I first went there when the moon was new and the heat of summer was past and the sparse rains had come and the bush gleamed with flecks of jade and emerald and the tiny dots of multicolored wildflowers. It was the time when the bull kudu were running with the cows, and oryx and wildebeest and hartebeest filled the plain. The leopard slunk and the cheetah skulked and they, like us, took their just measure of the life upon the veld so they might also live, and all was right with the world.

Rooikrall is the home of Joof and Marina Lamprecht. Many years ago it began as a dream in the minds of two youngsters. In time, the dream firmed into a reality and with decades of hard work became a thing of substance, that grew until it now sprawls across 80 square miles of Namibian bush, a couple of hours drive from Windhoek. Its arid, rocky ground is lightly covered with sparse grasses, hookthorn, kudu bush and the low, flat-topped acacia that spread across the plain like thunderheads on a summer’s eve. Boulder-studded kopjes dot the landscape and provide vantage spots for glassing game.

Being as it’s closely guarded by the Kalahari, it’s not especially welcoming of domestic livestock. But it is extraordinarily welcoming to the wild folk who have, for millennia beyond reckoning, evolved in her harsh environs. There is scarce live-water, even in the wettest of seasons, and the Lamprechts have invested deeply in wells and pipelines. Now, waterholes dot the landscape and wild game flourishes across the width and breadth of the massive holding.

According to plan, the farm is now reverting to the care of Mother Nature and going back to bush. The family concluded some while back that it was better to work with Mother Nature and allow controlled hunting on the property than to battle her in a vain effort to farm. And, as always, when man stops meddling, nature is quick to reclaim its own.

On the farm they built their home, a sprawling two-story, multi-bedroomed house with balconies overlooking the surrounding bush. It was built of stone and wood and thatch around a centrally enclosed courtyard to prevent nocturnal intrusions by lions and leopards. Inside, it’s cool and shady and filled with Africana of all kinds. Outside, you may well see game slipping through the bush from any of the balconies.

The home could have well served for the prototype for the house in the movie based upon Karen Blixen’s book. Now it also serves as a base for guests who come to hunt with their safari company.

For the past several years the Lamprechts have been hosting plains game hunts under their Hunter’s Namibia banner. A second, similar dwelling in the far reaches of the farm now serves as headquarters for their bowhunting operation. It anchors the shore of a large lake that the couple also built.

Today, when we fantasize of Africa, we most often dream of pristine wilderness, but most of the continent’s known history is one of farms and ranches. It is the never-ending story of man’s lust to conquer, to tame and to convert everything that he finds to serve his own needs and wants.

Theodore Roosevelt’s timeless book, African Game Trails, was first published in 1910. Yet in this classic story of his safari in east Africa, he recounts time and time again his meetings with farmers and settlers, and occasions when he hunted on private land-holdings. Most of Africa has been settled for a long, long time!

Although they call Rooikrall a “game ranch,” the term hardly applies. All of the game animals are indigenous to the farm. They were born free and live their lives as free as the winds of the nearby Kalahari.

Most years Joof and Marina come to the U.S. in January to take in the show circuit and promote their Hunter’s Namibia. I made their acquaintance several years ago at one of the shows and over many such meetings, became friends. Eventually, the couple invited me to see their farm, do a little hunting and see a side of Africa that I had never seen.

At the appointed time, I packed up my new rifle and shotgun and hopped a Delta flight from Atlanta to Johannesburg where I overnighted at Witwater, the guest house that I use when passing through Johannesburg. The next morning I took off for Namibia on South African Air. Marina waited in the little airport on a cool, clear morning that made a sweater welcome, but unnecessary by noon.

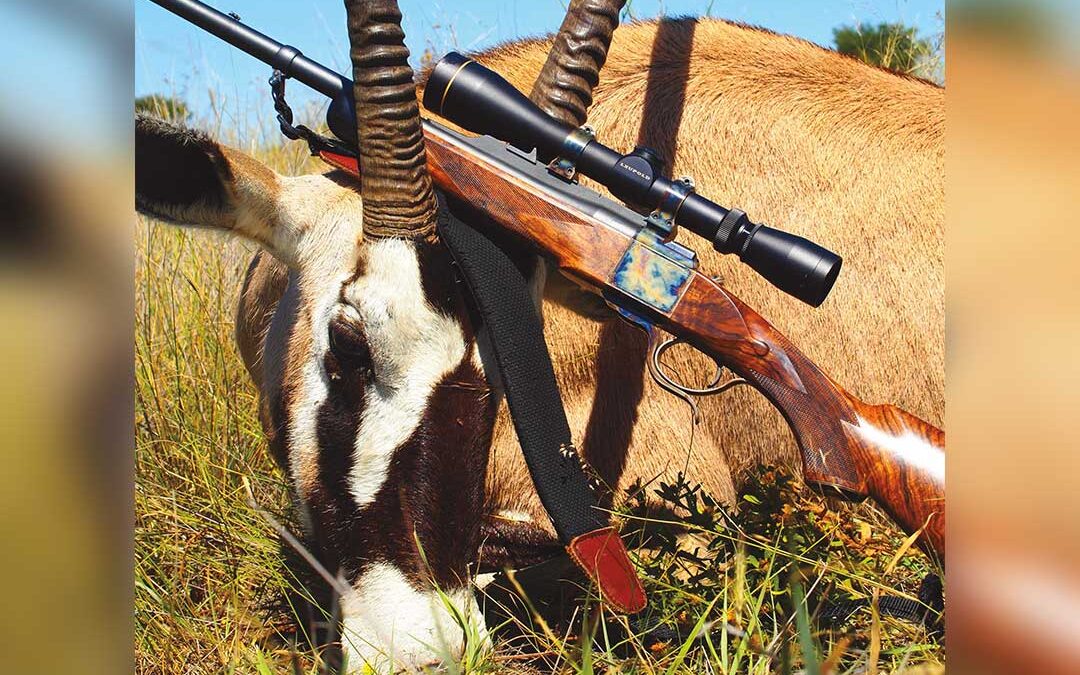

Just before leaving home, I had received a newly minted Dakota #10 in 7×57 caliber. Most folks prefer a slightly larger caliber for African plains game, but the little Dakota was so stunningly beautiful and so handy that I couldn’t resist taking it. Considering the storied history of the cartridge in African lore, I reasoned that the little 7×57 should be adequate for all plains game save eland, which I had no intention of taking. And so it proved to be.

Joof spent a couple of days showing me around the farm and then, having other business to attend to, turned me over his staff PH, Johnny Gohocnobeb, and Johnny’s tracker, Illonga. This turned out to be a great turn of good fortune, because we instantly “knew” each other. All three of us of us grew up as hunters. Not for sport or business, but of necessity. No doubt, their childhood necessity was of a much greater urgency than mine, but we all knew how to hunt on a “first-person” basis and on the most intimate terms. Hunters are hunters, and despite the cavernous divide between the three of us in terms of language, culture and geography, we soon discovered that the base of our understanding was very broad, and miscommunication was not an issue.

As always in Africa, days ran upon days of adventure. On the first day we happened upon a beautifully long-horned cow oryx and since Marina had put in an order for a good “table oryx,” Johnny and I slipped over the side of the Land Cruiser, and made a short stalk. At the shot, the old girl took off at a dead run and after about 40 yards, got her feet tangled and tumbled like a rabbit, flipping head-over-heels in the dust. She was stone dead when we got to her. The little Dakota 7mm had worked just fine, and it was a performance that would be repeated often over the next few days.

Gemsbok, wildebeest, hartebeest and waterbuck would fall in turn. I wanted a kudu, but the elusive bulls lived up to their reputation, aided by the fact that they were wandering constantly in search of receptive cows. Had we been in a closed space, this would have been an advantage, but the farm is huge and the bands of kudu cows were widely dispersed. Since the rut was just beginning, the bulls would quickly check one group of cows and leave just as quickly to find another herd.

On the third day I discovered that Johnny and Illonga were perhaps the best trackers that I have ever had the pleasure of working with. Just as the sun was creeping over the horizon we found a good kudu bull. Foolishly, I rushed the shot, centered an inch-thick acacia limb and peppered the bull with shrapnel. It was an unpleasant necessity, but the two men tracked the bull for the rest of the day to make sure it was not seriously injured. It was as nice a job of tracking as I have ever seen, leading us for a couple of miles down one side of the farm and another three into the adjoining farm after the bull jumped a fence.

On the following day we were again looking for a gemsbok to grace Chef Hennok’s table. It was sunny, nearing midday and as is often the case around that time, a hot, unstable wind was constantly shifting and swirling. Johnny, Illonga and I were slipping around the base of a large kopje where we had glassed a herd containing a big bull. The bush was quite thick and visibility only about 30 or 40 yards when the wind once again shifted just wrong and the animals spooked.

Johnny motioned for me to follow and ran about a hundred yards through the dense brush to a long narrow opening that ran up the hill in the direction they had fled. We didn’t get a shot at the gemsbok, but discovered that in the confusion they had disturbed a huge bull eland that piled over the top of the little hill in panic and caromed down the same little clearing.

To the considerable dismay of all, the bull’s run was blocked by three puny human creatures, two black, one white, who broke into their own panic run trying to get out of the way of the two-ton calamity that bore down on them at full speed. At the last second we dove into the bush, and managed to miss the “train wreck” by a couple of yards. Such is a day in Africa.

A couple of days later we almost had another collision when the three of us stepped into the middle of a family of five cheetahs dining on a freshly killed duiker. The tom nearly bowled me over when they sprang from the bush. The hair still stands on the back of my neck when I think about it! I would have gladly taken a shot at the big guy, but he wasn’t hanging around for any such nonsense. The last we saw of them was when they crested a kopje about 300 yards away and paused briefly to look back.

From the moment I arrived until the morning that I left, there was nothing of the mundane, nothing of the ordinary. That ‘s the way Africa is. From the giraffe that discovered us crouching in a leopard blind, peering, impossibly long-necked, over our carefully constructed hide, to the ever-present jackals, or the leopard we spotted unperturbed, watching us pass from a distant waterhole, nothing was bland. Not the cheetah stalking warthogs, nor the sand grouse that we shot over a tiny waterhole in the bush. Nothing was commonplace.

Not once during my time at Rooikraal did I see the contrail of an airplane scribbling graffiti upon the sky, or feel the crush of others of my kind, or hear a human sound that was not of our own making.

The last dawn broke just as all others before, clean and cold and crisp and filled with the vocal musings of the creatures large and small who own this beautiful country. The sun rose as it has from the beginning of time, blood red against the distant blue mountains.

Johnny and Illonga and I shivered against the cold breeze that drove across the veld from the Kalahari to graze the top of the kopje where we sat glassing for kudu. A jackal hunting his breakfast stole around the base of our little mountain. A herd of kudu cows filed along a distant tree-line beneath the rising sun, perhaps three-quarters of a mile to the east. Try as we might, we couldn’t conjure up a bull in the herd. A band of red hartebeest ambled slowly across the southern periphery of our little world, and three ostrich moseyed toward cover as the sun climbed and the sky turned gray, then red, then blue. But no kudu bull came.

In time, the air began to warm and movement slowed to nothing. As we climbed down from our rocky perch, Johnny asked if I was ready to call it quits. Or would I rather take one more drive? Perhaps around a small waterhole that I hadn’t seen?

I knew that the odds were slim, but then it might be a long time before I was privileged to return. And what could be better than an early morning drive in the Namibian bush?

Illonga drove as Johnny and I stood in the back of the Cruiser for a better look over the bush. Still, it was Illonga who saw the bull kudu first, standing stone-like, watching from the thornbush as they so often do. He was watching us as the Land Cruiser crept along a couple of hundred yards from his hiding place. There was nothing of him visible but his head, which was framed like a portrait, his chevroned face and spiral horns spotlighted by the rising sun.

Johnny and I tumbled out the far side of the Land Cruiser into waist-high grass as Illonga continued to creep along in the direction we had been traveling. The bull never noticed the motion in the grass and never moved, but after slipping about 50 yards, we ran out of cover. I knew that he was too far. Try as I might, I could not see even the slightest outline of his body through the scope, and had all but made up my mind to pass up the shot when the crosshairs steadied and hung upon a spot, more sensed than seen, where a tiny patch of gray was exposed about a foot below his white chevron.

I was as surprised as my two companions when the shot broke. It was clean and slick and unexpected and coolly perfect in the way that it sometimes is when we dream that we are doing something that we are incapable of doing, and when the bullet slipped beneath his chin, he simply disappeared from sight.

Johnny Gohocnobeb (right) and his tracker Illonga with Matthew’s big kudu.

I thought that I had missed, but when we reached the spot in the bush where he had been standing, he was lying with his legs tucked beneath him and his chin upon the ground and the ivory tips of his great spiral horns were reaching for the sky. And once more all was right with the world.

And so it is in my heart of hearts when I remember Rooikrall. To one born a hunter, it may well be the finest place on the planet. I can honestly say that I know of no place better. And with luck, I will return. To hunt again with Johnny and Illonga. To watch the waterbuck from the balcony outside my room as evening blankets the bush and the doves are silenced by the night. To dine once again at Marina’s table. To once again climb the lantern-lit stone stairs to my room where the glow from the corner fireplace breaks the chill. To breathe the cold, clear wind that blows from the Kalahari and watch from the slope of a kopje as the leopard and cheetah and jackal hunt as if their lives depended on it.

In her book, Karen Blixen mused, ”If I know a song of Africa, does Africa know a song of me”? I too, know a song of Africa. But Africa does not answer to mere humans. She only questions. And I, too, wonder if she knows my song. And if she will know me when I return.

IF YOU WANT TO GO

For more information email: mailto:hunters@mweb.com.na or visit www.huntersnamibia.com.