A boy’s dog named Soc finally proves his worth as a gundog by flushing pheasants for the boy and his uncle.

That first spring together evolved into a long, hot summer, seemingly endless for a boy hankering for his first pheasant season. Sweating through chores, I often lamented the expanse of my promises to Uncle Harry so I could have a dog, and most days I wanted to scoop up summer and bury it behind the barn with the rest of the roadkill. Cleaning cow stalls of a winter’s worth of dung, I ached everywhere. Add to it the scents wafting from the chicken coop and pig sty where more layers of crap awaited my shovel, and it was the summer of my discontent. A season of shoveling, milking, slopping, plowing, planting and weeding cured any delusions I had of becoming a farmer. If not for my dog, Soc, I never would’ve made it.

I knew he had hunt in him right away. Nothing moved that he didn’t stalk and point. Birds, butterflies, rodents, chickens—even cows caught his curiosity, despite some too-close-for-comfort kicks near his head. My favorites were the killdeers that lured him from their nests with broken-winged deception. Chase, creep, point, repeat . . . Soc let them fool him at first, but he was no bird’s dupe for long. Ignoring a flapping killdeer one day, he circled back and surprised a hen pheasant to flight.

I figured I might have something then. Maybe he would live up to his namesake in more ways than one, even if I did have to run a country mile sometimes to catch him. Flush a hen, miss a rooster, same difference. Soc would race out of sight after either like a grass fire in a drought. Hardheaded as a woodpecker, he would never be known for steadiness to wing and shot.

By the time frost was on the pumpkin, our hopes were high given all the roosters we had observed popping up like flares in the fields since spring. Even the old mail carrier, more taciturn than not, noted the numbers and lingered one day at the mailbox to regale me and Soc of his bird counts.

“I haven’t seen nothing like this in years,” he said. “Not since Ike . . . maybe even better than then.”

“Who’s Ike?” I asked.

“I hope you’re teaching that dog better than they’re teaching you in school, boy.” Putting mail in my hand, he started down the road when a big cock dashed from the ditch and scooted past him.

“See what I mean?” he yelled.

I went hungry in September spending my lunch money to buy shotgun shells at the hardware store. Thirty-five cents bought me two 12-gauge Peters number fours, one-and-a-half-ounce “greenies” we called them, a good load for big, hard-flying roosters.

By opening day, I had nearly half a box to dump into my vest pockets along with a thermos of hot coffee and a pickle and ham sandwich packed by Aunt Helen. Sleepless with excitement the night before, I tossed and turned before finally giving up and rising in the dark to dress. Dawn couldn’t come fast enough.

I admit I was nervous about our first real hunt and hoped my dog wouldn’t humiliate me in front of Uncle Harry, who didn’t have much faith in him. Whistling up Soc, who already waited and whined at the back door, we walked outside into an unexpected world of white ice that sparkled like gems beneath a brassy sunrise climbing above the horizon. Overnight, winter had beaten autumn to the punch and hurled the first snowfall, frosting fields with a frozen crust and turning trees into snow cones. Both of us shivered while Soc, wild with hunt, slipped and skidded across the yard before taking care of his business.

“Here, you’re going to want these. Cold fingers can’t cock a hammer worth a damn,” said Uncle Harry as he handed me a pair of wool gloves and studied the landscape. “You know, this stuff might work in our favor. If nothing else, we should be able to put this knucklehead on some tracks.”

Little did he know that Soc needed no tracks. Winding scent within minutes after entering the field, he creeped to a crouch and locked tight as a drum. Uncle Harry was incredulous.

“I’ll be damned. When did he learn that?”

“Easy, Soc.” I snapped a leash to his collar. “You take this one, Uncle Harry.”

“You sure? Shouldn’t you be the one taking the first shot over your dog?”

Shelterbelt Pheasants by Michael Sieve.

Eck eck eck eck! The bird answered his question before I could. It was a moment I would never forget. Mirroring the season, the gaudy ringneck rose like autumn come to life, iridescence highlighted by a half-risen sun framed in a soft blue sky. I restrained Soc while Uncle Harry, too blinded by the sun to shoot, shaded his eyes as if to salute the departing bird and took measure. Then he pushed the gun like a brush over canvas, fired once, and painted the pheasant out of the air. Feathers drifted lazily in the breeze while Soc raced to retrieve. A broad smile spread over my uncle’s face when I tucked the rooster into his game pouch.

He was a believer now.

The rest of the morning went similarly. Soc brought a bouquet of roosters to gun, Uncle Harry and I nailing a limit apiece. And what Soc lacked in looks, style and control, he made up for in savvy, even if I did have to leash him frequently. It made me proud to watch him sweep across the field like a scythe, side-to-side and back, eyes lit with joy and ears flopping to the rhythm of his run.

Keeping pace as best we could, we watched him work birds invisible to us, tracing threads of scent to slow-sneak points, giddy with tremble and burning with desire. Best of all was the way he sorted scents like a deck of cards, discarding lesser ones for royalty. Circling wide to skip a hen and pin a rooster, it became his signature hunt, this ability to distinguish between genders, kings over queens, that surprised us time and again.

At one point, he held three in a radius of 10 feet until they spooked at my approach and shot off like Roman candles.

“Royal flush!” Uncle Harry yelled.

Too startled to focus, I flock-shot twice and missed everything, getting a ribbing while we waited for Soc to return after a chase.

What didn’t surprise us were the brushes with his four-footed nemeses, skunks mostly, but also porcupines. Since that first early morning disaster, I prepared for emergencies like a Boy Scout. I always carried pliers on my belt for pulling quills and never hunted Soc without soap, peroxide and baking soda stuffed in my vest, the magic potion for quelling skunk odor.

During Soc’s numerous ditch baths, the standing joke was for Uncle Harry to develop a backache on the spot, stiff as a board and unable to bend, he said, and keep his distance.

“Wish I could help,” he’d offer, “but my back . . . you know.”

“Right.”

Wired for Pheasant

With Soc, the bad comprised the good, and I’d be lying if I said he were a good hunter. I didn’t mind, though, paying what seemed a small price for the riches he bestowed on me. Where others saw a lump of coal, I saw an uncut diamond. Ungainly, unorthodox and undisciplined as he was, he forever won my heart during that first hunt marked by gunfire and high fives as we walked a melting, autumn landscape rich with color. I felt like I’d been written into a Robert Ruark story, the first of many sunrises and sunsets bookending memories that I’d cherish for the rest of my life. No poor man ever owned a dog.

Late one afternoon, after Soc had been both skunked and porcupined, I was in no mood for anything other than a shower and supper. That’s when he ignored my command and broke for a runner. I followed, sweaty and gasping for breath, as the three of us ran toward twilight beneath a buttery, Indian-summer moon like lunatics fleeing an asylum.

In the near dusk, I tripped over Soc, whose point was hidden by tall grass bordering a marsh. Sprawling headfirst, I splash-landed almost on top of a rooster flailing to clear the cattails. Before I could yank my gun from the muck, Soc grabbed the pheasant on the rise and pranced proudly around me in triumph.

“You little showoff.”

Drenched in sweat and swamp, I called him out several more times, but he knew me too well. Bringing bird to hand, he pushed and played, licked my face and nearly overturned me until I rose, tucked the rooster into my pouch and hugged him.

“Come on,” I said, leashing him. “Let’s go home before you cause any more trouble.”

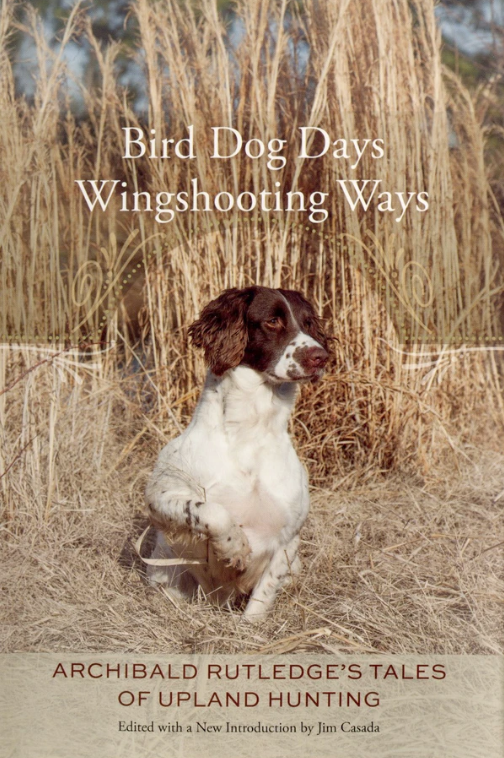

This collection, first published in 1998, turns to Archibald Rutledge’s writings on two subjects near and dear to his heart that he understood with an intimacy growing out of a lifetime of experience—upland bird hunting and hunting dogs. Its contents range from delightful tales of quail and grouse hunts to pieces on special dogs and some of their traits. Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways also includes a long fictional piece, “The Odyssey of Bolio,” which shows that Rutledge’s literary mastery extended beyond simple tales for outdoorsmen. Shop Now

This collection, first published in 1998, turns to Archibald Rutledge’s writings on two subjects near and dear to his heart that he understood with an intimacy growing out of a lifetime of experience—upland bird hunting and hunting dogs. Its contents range from delightful tales of quail and grouse hunts to pieces on special dogs and some of their traits. Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways also includes a long fictional piece, “The Odyssey of Bolio,” which shows that Rutledge’s literary mastery extended beyond simple tales for outdoorsmen. Shop Now