From the middle of May until the first of the following March, a turkey gobbler is straight forward.

He is reliable, he is sober and sedate and reasonable. There may from time to time pass through his head erotic flashes of pleasant passages last spring, but these constitute no more than twinkles in his eyes.

Upon occasion, possibly in an excess of fond recollection, he may gobble once or twice. Perhaps this is simply to clear his throat, or perhaps it is just for old times sake. But principally throughout this period of his year he conducts himself and his business with the disciplined dignity of retired colonels in their 70s.

Retired Colonels of Artillery, with white moustaches.

Upon your first meeting with him you would unhesitantly cash his check, solicit his advice on municipal bonds, or approach him hat in hand for a donation to build the county orphanage. He looks and acts as if he were about to be elected Chairman of the Board of Censor.

Upon your first meeting with him you would unhesitantly cash his check, solicit his advice on municipal bonds, or approach him hat in hand for a donation to build the county orphanage. He looks and acts as if he were about to be elected Chairman of the Board of Censor.

And then spring comes, and on or about the first of March his behavior patterns change, and the transition of Dr. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde is by comparison a minor aberration.

Dignity not only drops from his shoulders, he uses it to wipe his feet.

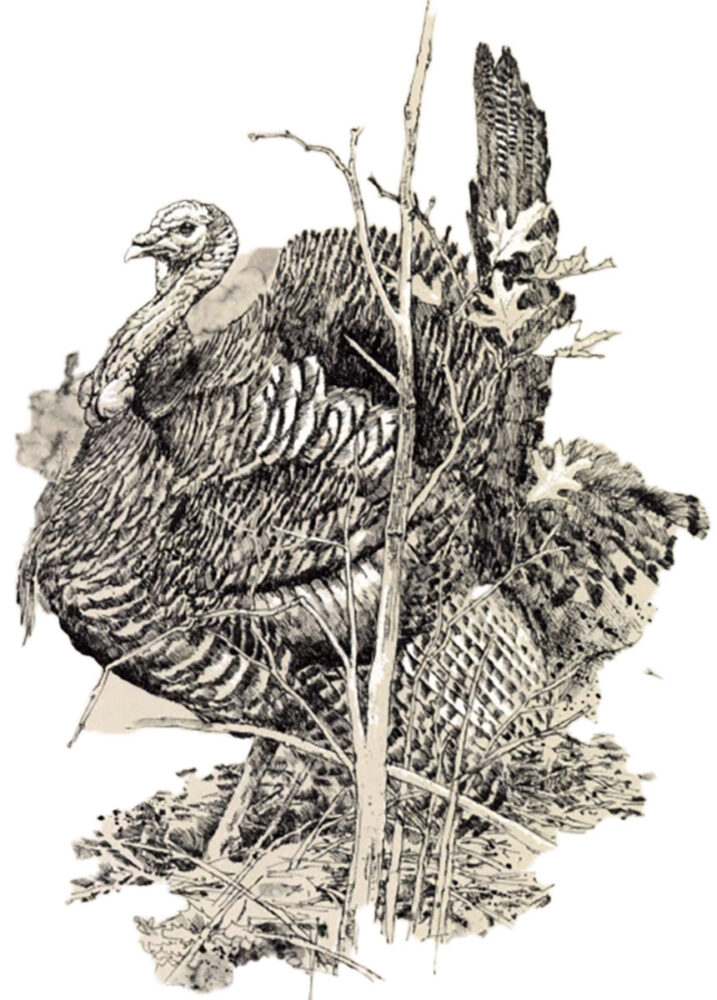

The wattles at the base of his neck swell and grow red. Instead of standing still he shifts his weight from one foot to the other all the time, as if the ground were hot. The set of his head upon his neck is different — it leans forward, looking for something. If he had eyebrows, one eyebrow would he raised all the time.

His feathers brighten and take on an iridescence they have not shown previously. He approaches the world and everything in it with the thought processes of a 20-year-old who has been at sea for 18 months.

There is in the air around him an electricity, a magnetism, an aura of bright danger — he is cocked.

He is single minded, dedicated and sole purposed. There is nothing on his mind but girls.

Girls for breakfast, girls for lunch, girls in the middle of the afternoon. Girls for tea and girls for dinner and girls before he goes to bed. And when he does go to bed he flies up and cranes his neck in all directions to pick out the roosting places of nearby girls in order that he will not take a single step in the wrong direction when getting an early start on tomorrow’s girls.

None of this interferes with his native caution or with his ingrained suspicion in any way, rather one set of emotions is overlain upon the other; or one instinct upon the other, if you prefer.

The two emotions experienced concurrently make him almost vibrate. I suspect that close to, he hums, like high voltage lines.

His sole purpose in life is lovemaking — as often as possible, as rapidly as possible, and with as many partners as possible. He begrudges the night when he must sleep and thereby interrupt the pressing business of his days.

He is cocked — all the time.

So single functioned and so dedicated is he in his purpose now, that he frequently neglects to eat. A gobbler who means it and is tending to his business (and during this time of the year it is difficult to find a gobbler who is not so occupied) will quite often lose two or three pounds during the spring — an amount that approaches 20 percent of his body weight.

He will strut and drum for as much as half an hour at a time. Strutting is technically supposed to be done to attract the female, and to do it he drops his wings until their ends drag upon the ground. I have seen turkeys who had worn off the outer four or five primaries, strutting, as cleanly as if they had been cut off with scissors. When he struts he stands the tail feathers upright and spreads them out in a fan. His head is drawn back in between what would be his shoulders, if he had shoulders, and he walks in a measured and stately manner.

I am not a hen turkey, and therefore presumably cannot adequately judge what is attractive to a hen turkey, but my private opinion is that he looks ridiculous.

A creature who is normally the epitome of slim, sleek alertness, whose feathers lie close to the body, smooth and luminous to the point of being burnished, who normally moves as if all his joints were oiled, turns all of a sudden into a clumsy ball. Every feather looks as if it had been plucked out and then glued back on, wrong side to. The neck, which had a sinuous, flowing, and nearly serpentine grace is cramped back into his shoulders in the posture of a retired 80-year-old bookkeeper with arthritis.

But there is no accounting for tastes, and he is not attempting to attract aging ex-timber markers but girl turkeys.

He drums often. This sound, which Audubon calls the pulmonic puff, defies description. It is not, to me at any rate, audible at distances beyond seventy or 80 yards. A poor approximation of its sound is to say “shut” as quickly and as explosively as you can with the tongue against the front teeth, and then say “varoom” in two syllables, with the “varoom” coming up out of the diaphragm and drawn out and resonated against the roof of the mouth as much as possible. When I hear it in the woods, I do not so much hear the sound as I feel it under my breastbone. It is ventriloquistic, pervading, and isa sensation partway between sound and vibration.

This sound is far from ridiculous. It personifies wildness and solitude and lonely places. Nothing in my experience approaches it in this respect except the wild, far off calling of geese at night, drifting down out of an early autumn sky.

A turkey even during this season does naturally have to eat a little. He is after all a bird, and the metabolic processes of a bird are far more active than those of any mammal, saving some of the shrews. There are birds for instance with body temperatures of 105 degrees when normal, and with extremely fast heartbeats. And while a turkey is not keyed to the same pitch as a warbler, he is tuned pretty high. But during this period he eats seldom and what he does eat he eats quickly, and acts as if everything he took was tasteless. He is edgy and fidgety and nervous and appears to have hi nerve ends not only exposed, but sticking out an inch or two, like antennae.

He has become not so much a bird as a psychological force. He reminds you of a good general. When you are in the company of the right kind of general officer you are not so much in contact with a man as you are with a presence. A turkey, tuned to the pitch at which he stays throughout the spring, is such a presence.

He will now stake out his own territory, his lek and restrict his movements largely to that location. He may move away some from time to time, go off to visit maybe, but it is not at all uncommon to find the same turkey gobbling on the same five acres every morning and roosting there at night, too.

He will gobble a little in the afternoon. He often gobbles once after he flies up to roost at night, but he gobbles primarily first thing in the morning. And he will begin to gobble sometimes as much as fifteen or 20 minutes before daylight, especially if he is a river swamp turkey.

River swamp turkeys for some reason begin to gobble noticeably earlier on any given morning than do hill turkeys. And from the standpoint of the hunter, it is fortunate that they do so. As clean and open as a big river swamp can be, you would never be able to get close enough to call him if he waited till daylight to begin. He would see you coming and hush, a long time before you got there, if you couldn’t go to him in the dark.

On any morning that you go to hunt you will be in the woods at daylight or preferably 15 minutes before. You will have left your car and will have walked to the place from which you intend to listen. And then you are going to prop your gun up against a tree and wait.

If you have gotten there as early as you should, the first thing you are going to hear is nothing. Nothing but you is up yet. The only birds awake are a few owls and an occasional tardy whip-poorwill that hasn’t knocked off and gone home to bed. Deer are still abroad, and you will hear them shuffling off ahead of you or boiling in herds out of thickets with all the ill-bred snorting and blowing of which they are capable. Possums and coons will still be prowling and you will hear some of these. But all of these things are night creatures that are supposed to be up. The only day creature there is you.

Just as the sky in the east begins to change from black into a steely blue-white, the owls will begin to sound off and then the cardinals, and late in the spring, the yellow billed cuckoos. These three birds make by far the most of the noise, though there are dozens and dozens of lesser bird noises in the background.

I have no idea how far you can hear an owl — one who is really leaning into his hoot and means it. I sometimes think it is like the folk song, the one that says “you can hear the whistle blow a hundred miles,” but it is a hell of along way, and early in the morning like this, most of them sound as if they were calling from across the River Styx.

It is a lovely time of the year. There is as yet not much color to the woods but there are some early hints and stirrings, mostly muted pastels or pale chalks with only two or three bright for contrast. The shrub form of Buckeye is in full leaf and flower, and the Red maple is in fruit. Both the buckeye flower and the maple seed are a bright red — a gaudy, primitive, barbaric red. Blackberry, sweetgum, and huckleberry will be in the beginning of early leaf in the understory, and witch hazel, tag alder and river birch in the middle story with both stories in pale, pale greens. All the oaks are in catkins, the long fuzzy strings that come before the leaf, and make a background of pale buff and brown. Dogwood shows occasional streaks of sharp white, and in the river swamps the yellow top makes splashes of chromium yellow.

It is a lovely time of the year. There is as yet not much color to the woods but there are some early hints and stirrings, mostly muted pastels or pale chalks with only two or three bright for contrast. The shrub form of Buckeye is in full leaf and flower, and the Red maple is in fruit. Both the buckeye flower and the maple seed are a bright red — a gaudy, primitive, barbaric red. Blackberry, sweetgum, and huckleberry will be in the beginning of early leaf in the understory, and witch hazel, tag alder and river birch in the middle story with both stories in pale, pale greens. All the oaks are in catkins, the long fuzzy strings that come before the leaf, and make a background of pale buff and brown. Dogwood shows occasional streaks of sharp white, and in the river swamps the yellow top makes splashes of chromium yellow.

Only rarely, and then only early in the year is there a hint of frost. Mostly the forest floor is a flat brown. Other than the floor, none of the colors are in masses but the catkins of the oaks. The sharper colors occur as isolated highlights scattered here and there at random.

When the owls come into full voice, just at day light, turkeys will often gobble back at them. I don’t know why turkeys gobble at owls but they do, and most men who kill a lot of turkeys have learned to do at least a presentable imitation of an owl, and do it.

Turkeys gobble primarily for girls, either to attract them or to let other turkey gobblers know they are on the job; that the situation is comfortably in hand, and that they need no help in handling anything that comes up. They can handle all the girls in hearing, thank you. But they do have a proclivity for gobbling at sudden sounds. Sometimes I think they may do it for the same reason that a man shouts in the woods. For high spirits, just for the hell of it, to hear it ring down through the trees and hear the echo come back.

Turkeys will, for I have heard them, go at sawmill whistles, at train and tugboat horns, at thunder, at owls as we said, at the slamming of a car door, at crows, and at each other. Once, on an artillery range, I heard two turkeys gobble at the sound of the first round arriving at the registration point.

The purpose in hooting like an owl (I do not really recommend slamming car doors or firing off artillery pieces) is to get a turkey to gobble who didn’t really mean to do it – finesse him into it as it were. There are mornings when every turkey in the county will begin to gobble at daylight, and will do it so much it sounds as if he were in danger of choking himself. The very next morning you can go and stand in yesterday’s footprints, as far as you can tell under identical conditions of wind, temperature, and barometric pressure, and you will stand in the midst of silence.

These are the days when you must trick him into gobbling, or surprise him into it, because until he gobbles you do not know where he is and so you cannot get to him. You want to get within 200 yards of the tree he is sitting in, gobbling, before he flies down, in order to try to call him to you from there. You want, very badly, to get there before he flies down if you can, and you have absolutely no idea of how long that is going to be. Sometimes he will stay on the limb 15 minutes, sometimes an hour and a half, and since you never know ahead of time which one it will be you need to get there quickly. Since it is possible for you to hear him at half a mile or better, it makes for an awfully interesting athletic contest conducted at daylight in the woods on calm spring mornings. The fat businessman’s quarter mile dash, with shotgun.

The reason you want to get to him so quickly is that unlike with men, courting with turkeys goes both ways, girls seeking out boys if anything even more avidly than the reverse, and your chances are immensely improved if you can get to his tree before the ladies do.

They can come in from the opposite direction of course and shut you off, but if you are quick you will be right half the time at least. Furthermore, so long as he stays in the tree and gobbles, you’ know exactly where he is. After he flies down, he is apt to move. You can tell if he is still up, or if he has flown down by the sound of his gobble, it sounds considerably muffled and has less clarity after he is on the ground.

The point is though, that until he gobbles the first time, either on his own or until you have tricked him into it, you could be within a hundred yards of a turkey in the dark, or be beyond threequarters of a mile from one and not know the difference.

A turkey can gobble only one time and give you direction. But direction is only half of what of what you need. The other necessary element you need is distance, and unless he is very close when he first gobbles, you cannot tell exactly how far away he is. Experience will help you here to a degree, but a turkey can gobble at different levels of volume. If he is still on the roost when he gobbles he could be facing toward you, which makes it sound one way, or he could be looking in the other direction, which changes the level of the sound and helps to build confusion.

It is generally considered safest to start toward him the minute you hear him, and if he will gobble three or four more times at reasonably spaced intervals, you can get his location fixed and get to the proper place to try to kill him.

All kinds of things can happen during this procedure, which in military circles is called a movement to contact.

Assuming he did not sound so far away when he first gobbled that you considered it impossible, you can, because you know the country, know that there is impassable water between you and him and so you cannot go. Or you can start and find some obstacle in your way that you were not aware of. Later in the spring, with many of the trees in leaf and the woods thickening, sound carries much more poorly. A turkey that sounds as loud the last of April as he sounded the last of March may be three hundred yards nearer than he sounds. It adds one more little uncertainty to what is often already a cloudy affair.

You can start toward a gobbling turkey who is so faraway that he does not gobble regularly enough for you to get there. This can be the most frustrating of all. You go as far as you dare, and then stand there shifting from one foot to the other. You don’t know whether to sit where you are and yelp at imagination, or to keep going in what you think is the proper direction at the very real risk of running him of for hushing him up.

The point to be taken here, though, is that whether he gobbled on his own, or whether you have tricked him into doing it, he almost has to do it more than once unless he is very close, and throughout the whole approach the contact having been established by him must be maintained by him. During this period you are absolutely under his control and are utterly at his whim.

There are some very old and very wise turkeys who gobble only a little bit. They cannot be tricked into gobbling very much and they are often silent fortwo or three days consecutively. If you can find the area one of them is using, you can then go back day after day because even if he is Silent, the contact has been partially established — but only partially. Four or five acres is a big place, even if he roosts on the same four or five acres nightly, and he can just as easily be on one side of it as he can be on the other. In such a situation he can perhaps be best located the night before. On still afternoons the sound he will make flying up to roost is so loud as to be shocking after sitting in the quiet for so long. But you must then sit there until darkness comes and lets you slip out, if he is close, and then come back at daylight in the morning.

These kind are tough. These are the kind that people spend the season with. These are the kind that if you do finally kill, you stand and look down upon with real regret because you have established such a close rapport over the days or weeks it took you to kill him.

I have never picked up one like this after killing him without a real sense of loss, a little bit sorry that I had done it, but not sorry enough to quit.

Again, while I have no logbook to refer to, nor any documents to consult, in thinking back over the years I feel that in dealing with gobbling turkeys you will kill one for every three or four that you work.

Some turkeys are just not going to come. No skill, no expertise in yelping, no combination of moves and countermoves is going to make the least particle of difference. There is no egotism in this either. I do not intend to imply that if l cannot kill a certain turkey then nobody else can kill him either, or that what is impossible for me, is impossible for anyone. I have been humbled and humiliated far too many times to have any shred of an illusion left. I have given turkey away to experts. To men I knew were experts, who tried three or four or five times and then offered them back. But I had already abandoned hope, and left it abandoned.

There just happen to be turkeys that will gobble on the roost a hundred times. Turkeys you can get to quickly, and hide from easily, and do everything perfectly, and be at the right place at the right time. Turkeys who will then fly down and gobble 300 times on the ground over a period of two hours. Turkeys who will then come to within 80 yards of where you sit and not one step farther. Turkeys who will parade and strut and drum there, and who wild horses could not drag that last 20 steps.

And there are a thousand stories about what you ought to do to kill them.

I have listened to men seriously discuss scratching in the leaves behind them with their hands, to imitate turkeys feeding. I have heard men say with a perfectly straight face that they took off their hat and slapped it repeatedly on their leg to imitate the wing flapping of a gobbler fight. You can get sacks full of advice about gobbling back at turkeys, or drumming back at them. I have heard all my life nearly, that if a turkey ever answers you he will come there eventually even if you have to sit until noon to wait for him. Maybe he will, but if it takes him that long the hell with it. I am not about to sit in the woods till noon listening to squirrels and bluejays while waiting for turkeys that may be a mile and a half off.

I have never tried scratching in the leaves either, or hitting my leg with my hat. I have never done so because I am convinced that it is going to sound exactly like a man scratching in the’ leaves with his hand or hitting his leg with his hat.

Gobbling back, I am willing to admit, may work, may be even rarely worth trying. Drumming is just barely within the realm of possibility. But I regard the large body of all this kind of advice as being in the same category as saying, “Kitty, kitty, kitty,” or standing up and whistling and calling “Here, Rattler, here.”

I am a big believer in moving. I think that unless a gobbler comes in very quickly, one of the most difficult things in the world is to firmly plant your ass under a tree and stubbornly refuse to move an inch until you have called the turkey up and killed him.

A great many turkeys will come to your calling from the roost and will then take up a regular pattern of movement, first toward you and then away, never coming close enough to shoot and never getting out of hearing, and all the time gobbling every thirty seconds or so. You know where they are every minute of the time but a fat lot of good it does you. I have upon occasion waited them out to the other end of their track, yelped once to turn them back, and then gotten up and ran a fast forty yards toward them and hidden quickly and shut up. Occasionally they will come back gobbling, and when they do stop they are forty yards closer than they think they are, and you can point out this error to. them with a Battery, one round.

On just as many occasions, I have jumped up to perform this ingenious maneuver and when I got forward and hid I did not ever hear another sound. This led me to believe that the turkey was not as far away as I thought he was when I moved, and when he saw me move he ran off. I have gotten up to move, either forward, or to get around turkeys, and have heard them go off on the ground gobbling until they faded out of hearing.

One final word on the whole subject. As much as I believe in it personally and feel comfortable doing it, and recommend it every chance I get, there are places and instances where moving is impossible.

A big river swamp is one of those places.

In the first place it is absolutely flat in there. There may be six-inch ridges from time to time and there are eight-inch depressions, where overcup oak grows. There are some striking falls of a foot-and-a-half down into tupelo or cypress ponds, but there is no other relief — none. In the fall when the sloughs dry up you can get down into the bottom of the slough bed, some six or eight feet below the normal floor, but only for this particular period of the year. Taking advantage of the terrain to move about in river swamps must be left out of your bag of tricks. In almost every case there, you can sit down and see a man walking a quarter of a mile away.

Except in exceptional instances, attempting to move on turkeys in this area is stupid. There will be all kinds of situations that arise with turkeys two hundred yards off and in absolutely plain sight and no matter how badly you want to do it, you cannot move. If there is a rule for river swamps it may be stated simply that where you sit is where you stay.

In plain fact, the mere selection of a place to hide and call from in there is extremely difficult. There are some blowdowns, of course, and some places where tangles of vines wrap around the bases of trees. After the timber has been cut, if single tree selection or patch clear cutting were used, there will be clumps of briars and some low seedlings. Yellow top in the spring will make thick clumps of foliage, often too thick, and there are some patches of palmetto. By and large, though, if you hunt in river swamps, whatever you intend to hidebehind you must bring into the swamp with you. Whether you use a roll of camouflage netting or intend to cut bushes, you had better have them with you when you go. In there, as in Macbeth, Birnam Wood must come to Dunsinane.

In plain fact, the mere selection of a place to hide and call from in there is extremely difficult. There are some blowdowns, of course, and some places where tangles of vines wrap around the bases of trees. After the timber has been cut, if single tree selection or patch clear cutting were used, there will be clumps of briars and some low seedlings. Yellow top in the spring will make thick clumps of foliage, often too thick, and there are some patches of palmetto. By and large, though, if you hunt in river swamps, whatever you intend to hidebehind you must bring into the swamp with you. Whether you use a roll of camouflage netting or intend to cut bushes, you had better have them with you when you go. In there, as in Macbeth, Birnam Wood must come to Dunsinane.

And you have to hide. Hill or swamp, in the spring you have got to do it. There is all sorts of evidence to suggest that a turkey is color blind. Maybe he is. But he can damn well tell dark colors from light ones, and he is the world’s bet at picking out motion. Picking it out at a long distance too.

Perhaps in the early fall, if a man could sit with the utter stillness of a professional naturalist, he could depend upon calling up young gobblers, remaining immobile against a dark background, and raising the gun to shoot in one motion at the last. I say maybe only because I am willing to listen to another man’s point of view, not because I really believe in it.

To go through life in the spring, dealing with old gobblers, attempting to sit out in the open and depending upon immobility to get the job done, is folly.

Nobody, nowhere, no time, is going to get away with it on anything like a regular basis.

Tom Kelly self-published Tenth Legion in 1973. He created this masterpiece of Wild Turkey literature by recording into a portable dictation machine while working in the woods. His wife Helen, transcribed his words into a book that has become the Bible of Wild Turkey hunting. The book has not changed in the past 50 years, even if the dust covers have had many different looks. Buy Now

Tom Kelly self-published Tenth Legion in 1973. He created this masterpiece of Wild Turkey literature by recording into a portable dictation machine while working in the woods. His wife Helen, transcribed his words into a book that has become the Bible of Wild Turkey hunting. The book has not changed in the past 50 years, even if the dust covers have had many different looks. Buy Now