Squirrel hunting is a wonderful way for a fledgling hunter to learn his craft and then his art, whether he’s in single digits or well advanced in years.

“The child is father to the man.” When I first read these words from Zane Grey’s Tales of an Angler’s El Dorado, New Zealand, it stopped me in my literary tracks. He had perhaps borrowed the thought from William Wordsworth’s poem “My Heart Leaps Up,” and it took me a few moments to fully absorb what they were both saying.

Wait a moment, I thought. What is he saying? What does he mean?

But on further reflection I realized that, of course, he is absolutely right.

For the man grows and evolves from the child, and without the child there can be no man at all.

Or growth.

And so it with hunting.

At least it is with me.

The very first game animal that I ever encountered was the gray squirrel.

Dad would get home from the coal mine in the evening, have his supper, and then retrieve his over-and-under Marlin 12 gauge and big hunting vest from the corner of the pantry and head up Grassy Spur or Brewster Hollow or Stoney Ridge. Sometimes he’d return with a rabbit or two, and on rare occasion even a grouse.

But he always managed to bring home squirrels.

Oh my, they were delicious the way Mom cooked them. She would first parboil them in chicken broth until they were exquisitely tender, then dredge them in finely-sifted and perfectly-seasoned flour and fry them up in her big cast-iron skillet to a buttery crisp.

The gravy she made from the drippings and the biscuits she baked in the big coal stove still send my memory into fits of epicurial splendor. I can hardly bear to discuss her green beans cooked all day and all night and then all day again in Grandma’s old Dutch oven, or her baked apples or butterscotch pies.

And now, after these many decades spent hunting on my own for game both big and small, I realize that it has all grown from those first childhood experiences with squirrels.

I was only four when Dad took me on my first squirrel hunt. When we heard a squirrel squacking up ahead of us in Brewster Hollow, Dad told me to sit down at the base of a big hickory tree. But as he eased away up the hollow without me, I began to realize just how big and daunting the woods can be when you’re small, and I finally called to him loudly, in a voice I hoped he would hear, “Hey Daddy, I’m coming—wait for me!”

He never got that squirrel.

By the time I was seven I was perfectly at home in the woods, and Dad had given me a shotgun of my own. He kept a strict and loving eye on me when I carried it and would not allow me to load it until we were sitting together in the woods watching for game.

I took my first squirrel with him when I was seven, and by the time we moved from Virginia to Tennessee, I was hunting all on my own. And though I occasionally managed to rustle up a rabbit or a grouse, my primary prey was always squirrels.

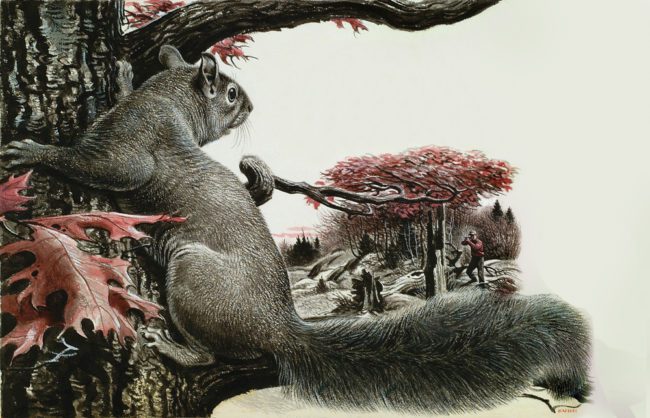

Illustration: Bob Kuhn/The Remington Collection

Squirrel hunting is a wonderful way for a fledgling hunter to learn his craft and then his art, whether that hunter is still in single digits or well advanced in years and only now discovering the enchantment. And though over the years my focus has progressively shifted from squirrels, to deer and bear and elk and all manner of winged things from Alaska to the Atlantic coast, from time to time I still return to those furry little tree creatures of my fathering childhood.

Whether with shotgun or bow or rimfire rifle, I have always taken great pleasure in this most foundational form of hunting. There’s something blissfully pleasant about feeling the weight of a full game pouch pressing into the small of my back.

But alas, there came the day late last fall when I was forced to turn my hunting attentions elsewhere, to a new and unfortunately, necessary technique—when I found myself recovering from a sudden and surprising journey to the very outskirts of the Eternal.

As a result, my cardiologist had temporarily forbidden me from shooting anything with heavy recoil or pulling my heavy bow, lest I negatively impact the most excellent work he had so artfully performed deep inside my chest.

So I decided that perhaps it was time to delve into the world of pellet rifles.

I made my way over to the local gun store and laid down a couple of 20s for an introductory air rifle, just to get the feel. It shot tolerably well, and I was soon sending an empty water bottle bouncing across the back yard along the edge of the woods. Before long my curiosity drew me ever deeper into the question of just how fast and accurate these sorts of guns could be. So I bit the proverbial bullet and decided to order myself a sure-enough, tricked-out pellet rifle.

My research finally led me to Gamo air rifles, and I settled on their Whisper Fusion Pro for its speed, accuracy, and quietness. When the new gun arrived, I tore into the package like it was a special toy for a reborn child, for that’s precisely who I was.

I had chosen the .177 caliber instead of the .22, but for no particular reason. It came with a matching 3-9 x 40 scope that was remarkably clear. The next morning I set up my Lead Sled and began tuning the gun.

I quickly discovered that this was a truly superb weapon that, of course, demanded the same rigor and attention-to-accuracy and safety as any other firearm. I had ordered a first-timer’s array of pellets of varying weights, shapes, and constructions, and by lunchtime I had settled on Gamo’s Red Fire pellets with their diamond-shaped, hard polymer tip as the most consistent and accurate.

The next morning at first light, the new gun and I headed back up to the top of the same ridge where I had been walking when my heart had first decided to protest its lifetime of inattention.

I immediately found myself reverting to those same basic hunting instincts that had first begun evolving as a child up in Brewster Hollow, listening and watching for the subtle rustle of leaves and the telltale squacking of distant prey. And the squirrels were there.

At first I found myself being a little careless and shooting at the whole animal; but soon I disciplined myself to concentrating on head shots, like I always had with my 22 rimfires. Eventually I began treating the diminutive squirrels as though they were a fine big buck or grand bull elk, and slipping the shots in behind their shoulders.

It was as supremely fulfilling a day of hunting as I have ever experienced for any prey, anywhere—the indescribable pleasure of that first time back in the woods with a rifle in my hands.

By day’s end, my game pouch was pressing pleasantly into the small of my back, and I was very tired. And as I made my way off the ridge, I found myself eagerly anticipating breakfast the next morning and the blissful taste of biscuits and gravy and the savory delight of those golden crisp squirrels.

But I also found the aging man in me basking in those blissful days of childhood, hunting with my father, until I finally called to him in a voice I hoped he would hear, “Hey Dad, I’m coming—wait for me!”

Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now

Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now