured far north to the towering mountains of what is now Olympic National Park. He fished and explored every stream of the many that tumbled toward the sea in this region of heavy rainfall, though it was the Satsop he liked best.

When he was in his 20s, both of his parents died. Turnow went home and ran the family farm for a while, but in such a shiftless way that his relatives were incensed. They, in fact, were among the first to whisper that maybe John wasn’t “all there.”

“If John Turnow’s crazy, so am I,” Giles Quimby used to say, with a grin on his long, lean face. That always got a laugh, because there was hardly a more sober, saner man around.

Quimby, who had served in the regular army, now made his living as a trapper on the Satsop and by serving as a deputy sheriff. He was known to be a sound judge of men, fair and sparingly careful with his words. If there was anybody who understood Turnow, it was Quimby. Turnow, who had been laughed at so many times for some of his odd ideas, was likely to talk in grunted monosyllables to most people, but he talked freely to Quimby. When Turnow told him how the trees spoke to him, and about how he could communicate with animals, Quimby felt an appreciation of his friend’s fine-honed senses, which enabled him to hear and see things that others missed.

Quimby understood, too, when Turnow told him how he’d felt when he went over to his uncle’s place and saw some wild horses penned up there. They’d stood up, their hooves battering the log corral fence. “It was their eyes, looking at me like I should let them out,” Turnow said. “They were wild. They hadn’t ought to be in a pen.” So he let them go.

Was a man crazy because he freed wild horses? Quimby didn’t think so. He knew how simple it had seemed to Turnow. These creatures were wild, trapped and they wanted out. It seemed, to him, the only thing to do.

And there was the time Turnow got into trouble with the law. He’d seen a hunter make a poor shot, wounding a doe. Turnow took after the doe, but even with his long, loping strides he had to chase her two miles before he caught up. After killing her with one shot, Turnow went back to the hunter, grabbed the gun from his hand, and bent the barrel out of shape. Was this crazy? Quimby had often felt just as angry with some of the shooting he’d seen. But it was things like this that helped spread the stories.

After the judge fined Turnow ten dollars and made him pay for the gun, there was considerable talk around town, particularly among the relatives. Turnow’s uncle, Will, held that he was getting violent.

“No telling what he’s likely to do,” he told everyone.

The other relatives nodded, and while Turnow was out on one of his forest jaunts in the summer of 1909, they agreed that it was time something was done. When Turnow came back, his uncle asked the big woodsman if he’d like to go along on a trip down to Portland.

“You ought to have a city doctor take a look at that sore foot of yours, John. It’s not healing right.”

Turnow thought it over and finally, the pain in his foot and curiosity about seeing the city, overcame his natural fears of such a venture.

He enjoyed the train ride down, and was awed by the town and the chugging automobiles, and the general noise and confusion. He was glad enough to go to a large building on the outskirts, which, he was told, was a hospital. Inside, Turnow was taken to a room by an attendant. He was a little troubled by the fact that his uncle didn’t come up with him.

“Wait for you downstairs,” Will had mumbled.

It took Turnow a while to realize there was something all wrong about the place he was in. This narrow, little coffin-like room that made him feel as if he were choking for breath. Then he noticed the bars on the high window.

He rushed to the door. It was locked. He shook it and then kicked it, but it didn’t give. He pushed up the window and grabbed the bars, shaking them. They didn’t budge. Then Turnow screamed, a terrible, high-pitched scream, and the door jerked open and three burly white-coated men rushed in.

Turnow tried to fight them off, but before he knew what was happening, they had him trussed up in a strange jacket. He tried to bite them, but they put a gag in his mouth and a doctor jabbed a needle in his arm.

In the morning, Turnow woke up with the jacket still on, but the gag gone. He opened his mouth and howled the eerie wail of a caged beast. The attendants, long used to desperate cries, found this the most chilling they’d ever heard.

Up in the Satsop country, the fact that Turnow had been “put away” occasioned a lot of talk. Many thought that Turnow’s folks had done right. After all, who knew what a crazy man might do? Others, like Giles Quimby, were bitter about it. Turnow would never hurt anybody, they believed, and how was he going to feel shut up like a caged animal? Maybe, they hinted, the relatives just wanted the farm. But they could do nothing.

A few weeks later, Turnow’s family got an agitated telephone call from the sanitarium: Turnow had escaped! Police in the Portland area made a thorough search, but found no trace of him. Then one night his uncle got the fright of his life. As he walked out to the barn, a shadowy figure stepped into the rays of the lantern. A gaunt, ragged, unshaven man with bright accusing eyes. Will stood frozen to the spot, his jaw open.

“You’ve got my gun,” Turnow said gruffly. “I want it.”

“You’ve got my gun,” Turnow said gruffly. “I want it.”

“What are you going to do?”

It was only after he’d wolfed a meal at the house, that Turnow told his uncle of his plans. They were harmless enough. Waving a hand out toward the north, where the forest swept down out of the mountains, Turnow said that was where he was going to live. He would never sleep in a house again.

‘‘Don’t come into the woods to take me,” he warned. Then, after a pause, he shouted the ringing words that no one in that part of the country would ever forget.

“I’ll kill anybody who tries to take me!”

There was a lot of dissension among the relatives as to what ought to be done. One group held that it had all been a mistake to begin with. Another sent an irate delegation to Sheriff Edward Payette, and told him it was his plain duty to go in there and get Turnow and take him back to the institution.

The sheriff was troubled about it, and had a talk with Quimby.

‘‘I know how you feel about John,” the sheriff said. ‘‘What do you think I ought to do? His relatives are riding me pretty hard to bring him in.”

Quimby’s eyes blazed.

“Listen,” he said, “the relatives are the ones that are crazy. Putting him in a place like that. Why can’t they leave him alone?”

The sheriff nodded. “Can’t see as he’s doing any harm out there in the woods. The way I see it, this thing’s just a family quarrel.”

The sheriff went back and told the relatives that. There was quite an outcry, but Payette, feeling that he had the backing of the community, did nothing.

Quimby was out in the forest, checking his traps one morning, when he was startled by a low voice right behind him. He wheeled. It was John Turnow. Before Quimby could say anything, Turnow spoke.

“Giles — saw the sheriff walking the woods. D’you think they’ll — they’ll try to put me in there again?”

Quimby tried to smile, to sound reassuring, but most of all to hide his shock at the change he saw in Turnow. His hair was long and uncombed, and his face was covered with a dark, scraggly beard. But most changed of all were his eyes. They had a wild, haunted look in them, a look frightening to see.

“How you making out, John?” he asked, anxious to change the subject. The haunted look went away for a few moments.

“Fishing’s good,” Turnow said. “And I got a pond with maybe fifty frogs in it. Maybe you’d like to come up and have some frog legs?”

Quimby smiled, thinking of the many times they’d feasted together on the delicacy. But the smile faded as it struck him suddenly that he couldn’t go with Turnow. He didn’t want to know where he hid out. Suppose those relatives of his did push the sheriff into something and…hell, no, he didn’t want to have any idea of Turnow’s whereabouts.

He replied, “No, not today, John,” and a sick feeling hit him in the stomach when Turnow turned to look at him. Quimby sensed that, slow as Turnow’s mind might be sometimes, there had flashed into it knowledge of what Quimby was thinking.

For close to two years, Quimby never did see where Turnow lived, and people began to forget about John Turnow. The relatives bickered among themselves, and periodically some of them badgered the sheriff to do something.

They got most excited when Quimby, at Turnow’s request, arranged a public sale of the household effects and implements on the farm that rightly belonged to him. Quimby placed John’s share, some $1,700, in a Montesano bank, and told the grateful Turnow: “This’ll keep you in tobacco and ammunition a long time, John.”

Turnow seldom ventured out of the woods, buying his few necessities at a store in Pacific Beach over on the coast, far from spying relatives. He was approaching this store in his silent way one August day in 1911, when the murmur of voices made him stop short. He’d heard his name, and suddenly his heart was beating wildly.

He crept closer. Yes, there it was again. He caught some of the words…“they’ll get him…sheriff should have done it…Bauer brothers….

Sudden terror swept Turnow, and he turned to run. They were going to try to get him! It was as if the bars were in front of him again, locking him in, as if he were fighting that binding jacket they’d put on him.

He ran on and on, blindly, through the forest. Maybe they were looking for him already…maybe he was running into a trap. He took to weaving, going off the faint trail that led along the Humptulips River and striking off into the forest, crouching, twisting in and out among the gray-barked firs.

When he finally reached it, he lay trembling in his wickiup, a bark-covered lacing of branches he’d built, well concealed in a deadfall. But even there the panic would not leave him, and it was a long time before he could sleep.

“They’re after me,” he told Quimby the next time he saw him.

Quimby tried to calm him, but it was useless.

“It’s my Uncle Will,” Turnow insisted. “Got a feeling even my sister’s turned on me.”

He covered his face with one of his big hands.

“I don’t want to have to kill anybody.”

Quimby spent a long time with him, and by the time he left, Turnow felt better. The next day, in fact, Turnow had regained enough assurance to head over to another store on the sound where he occasionally traded. Turnow needed the tobacco and ammunition he’d failed to buy at Pacific Beach. All his uneasiness seemed to come back, however, as the storekeeper waited on him. He was convinced the man was looking at him strangely. His uneasiness turned to panic when, after stepping out of the store, he looked back. The storekeeper was talking on the telephone. He was telling someone he was there…telling his relatives…they were coming for him.

Frantically, Turnow plunged again into the forest, as he had from Pacific Beach. He moved with the easy swiftness of a forest creature, but as he ran he cried, a strange, wild animal moaning.

It was the next morning when he heard the men in the forest. Two of them, Turnow’s ears told him, and his heart began to race. Two of them, coming his way, moving stealthily toward his shack. He took up his rifle and strained to see them.

From the moment Quimby had left Turnow, he had felt a growing sense of uneasiness. Turnow was apparently feeling like a cornered wild animal. If his relatives were planning anything, there would be bloodshed. Finally, Quimby decided to go down to Montesano and have a talk with Turnow’s uncle, the leader of the clan, to warn him to keep out of Turnow’s part of the forest.

Before Quimby left for Montesano on Monday, the telephone on his cabin wall jangled. Sheriff Payette was on the wire. What he had to say drove the blood out of Quimby’s face.

“The Bauer twins went into the woods two days ago, and they aren’t back. Going bear hunting, they said. I’d like you to get in on the search party we’re getting up.”

The Bauer boys! Turnow’s 18-year-old nephews!

Quimby tried to keep his voice calm. “Any idea where they went?”

“Not too much…up around the Oxbow.”

A chill went through Quimby. The Oxbow, the bend in the Satsop River, was country Turnow ranged.

A day later, after tramping the woods fruitlessly with no trace of the missing Bauers, Payette sent over to the Quinault Indian reservation to get a tracker. He got onto the boys’ trail fast enough, first finding the place where they’d spent Saturday night, and then the spot where, on Sunday morning, they’d picked up bear tracks. They’d stayed with the tracks until they led to a wild tangle of deadfall. At the edge of it, the Bauers had stood up on a fallen Stika spruce, both of them, side by side.

The Indian got up on the log too, and pointed with some surprise at what the boys must have seen. There was an odd bark wickiup, so cunningly concealed you could see it only from this point. Quimby stepped up on the log too. There was no question in his mind that he was looking at the thing he had never wanted to see — Turnow’s shack.

While he stood there frozen, a young deputy named Colin McKenzie saw something that excited his interest — an odd mound of bark and moss. He went over, probed at it with his foot, and then uttered a cry of horror.

In a few minutes, fellow searchers had drawn back the pile of bark, and there, staring up at them, were the dead eyes of the Bauer brothers. In the middle of the forehead of each was the black mark of a bullet hole.

Amid the excitement in Montesano as a posse was organized, Quimby seemed a man in a daze. Noticing the strain on his white, drawn face, the sheriff came over and put a hand on his arm.

“Rough on you, Giles,” he said. “Turnow being your friend. You want to turn in your badge? Folks would understand if you did.”

Quimby tried to talk, but words didn’t come.

“Take a little time to think it over,” the sheriff said.

Quimby tried to think it through. Hunt down Turnow? Hunt down the man who was his friend? But Turnow was a murderer. Did it make any difference that Quimby knew how Turnow had felt in the moment he had killed, how the wild panic must have swept him when he saw the Bauers standing on that log, looking at his shack? Turn in his badge? Let others track down Turnow. That would be the easiest thing…but would it be right? He was a law officer; Turnow was a murderer who had killed two men. How long would it be before the panic came on him and he killed again? In the end, that was the thought that decided Quimby. He’d keep his badge, he told the sheriff.

The manhunt started with a trail quickly picked up by bloodhounds. They went springing off through the forest, easily following the scent to the other side of the west branch of the Satsop where Turnow had evidently crossed it. Then, when they got into the thick tangle of spruce across the river, the dogs suddenly began to run around in bewilderment. It didn’t seem reasonable, but somehow they’d lost the scent and couldn’t find it again. It was as if Turnow had walked into these trees, and then the earth had swallowed him up.

After that, the sheriff realized he had a job on his hands. He swore in 200 deputies and they combed the Peninsula—up to the Olympics, west to the sea, east to Puget Sound.

Nothing.

The search went on through September and into October. Not once did they catch sight of Turnow, and when the rainy season began, the hunt petered out. Many felt certain that Turnow had left those parts.

Giles Quimby didn’t agree, though he told no one his reasons. After the posses gave up, he searched for Turnow alone. It was on these lonely jaunts that he came to feel sure that Turnow was there in the forest, watching him. He felt it first as a prickling sensation along the base of his neck. When the feeling was on him, Quimby would sit or lie perfectly still for a while, then slowly turn to examine every inch of the forest around him. There was never the slightest hint of where a secret watcher might be hidden. Yet he knew Turnow was there…somewhere.

Was Turnow really watching him? And if he were, did he know? Quimby was sure of the answer, even as he asked himself the question. Of course, Turnow knew that Quimby was after him. And if he were watching, why didn’t he pull the trigger? He knew the answer to that, too. In John Turnow’s simple logic, a man did not kill as close a friend as Quimby, even when he had joined those who were hunting him down. To Quimby, this was the most tormenting thought of all.

It was Deputy McKenzie who was up in the Oxbow country one day in the spring of 1912, getting no place with his search for Turnow, when two excited trappers appeared. Frank Getty and Louis Blair had run across the carcass of an elk, freshly butchered. Who would be killing an elk up there but Turnow?

McKenzie let out a low whistle as he listened to their story. Would they take him to the spot? Both Blair and Getty shook their heads. They’d done their duty in reporting what they’d seen; they weren’t taking any more chances. At this point, a trapper named A. V. Elmer allowed that he knew the country well, and could tell from their description about where they’d found the elk. He’d take McKenzie there. Of course, Elmer said, he’d let McKenzie do the shooting, if shooting there should be. That was all right with McKenzie, who calmly said that he wasn’t worried about Turnow.

Giles Quimby was worried, however, especially after a week went by with no word from McKenzie and Elmer. The sheriff decided he’d better start a search, and Blair took the party to the spot where he’d seen the elk, but the best trackers couldn’t find any sign of a trail leading away from it. They sent for bloodhounds, but while they were waiting, a deputy felt the earth yield a little beneath his feet and looked down. His hoarse yell brought his companions running.

When they had pushed aside the covering of moss and earth, they saw the bodies of Elmer and McKenzie. Each had a bullet hole in his forehead.

Excitement swept the Pacific Northwest.

“MAD KILLER LOOSE IN WOODS,” shouted the headlines. Endless stories were told of Turnow’s incredible accuracy. Four times he had killed, four times the shots had been placed with a terrifying sameness. Reporters poured in from wire services and the big city newspapers to report the progress of the biggest manhunt that part of the West had ever seen—600 to 700 temporary deputies, 50 officers from other towns and three teams of bloodhounds in action at the same time.

Weeks went by. They swarmed over the woods, finding traces, getting a trail and losing it, getting nowhere. Finally, the distracted sheriff called off the mass search. He and his deputies would have to continue the hunt whenever they could but, for now, they had to admit complete failure.

To spur on private citizens, the county commissioners offered a reward of $4,000 to be added to the $1,000 put up by the state. For a time, “hunting parties’’ came from all over Washington for weekend hunts for this uniquely dangerous game. As the months dragged by, and no trace of Turnow was found, wild reports began to come in from other sections of the country.

A general alarm was sent out in southern Oregon when somebody spotted a bulky figure lumbering through woods. It turned out to be a bear. A woodsman was shot and badly wounded outside his own cabin on Puget Sound. And in Mason County, near the Satsop, a burly lumberman came rushing out of the woods babbling incoherently about having seen “a monster in a tree.” His story was written off as simple hysteria.

Quimby went on looking, as was his duty, but he was not the only seeker, as he found out when he bumped into Charlie Lathrop and Louis Blair with their two Airedale dogs.

“What are you boys hunting?” Quimby asked.

“Big game,” Lathrop said with a grin. “Five thousand dollars’ worth.”

Quimby looked at his friend as if seeing him for the first time.

“You’re hunting him for the money, Charlie?”

Lathrop flushed. “What’s the matter with that?”

Quimby turned and walked away.

Later that search of Lathrop’s and Blair’s became famous. All other amateurs dropped out during the winter and early spring months, but these two and their dogs continued to rove the woods. Wiseacres nodded, and said that, barring Quimby—that is, if Quimby really wanted to catch Turnow—nobody stood a better chance of finding him. Lathrop had hunted with him; he knew his ways and tricks. And those dogs, they were smart ones.

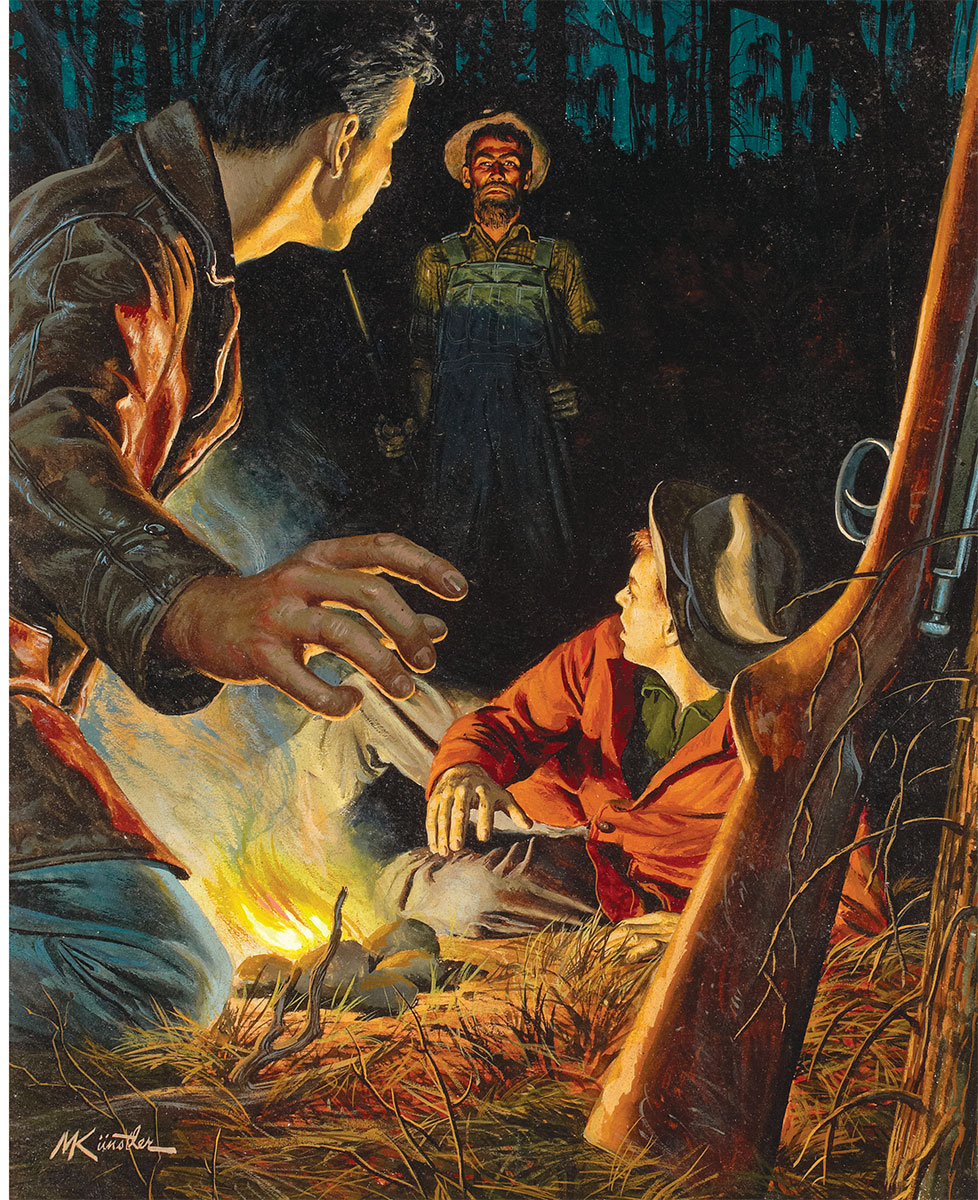

Quimby ran into them from time to time, because they ranged the same territory. On the night of April 15, 1913, they had just stopped by Blair’s cabin when Lathrop and Blair burst out of the woods.

“We’ve found Turnow’s place!”

A man named J. B. Lucas had reported to the sheriff the discovery of a small cabin, which showed signs that someone was living there. Lathrop and Blair had talked to Lucas, and had promptly set out to find the cabin. Just before dark they had come upon it, a crude structure with a bark door. They’d smelled a fire, something they’d been sniffing in the air for all these months. There had been no smoke, but the smell was unmistakable. They were convinced Turnow was inside.

With dark coming on, they decided it was no time to strike. They would come back at dawn the next day. Would Quimby go along?

Quimby stood there a moment, looking at the two men. They had no chance against Turnow; he knew that. Despite his feelings about them, he knew he could not stand by while they were slaughtered. He turned away.

“I’ll go,” he said gruffly.

Their first disagreement came the next morning. Lathrop wanted to take the dogs, but Quimby felt the animals would betray their presence.

“We’ll need them if he’s gone,” Lathrop kept saying, and at last Quimby gave in. So the dogs were along when they crept through the moss and came again in sight of the shack.

Quimby studied it a long time and then outlined a plan of action. They would close in on the cabin from three sides. Quimby would make the longest circuit, coming in from the north, the side that had the door. Blair and Lathrop would come up from the east and the south respectively. No one was to make a move until Quimby called out to Turnow.

“Keep the dogs quiet,” Quimby said, and crept away. He could hardly tell the two men, experienced woodsmen that they were, to be quiet themselves in this strange forest where the silence was so great you could often hear the whisper of spruce needles falling from a tree a hundred feet away.

He had gone perhaps 50 yards when he heard a faint clicking sound and stopped dead still. It had come from Blair’s direction. He’d dragged his rifle against something. Quimby frowned. Blair could get himself killed that way, if Turnow’s there, he thought.

When he at last reached a position where the shack was within his view, not more than 200 feet away, Quimby lay for a long time, just looking. Suddenly he saw Blair’s face. Perfect target. Every nerve in Quimby’s body was screaming: Get down, you fool!

Even if he had cried out the words, it would have been too late. The crash of a rifle ripped the silence. Blair’s face was suddenly a bright, terrible red, and then it vanished. Lathrop’s rifle hammered, at a target Quimby couldn’t see, then a thunderous silence came back to the woods. Nothing moved but the wisps of drifting gunsmoke.

So Turnow was there. Now the thing that had wrought Quimby numberless nightmares, each drenched in cold sweat, was reality.

A rifle again. Lathrop’s. And this time Quimby saw John Turnow’s bearded face as it appeared for a fleeting instant beside a tree. The time for thought was past. Trained reflex took over now as Quimby raised his gun. He got off four shots and then stopped. He couldn’t see Turnow. Again the silence, full of menace.

Had Turnow seen him? Did he know who the third man was? He felt somehow that both Lathrop and Turnow were still alive. There was only one thing to do. Wait. Quimby tried to telegraph the message to Lathrop. Wait. Wait and live. Quimby forced his muscles to relax, fighting the tension out of them. Minutes dragged by and there was no sound but the whispering of the firs, the high sweet shrilling of a distant water ouzel and, now and then, the sad whimper of Blair’s airedale, considering himself released now from the admonition of silence given by a master who no longer spoke or moved.

Quimby’s eyes swept back and forth from the tree where he knew Lathrop was hidden to the one where Turnow had been. Suddenly he saw motion. Lathrop came up, rifle thrust around the tree. It blazed instantly. Quimby did not look at it. He was staring at the other tree, and it was there again, the face surrounded by its matted tangle of hair. Even above the hammer of the guns, Quimby heard Lathrop’s scream.

For one instant, Turnow turned toward Quimby who immediately fired, his heart pounding as if it would burst. Then he threw himself behind the tree.

The silence again. Quimby wondered if he was the only one still alive. He began to crawl. He had to see if there was anything he could do for Lathrop.

There wasn’t. Lathrop lay on his back, a bullet hole through his face. Quimby crouched beside him, knowing that since no bullets had come from that other tree, Turnow was either gone…or dead. Either way, there was nothing more he could do here. Quimby edged away, finally getting to his feet and running. An hour later he was at Simpson Lumber Camp Number 5, gasping out his story to the sheriff.

Long before they reached the shack, they could hear the puzzled moaning of the dogs. Cautiously the men moved forward. Quimby came to the tree with the bullet-scarred bark and looked behind it. Turnow wasn’t there, but a second later he saw him. His lifeless body leaned against the wickiup, in a sitting position, his rifle across his knees.

Quimby looked down at him for a long time. Through the rags that covered Turnow’s body, he could see its tremendous muscular development. As Quimby knelt to take the gun from the huge hands, he saw that their palms were heavily calloused and black with pitch. Suddenly he understood about that watched feeling, about those stories of a wild creature high in the trees. Turnow had actually taken to the trees in the years he’d been pursued. He had been high in some lofty fir or spruce when the posses were beating the ground below and the bloodhounds came so mysteriously to the end of their trail.

There was no fierceness in Turnow’s eyes now, and no reproach. In them Quimby saw, instead, a kind of peace that gave him an answer to his self-accusation. Turnow died, as he would have wanted to die, alone here in the woods. Not trapped behind bars. Quimby turned away and walked off through the forest.

Later, the County Commissioners voted that the reward should go to Quimby, but it was no surprise to the people of Grays Harbor County when the money was never claimed.

Editor’s Note: “Hunt for A Wild-Man Killer” originally appeared in the November 1952 issue of True magazine. True, also known as True, The Man’s Magazine, was published by Fawcett Publications from 1937 until 1974. All efforts have been attempted to research and locate copyright information.

Leather-bound, limited edition of 500, signed and numbered by Chuck Wechsler.

Leather-bound, limited edition of 500, signed and numbered by Chuck Wechsler.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson. Buy Now