About that time it dawned on me that we had probably made a bad decision!

Many years I owned and operated several huntingpreserves.in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Now that I’m retired, my wife Rita and I spend our Winters in Rincon de Guayabito, a small resort village not far from La Paz on Mexico’s west coast. From Tioga, Pennsylvania, we pull a 31-foot Coachman trailer and my 15 1/2-foot Starcraft boat some 3,100 miles over the eight-day trip. We usually stay about five months, enjoying the balmy weather and fishing for yellowfin tuna, sailfish and dolphin.

I knew that marlin weighing up to 1,500 pounds had been taken in the waters outside of our Village, and during our visit in 1982, I thought it Would be quite a feat to catch one of these monsters from my own boat.

One day I asked the local fishermen to bring me some black skipjack, or chula, and they came back with several four-eight pound fish. After stripping out the bellies, I cut the fish into 12-inch chunks, inserted a #14 hook in the from portion and sliced the back part to fashion a tail of sorts that would flutter enticingly when pulled through the water.

The next morning, I headed out to where I had seen marlin caught before, but I ended up trolling five hours without a strike. On my way back, I figured that I’d try again in the morning, particularly when I found two more chula lying on the ground by my truck. That evening, Rita and I were playing cards with Stan Sutton and his wife Sally, and it was only a matter of time before the conversation got around to fishing and then to my quest for a marlin. “You need a fishing partner?” Stan asked when I told him I was going out again the next day.

“I’ll be glad to take you along,” I replied, “because if we do hook one, it might be a long time trying to boat it -maybe all night.” Little did I realize how prophetic my statement would prove to be.

By 6:15 the next morning, we motored past the small island off Rincon, on our way to the marlin grounds 15 miles offshore. Once there, we baited up my old #9 Penn reel along with a heavier rod and reel that I’d borrowed from a California fisherman. We began trolling about four or five miles per hour, our baits skipping along about 60 feet behind the boat.

A few hours later, a dorado in the 40-pound class jumped over the top of one bait, but never came back. Just after that a sparkplug started missing in my 35-hpoutboard. (Gas in Mexico is a lower octane than gas in the U.S. and often causes carbon problems.) The motor soon quit, so I got out some tools and began replacing the plug. The boat bobbed up and down on the big swells, while the baits drifted into the depths.

I installed the new plug and pulled the starter rope, but before we could get underway, one of the reels turned a couple of clicks. Before I could get to it, the reel clicked six or seven more times, so I pushed the gas to full throttle. The old Penn screamed as more than a hundred yards of 100-pound monofilament flew off the reel.

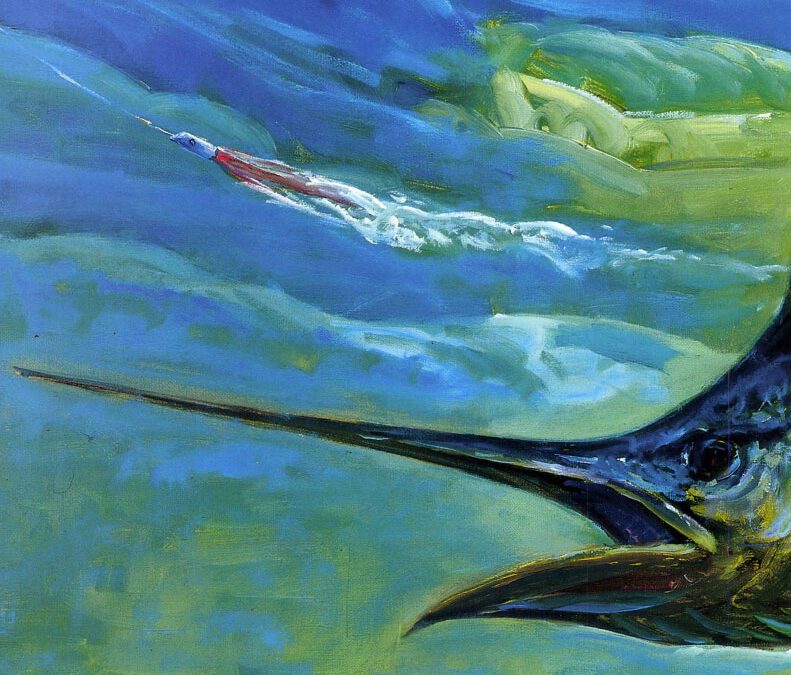

Our eyes were riveted on the foaming wake behind the boat. Suddenly a huge fish torpedoed across the waves, its steely blue sides glistening in the sun. The fish leaped high above the water and Stan yelled, “My God, we’ve got a blue marlin!”

I had stopped the boat by then and we had our hands full trying to fight a fish that looked to be nearly as long as the boat.

We were excitedly anticipating the marlin’s next jump when the biggest dorado I had ever seen — a fish that probably weighed 75 pounds! — leaped out of the water in front of us. And right on its tail was our marlin, trying except for 200 feet, and the marlin never broke the surface again, choosing instead to remain far below the waves.

I looked at Stan as the marlin towed us ever farther out to sea. “How long can he keep this up?” I asked.

My friend raised his head and, looking a little tired after his half-hour turn of holding the rod, replied, “He’s slowing down quite a bit. How long have we had him?” I checked my watch. We had been fighting the marlin for over four hours.

As I took over the rod for my 30-minute turn, the marlin sounded and the line began disappearing off the reel. I set the drag tighter and tighter. The rod-holder I was wearing started slipping up past my belt and my shoulder harness wasn’t doing any good, so I decided to discard the rig. Unable to put pressure on the fish, I simply positioned the rod across the gunwale while the marlin plunged deeper and deeper.

“There’s less than 150 yards left,” I announced. “Let’s get that other rod and reel fastened to this outfit, then we can just toss this one over the side when the line runs out.”

Stan quickly fastened the other line to my old #9 reel. I only had about 80 feet of line, but the marlin was slowing down because I had the drag screwed tight. When the fish finally stopped, less than 50 feet of line remained on the reel.

My next turn was the most exhausting half-hour of my life. Just holding onto the rod put a tremendous strain on us, so we decide to reduce our turns to 20 minutes each. When Stan took over, he just sat there with the rod bent in a full arc and the line stretched as tight as the strings on a banjo. I jokingly asked him what he was doing and Stan turned to me and said, “Omar, I think I’m fishing.”

When my turn came again, both of us tried to lift the rod in hopes of budging the fish slightly and getting at least a few feet of line back. Nothing doing — the rod would spring right back, with absolutely no action visible on the tip.

Stan sat down wearily and with a thoughtful look on his face, said, “There’s something wrong here. We haven’t felt him on the line for nearly two hours.”

I remembered a story I’d read a few years earlier about a man who had hooked a marlin that had sounded and then died. Could our marlin be dead 900 feet below? The only way to find out, I thought, was to see if we could move the fish.

I started the motor and put it in gear, then both Stan and I held onto the rod. “Easy, easy,” he yelled. “I can’t hold it!” I strengthened my grip on the butt, certain the line would break at any second. The boat seemed to be moving forward and sure enough, the line started to angle away into the water. Cautiously, I pushed the throttle ahead even more, but after 15 minutes we realized we hadn’t gained even a foot of line.

Next, we tried putting the motor in reverse, but we quickly dropped that idea when the waves began splashing over the transom. After that we went forward again for about 10minutes, but without making any headway. Finally, we decided to turn the boat and head back toward the angle of the line. Coming out of the turn I gave the motor more gas and we picked up about 30 feet of line — then more and more over the next hour until the reel was again nearly full.

Suddenly Stan hollered, “The reel won’t turn!” It had locked up, its gears burned out.

“We can’t lose him after getting so close,” I yelled back. “Let me have the line.” I grabbed the monofilament with my bare hands and strained against the fish until I thought my fingers would be cut off from the line buried in my palms. Ever-so-slowly I piled up yard after yard of line in the boat. Soon we could make out a white shape rising up through the water. It was our marlin! We had finally outdone him — after seven hours and 15 minutes!

By now the sun was beginning to set, and we were at least 30 long miles from camp. Still, we felt a celebration was in order so we split our only beer. It wasn’t champagne, but it tasted just as good. We then turned our attention to towing the giant marlin through an ocean that was getting increasingly rough. I looked at the fish and felt like Spencer Tracy in the movie, Old Man and the Sea. I didn’t see how we could ever get him in the boat, but we had to try.

With both of us standing on one side, we began pulling on the marlin until the boat was dangerously level with the water. We backed away and heaved again, and slowly the fish’s head and part of its upper body slipped over the gunwale. But no more. We couldn’t move it another inch. I grabbed the rope that I had tied to its tail, pulled as hard as I could, and suddenly the huge fish slid right in, pinning my knee against the back seat.

“He’s breaking my leg,” I called out. “Pull, Stan. Pull!”

“I can’t! If I let go, he’ll come back on your leg even more.”

There was no way to move the fish, so with a wrenching twist, I managed to pull my leg free. My leg hurt, but it seemed in one piece. I was thankful that I didn’t have a serious injury.

About that time it dawned on me that we had probably made a bad decision! All that weight in a 15 1/2-foot boat, and not properly balanced at that, allowed the waves to wash in over the stern. It was impossible for us to lift the fish backout of the boat. How much water could we take on? With dusk creeping in, we knew we were in a tight spot, with no one to help us on this lonely stretch of ocean.

Our only chance was to head toward shore — very slowly. The first wave broke over the boat and my eyes met Stan’s for a brief moment. We looked away quickly, each with our own thoughts. It was pitch-black by then and the ocean was getting even rougher.

We had a bad time for an hour so, then luckily the ocean smoothed out and I was able to inch the throttle forward. We didn’t have a flashlight, but we did have two packs of matches, and every once in a while we would strike one to read the compass heading. With so much weight in the little Starcraft, it was difficult to maintain a straight course.

Finally, we saw lights on the horizon and knew that we would arrive at the camp within an hour so. When we passed the small island off Rincon, our spirits rose even higher, even though we had taken in a lot of water and had no way to bail it out.

As we neared the beach I shouted toward shore, asking for someone to blow the camp horn. The horn sounded, and soon the beach was filled with eager hands who helped pull our boat onto the sand. It was 8:30 — more than 14 hours since we had headed out.

With the help of five other men, we dragged the fish over to the weighing rack. It was built of four-inch poles, sturdy enough for hanging dorado and sailfish, but as we pulled up the marlin, the rickety structure creaked and trembled. Everyone moved back, expecting the rack to topple, but somehow it held together. The marlin measured 11 feet 5 inches from tip of bill to fork of tail and weighed 504 pounds. After much picture-taking, we removed the entrails, salted the interior and left the fish to hang overnight.

The next morning, still exhilarated by the previous day’s adventure, we went over to study our catch in the bright Mexican sunlight. The marlin seemed even bigger than before, and I began to realize the magnitude of our accomplishment.

Then, with the help of many hands and sharp knives, we set about reducing the huge marlin to pan size. That evening, we had a fish fry for 67 people. We ate the fish deep-fried, barbecued and baked, and found it delicious no matter how it was prepared.

We’ll head back to Mexica again one day with our Starcraft boat and the old #9 reel. With any luck, the spark plug will foul up at just the right spot in the ocean on top of a real big fish — and we will wait with relish for our lure to drift down.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2000 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.