The thought of a sportfishery for great whites tantalizes some anglers, but if it’s ever to happen, the science will have to support it.

“I want to show you something.”

I had spent enough time working for the artificial reef program at the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources to pick up on the subtle nuances of my boss Bob Martore’s moods. As I stood in his office, looking over his shoulder, he wore a tiny half-smile that usually preceded an entertaining conversation. Without preamble, he pulled up a web page on his computer. “This,” he said while tilting the screen toward me, “is Mary Lee.”

My eyes widened at the photo of a live 16-foot, 3,000-pound great white shark sprawled on the deck of the research vessel.

“That’s…a really big shark,” I muttered.

“Oh yeah,” Bob chuckled. “The Ocearch research team recently tagged her with a satellite transmitter in Cape Cod.”

Bob briefly explained that Ocearch (pronounced o-search) is a non-profit organization that captures, tags and releases great whites and publishes real-time migration data on its website. He closed the photo to show a map of our East Coast.

“Take a look at where she’s been.”

A bright orange line marked Mary Lee’s path that ran southward from Cape Cod, hugged the coast of South Carolina, then passed within mere miles of our artificial reefs near Charleston before continuing on to Florida.

As part of my thesis on fish communities on offshore reefs, I had planned to dive on those exact sites near Charleston the next morning, and according to the map, she had recently reversed direction to head north again from Florida. Given her current location and rate of travel, she could be prowling around our dive sites by the time we hit the water.

So of course I asked the obvious question: “Would I automatically pass my thesis defense if I included video of a great white shark?”

I was both disappointed and relieved that we didn’t encounter the fair lady herself, but most people would, understandably, have some misgivings about diving in Mary Lee’s chomping grounds. They think about sharks and automatically hear the telltale cliché music while the dorsal fin rises menacingly out of the water.

In reality, great white sharks have far better things to do than prey on innocent swimmers. But despite our decades-long fascination, we’re only just starting to understand them as a species and as a source of recreation.

When it comes to bad press and movie dramatizations of sharks, most people immediately think of great whites. With eyes that are black pinpricks against pale gray and white bodies and fearsome jaws frozen in a toothy half-smile, it’s no wonder that people look upon these huge predators with trepidation and respect. They have been sensationalized in television documentaries, inspired awe and terror with their sheer power and have starred in horror movies as oversized animatronics.

Scientists, fishermen and the general public all have differing opinions and perspectives about great white sharks. Some seek to study them, others want to catch them and still others waver between the two extremes of blissful ignorance and obsessive fascination.

My fellow marine scientists and I know precious little about the behavior of great whites – how far they travel and how they reproduce. That’s where we turn to Mary Lee.

Ocearch’s Global Shark Tracker program has tagged and monitored more than 40 great whites around the world and provides real-time migration updates, which is how Bob and I found out about Mary Lee’s habit of paying semi-regular visits to our dive sites.

Great whites rarely stay in one place for long, traveling hundreds of miles along the East Coast, across ocean basins and around South Africa and Madagascar. They range from cold temperate to warm tropical waters, following the migrations of seals and sea lions, and hunt their prey visually, using their dark gray backs to blend in with the surrounding water before rocketing toward the surface and launching their bodies completely into the air in a brute-force attack.

As a lifelong sport fisherman, I also understand the appeal of great white sharks as perhaps the pinnacle of trophy fishing. After all, who wouldn’t want to match wits, strength and cunning against one of the ocean’s most feared apex predators? However, their vast migrations make it extremely difficult to manage a recreational fishery.

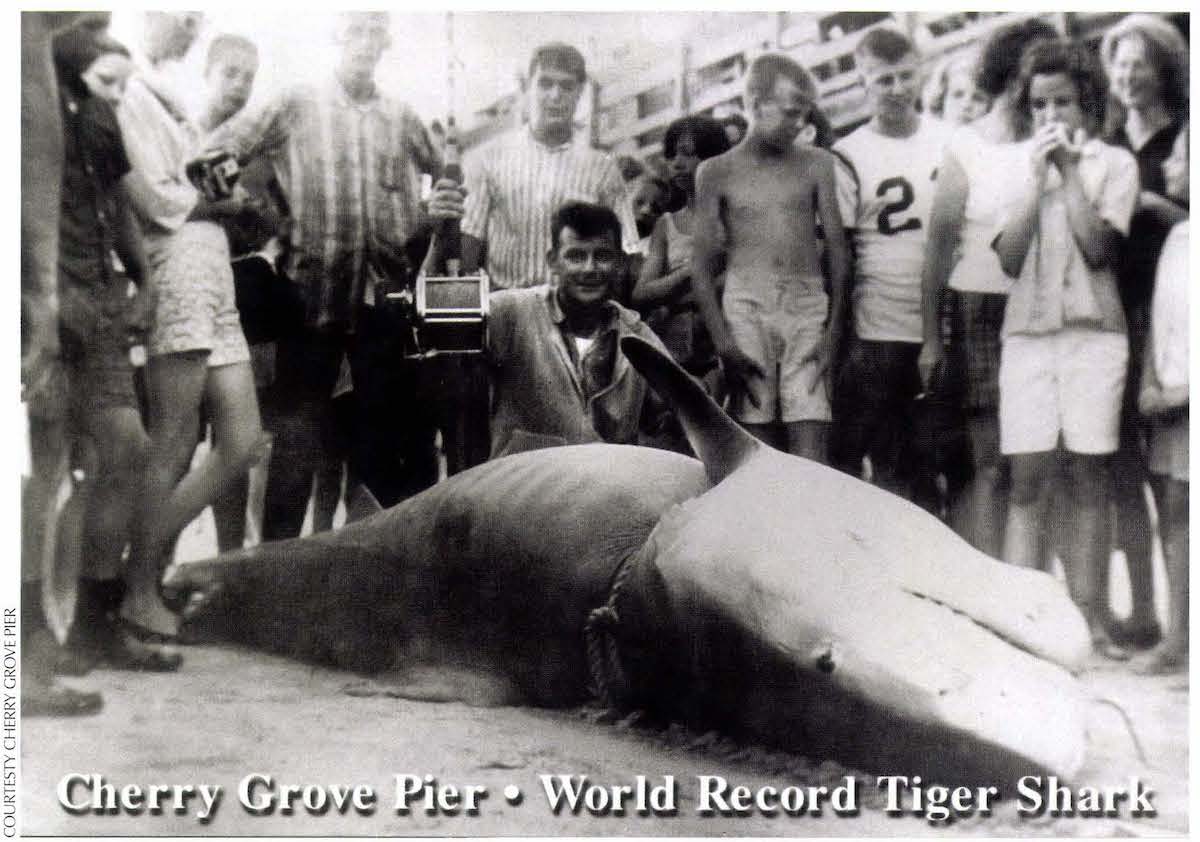

Hooking a great white relies on being at the right place at the right time or stumbling across a nursery habitat. David McKendrick landed the world record great white, a 20-foot female, off Canada’s Prince Edward Island in 1988 while she fed on a whale carcass. In December 2013, a U.S. Marine hooked a nine-foot juvenile by accident on a beach in southern California and played the shark for nearly a half-hour before safely releasing it in deeper water.

Scientists tag great white sharks in order to obtain data on migrations and nursery habits – information that will enable marine biologists to gain a better understanding of these fascinating creatures.

Accounts such as these are few and far between and, as of this writing, they’re downright illegal. Great whites are listed as “Vulnerable” under the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and enjoy more local and international protections than any other shark species worldwide. In the U.S., great whites are federally protected from both commercial and recreational fishing. The Marine in California knew the laws protecting great whites and immediately released the juvenile once he realized what he had hooked.

For the sport fishermen reading this story, please bear with me. My goal is not to crush your dreams of catching the world’s most famed shark species. But like any other fishery, great whites must be managed scientifically. One-third of our oceanic shark species face extinction from overfishing and the morally reprehensible shark-fin industry, where people slice the fins off live sharks and toss the bodies back into the water to die a slow, painful death. Such wanton waste risks ruining the sport of shark fishing for those who seek to enjoy it responsibly.

The first step for establishing a fishery is to learn about the species’ life history. By tagging great whites such as Mary Lee and following them throughout their lives, we gain knowledge about their migrations, their generation time and their nursery habitats. Only then can we predict population sizes, how many individuals we can sustainably remove through fishing, and then assign permits and licenses accordingly.

And while great white sharks are off the table for now, fisheries already exist for a multitude of other shark species, from the smaller inshore species such as sandbar sharks and bonnetheads up to the sleek, agile shortfin makos that patrol the open ocean in the North Atlantic. Anglers and scientists already work together to manage these fisheries by recording biological information such as each shark’s size, health and location of capture when the boats return at the end of the day, and it’s not too much of a stretch to envision the same partnership for a great white fishery.

In the meantime, people still enjoy great white sharks recreationally by cage diving along the fish’s migration routes. David Shiffman, a renowned shark biologist and personal friend, went cage diving with great whites in South Africa, showing that the scientists can join the fun, too. The bravest souls ditch the cages entirely in favor of free diving with the sharks using nothing more than a wetsuit and snorkeling gear. Photos of snorkelers grasping the sharks’ dorsal fins and gliding with them in peaceful companionship have elicited strong responses of shock, awe and reverence across the Internet.

As for Mary Lee, she still frequents her favored fishing grounds along the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida where her life revolves around the simple, primal instincts of survival, with no time or concern for the scientists, fishermen, and lay people who study, revere or fear her. Perhaps our paths will cross on a dive someday, and I will count on her regal indifference as I share the ocean with her as a humble guest in a queen’s domain.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

Read on as some of the sport’s most talented writers recount their personal memories of catching bass, trout, bluefish marlin, tuna, and more. Explore the Pacific with Zane Grey, as he fights a 1,000-pound blue marlin, or listen as A.J. McClane explains just what it really means to be an angler. Take a step back in time when you read Ernie Schwiebert’s tale of fishing a remote lake in Michigan, when he was still only a young boy. Each of these stories, selected because of its intrinsic literary worth, reinforces the unique personal connection that fishing creates between people and nature. Buy Now