He had worn that old hat from Alaska to Florida. But he could hardly ever bring himself to wear it back to its original home in New Mexico.

Christmas morning. The high country was covered with a foot of new-fallen snow that had come as an unexpected gift during the night. The road that wound up through Sam’s Gap was glazed with a thin layer of silver ice, and we couldn’t get across the mountain from Tennessee and into North Carolina to have dinner with my wife’s family. But thus far here on the western slope, we only had an inch or two of light fluffy powder on the ground.

So, with plenty of leftovers already stuffed away in the fridge and Mary Jane curled up with the cats and her new flannel blanket, I began to sense the seductive tug of the river and the freshly fallen snow and decided to go trout fishing.

I always keep a good fly rod rigged and ready for such errant impulses, and my waders and landing net and old belt pouch are ever on alert. So I stuffed some cold turkey and dressing into a couple of zip bags, along with a big slice of apple-peel pie for dessert, gathered my gear and headed for the river.

I was a mile down Watauga Road before I realized I had forgotten my hat and turned back to retrieve it.

It’s a good hat, old and discolored with the stains of age, given to me long ago by my surrogate brother Frank Simms. And now, many of its stains were my own.

It had been made long ago in Texas from the finest hare-and-beaver felt, and hand-formed by women and men who knew what a fine hat is supposed to be. It was a classic Resistol with a wide, swooping, five-inch brim, and it fit both Frank and me perfectly. It was properly tattered by years of use on horseback, on foot and in pick-up trucks, in snow and rain and high desert heat, with good honest sweat stains and hair stickum circling the base of its crown, and tobacco smudges deeply embedded along its outer rim. Frank had long ago discreetly trimmed it with a simple warm-grey ribbon, and it had spent its first two or three decades with him in Texas and New Mexico and Colorado on it long and steady progression from “new” to “vintage.”

At one time, it had been a very expensive hat. But now it was priceless.

I had worn it for years now myself, in all manner of weather and contemplation, from my home in Tennessee to the tundra and mythic salmon-and-trout rivers of the great north country, to the relentless sand and sun and saltwater flats of the warm southern seas.

But I’d taken it back New Mexico only once.

I had slipped it on in Santa Fe one cold December night during a blizzard as I fetched my rifle and travel bag from the truck when I pulled in to Frank’s big adobe house at the end of a long and grueling three-day run from my home back east. For a moment, Nolene had actually thought I was Frank as she held the front door open for me and helped lift the duffle from my shoulder. I surprised her as I knocked the snow from the old hat’s brim beneath her eve and then set it on her long wooden table. And that’s where it spent the night.

The following morning, Frank and I had headed north at daybreak. But when we got up to the ranch, I left our hat in the truck – for I could somehow never quite bring myself to wear it there where Frank had worn it for the better part of its life.

But now on this soft and silent Christmas morning here in Tennessee, I could wear it trout fishing by myself. I couldn’t help thinking about the day the old hat had come to me. For years I had secretly hoped, without telling anybody, that someday someone there at the ranch might give me a hat, preferably one that had meant something to them – not because I couldn’t afford to buy one myself, mind you, but simply to make it okay for me to wear it there in their presence. For I had seen too many pretenders in New Mexico, most of them transplants from the east or northeast, and especially from southern California, all dressed up the way they thought a real buckaroo should be dressed, wearing cowboy hats that were way too pristine and prissy and over-the-top.

Jeff Wood’s hat would have worked me for my purposes, for Jeff is the real deal. It bore a modest three-and-a-half-inch brim, and had been properly worn and properly abused, as all good hats should be. It was one of the most decrepit pieces of the hatter’s art I’d ever seen and would have been ideal for me. I had all but begged Jeff for it, whenever he might be done with it. Even offered to buy him a brand spankin’ new one to replace it. But Jeff Wood is a proud and stubborn man, with his own mind and ethic. He cares deeply for his friends, as we all do for him, and he just couldn’t bring himself to encumber me with that hat and instead had given it a proper burning.

But Frank understood perfectly and gave me an old hat of his own, one he had long ago retired and abandoned to the upper ledge of his saddle room.

Now what goes on inside one of Frank Simms’ hats is often a strange and mysterious process, and I’m sure that this old hat had been privy to many an odd and unfathomable thought. And now on this cold Christmas morning in Tennessee with the falling snow settling softly on its brim, I wore it as I sat there on the tailgate of the truck, deep in thought myself as I slipped into my waders, then cinched my landing net and belt pack securely around my waist and eased into the river with my fly rod.

The Watuagua was running thick with snow and a tad high, and its roiling surface reflected the muted colors of the chilled pewter sky. I was using my standard rig – a 3-weight with a dry fly tied at the end of a ten-foot leader that I had hand-tapered down to 6X, with a dropper nymph tied be low it on a 14-inch strand of 7X fluorocarbon tippet. I had little hope that anything would take the dry fly on such a cold and delicately balanced morning as this and was using it primarily as a strike indicator. But to my delight, a nice little rainbow sipped it from the surface on my third cast, and I brought the trout to hand and released it.

It wasn’t the only fish I caught that day.

But it was the only fish I really needed.

For the day wasn’t about catching fish. Instead, it was about the fishing. And so I fished.

I fished for trout, I fished for time and I fished for memories. I fished because I needed to fish – to catch up with myself and accept the moment at hand, reveling in that rare and furtive experience when future and past seamlessly intersect and you find yourself living totally in present tense, immersed in the reality of all that is going on around you and within, perfectly in tune with the infinite, all your senses open to the essence of being.

And I caught trout.

I caught a lot of trout.

But as I said, this isn’t a story about catching trout. Instead, it’s a story about Frank’s old hat, so I won’t bother you with the details of how big or how small the trout were, or how many trout I caught. Fact is, I don’t much remember myself – except to say that it was a soft and soulful Christmas day.

The snow continued falling as I fished into the afternoon and then well into evening – not a heavy snow, but a light and silent snow, a snow that brought peace and gratification to my spirit on this, the year’s most peaceful and gratifying day.

And when the snow and the trout and the universe had finished with me and the fishing was complete, I took off that old hat and splashed a hand full of icy water on my face, then sat there alone on the sandbank and had a cold Christmas dinner, warmed by the place and the time and the unseen presence of my surrogate brother back there in Santa Fe and the Lord Himself here at my side.

And though I couldn’t quite recall how I spent last Christmas, and probably won’t remember much about next year’s either, I will never forget the one I spent there alone on the river. Inside Frank Simms’ tattered old hat.

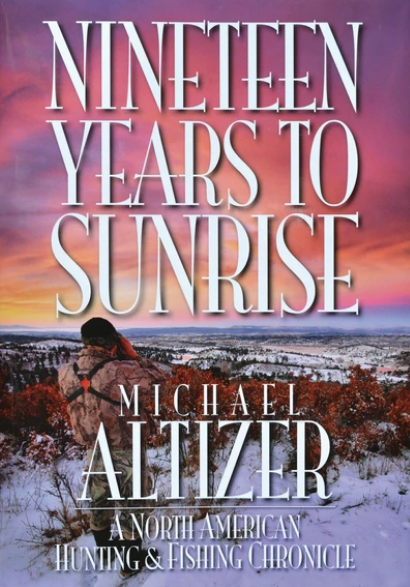

Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now

Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now