I was just a kid when Nikita Khrushchev, leader of the fearsome Soviet Empire, America’s sworn enemy, installed a bristling thicket of Soviet nuclear missiles on his pal Fidel’s island 90 miles south of Florida in October of 1962.

Ater many years and failures, the author landed his first permit.

It looked like Khrushchev really did intend to bury us, as he had promised. Or, more accurately, cremate us in an atomic firestorm.

I was 14 years old. I didn’t want to be buried or cremated anytime soon. Still don’t.

Although our country called Khruschev’s bluff and he moved the warheads back to Russia, Cuba remained a vaguely ominous presence to me for the next half-century. Sort of like living down the road from a guy who sits on his porch cleaning his rifle every time you drive by. So early this year, when my long-time pal, Will Rice, called to ask if I wanted to fish that once-forbidden island, I might have hesitated a little. A lot, actually.

I mean, the Iron Curtain may be folded up and packed in mothballs, but Russia and Cuba are still pretty chummy. And the guy in the big chair in the Kremlin today is clearly at least as crazy as Khrushchev ever was.

Will said, “Listen, about 40 miles off the south coast of Cuba there’s a place called Cayo Largo, an island in the heart of more than 400 square miles of carefully managed bonefish and tarpon preserve. It’s a flats-fishing paradise.”

He let me take the bait, then set the hook: “They’ve caught 500 permit there in the last five years.”

The Avalon fly is deadly on bonefish.

That did it. Five hundred permit. Are you kidding me? Nuclear annihilation? Ha. I laugh at nuclear annihilation. To see numbers like that for permit, I’d march into North Korea and kiss Kim Jong Un on the lips.

Permit! I’ve been trying to get one of those willful, picky, uncooperative things to eat a fly since 1996. I have cast to them in Ascension Bay, up and down the barrier reef off Belize, on Abaco Island, the Cayman Islands, the southern Yucatán Peninsula, and maybe a couple other places I’ve thankfully forgotten. And each time one of them approached the fly I’d offered, it opened its mouth to bite, then suddenly turned away. You’ve heard of a gaggle of geese and a murder of crows? A group of Trachinotus falcatus is called a refusal of permits. Or it should be.

In 2011, after 15 permitless years, I nearly quit flats fishing altogether. How much humiliation can a man take? In the last five years I agreed to a single trip, Christmas Island, and only because there are no permit in that part of the Pacific. So why would I possibly, after all those nerve-wracking failures, agree to go to Cuba and face my finny nemeses once more? Why?

The Avalon fly. That’s why.

I’m one of those guys who believes there exists one magical fly pattern that will not merely catch whatever species of fish I am currently pursuing, but will haul them in like a pollock seiner. Every time I clamp a hook in a vise, I’m convinced I am about to tie such a fly. So the rumor of a whole new and putatively deadly permit pattern obliterated 50 years of Cold War paranoia like a direct hit from a MRBM warhead.

The Avalon fly was designed by Cayo Largo lodge manager Mauro Ginervi and his super flats guide, William Guanche, to imitate the local, pale-colored shrimp that are a major item on the Cuban permits’ menu. As of the day Will and I arrived on Cayo Largo, the fly had landed 566 permit since its inception in 2009. It has also caught innumerable bonefish, snook and even tarpon, not to mention untargeted species: mutton snappers, jacks, barracuda. Basically, anything that eats shrimp is a sucker for this fly.

Still, the question lingered: What if — even armed with a box full of the secret-weapon Avalon flies — the permit of Cuba flummoxed me like they had everywhere else? Where was I supposed to go next?

One of the welcome surprises on Cayo Largo is the accommodations. Avalon Cuban Fishing Adventures puts their anglers up at the Sol Cayo Resort, an all-inclusive extravaganza of a place right out of the Fantasy Island TV show. Hundreds of rooms, a spectacular white-sand beach, four restaurants, numerous fully stocked bars (all drinks included in the price!), swimming pools, tennis courts, even a bocce ball court for your inner Italian. You name it. In short, everything needed for whatever it is people who don’t fish do while on vacation. Personally, I think sitting on the beach at Cayo Largo all day without fishing would be like a night in Vegas spent bowling.

The rooms — which come with fastidious maids — are designed for normal, comfort-seeking civilized people, not obsessed permit fishermen, and served only to show me what knuckle-dragging troglodytes Will and I have been all our fishing lives. In Belize, we stayed in a shack on stilts on a mud-and-mangrove island that was submerged under an inch of water on full moon tides. On Christmas Island, our rooms were cinder-block bunkers. In the Yucatán, lizards prowled the thatched roofs of our palapas and cockroaches tap-danced under the beds. All of which was fine. We were there to fish.

Having lived in Alaska for more than 30 years, most of my local fishing trips mean sleeping bags in wind-wracked tents with huge bears (and mosquitos not much smaller) prowling outside them. Now, in my dotage, I could happily get accustomed to fishing out of immaculate rooms with tiled floors and mini bars full of complimentary Havana Rum and Cristal beers. With age comes wisdom. And decadence.

After checking in, I was out on the balcony changing a fly line on a reel, nervously anticipating our first day of fishing the next morning. Will was in the hotel room spreading camera gear and fishing tackle across his bed.

When a friendly guy from the balcony next to ours called out in vaguely Scandinavian-inflected English, “You are fly fishing?” I admitted I was. He grinned and said, “Then you’ll want to see this.” He fetched his camera and handed it over the railing separating us.

On the digital screen, the man — his name is Eiskert and he is Norwegian — stood on the deck of a flats boat gripping a permit the size of a truck tire.

“Holy cow!” I yelped. “Will, get out here and look at the size of this thing!”

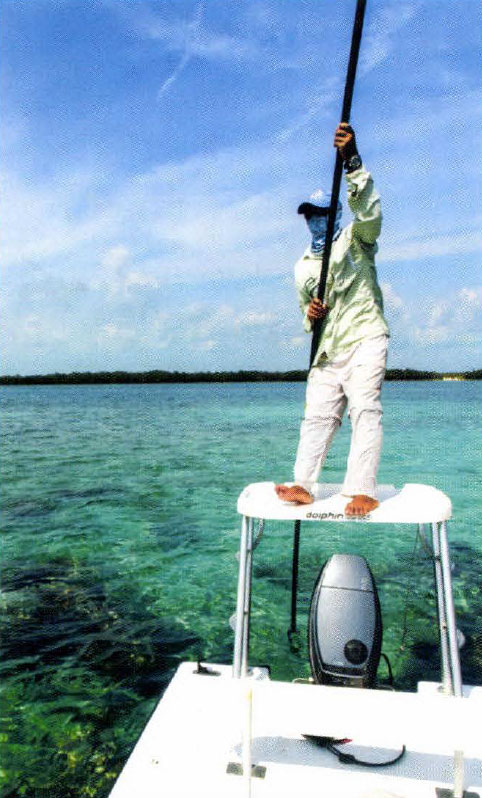

Guide William Guanche poles near the muds where a tarpon takes to the skies.

Eiskert informed us that he had caught it only the day before. Yes, it was permit number 566 caught on the Avalon fly. His guide was the amazing William, who later told us that Eiskert’s permit was, in fact, the largest one he’d ever seen in his 14 years guiding there. They estimated it at 30 pounds.

Eiskert is a very serious angler. Tattooed in blue ink on his left forearm are line drawings of a bonefish, a tarpon, a permit and a snook, and the words Super Grand Slam, Cayo Largo, 2011. He also showed us the tattoo of a shark on his right calf. It said, Greenland Shark, 2001, 1100 Kgs (that’s about 2,300 pounds). It was the second-largest fish of any kind ever taken on sport-fishing tackle. I have a feeling Eiskert fishes like a Norseman on a pillaging run up the coast of old Normandy. I picture him on the casting deck wearing a horned helmet, fly rod in one hand, double-edged broadax in the other.

That first night on the island I had a hard time falling asleep — in spite of several rum drinks and the exhaustion of traveling more than 5,000 miles from Alaska, the trip taking more hours than I care to think about. Thoughts of Eiskert’s fishing triumphs flashed through my brain, but it was not a shark the size of small submarine that haunted me. It was the photo of our strapping Norwegian neighbor straining to hold that 30-pound slab of permit out for the camera.

I flopped around on the bed in the warm Cuban air, the AC doing the best it could but not really geared to cool thick-blooded Alaskans. I was thankful for the ceiling fan, but it was out of balance and emitted a repetitive, two-syllable, guttural sound on each grinding revolution. All night long I heard it saying, “permit, permit, permit, permit, permit …”

My first day of fishing I caught the first tarpon of my life and also my first snook — a species I’d never even seen before.

I hooked the snook up against a log-strewn bank and managed to keep it out of the sticks long enough to get it to the boat. The tarpon showed up while poling the same shoreline, and ate the same fly the snook fell for—a black-and-purple Tarpon Toad. We also sight-fished to tailing bones in ankle-deep water in a mangrove maze, similarly struggling, with mixed success, to keep hooked fish out of the barnacle-studded roots.

It was a great day, sunny and nearly windless, and having landed a bonefish, a tarpon, and a snook, we joked that I’d caught a quasi-grand slam. Of, course, the permit is the fish that makes or breaks a true slam, and I’d blown every cast to them that day. No surprise there. I’d been doing that for two decades. But the week had just begun.

Having caught two new species, I slept soundly that night, though through my dreams I heard that ceiling fan muttering its mantra. If I had landed a marlin, a tuna, and a white whale that day, I’d still have wanted a permit. Compared to me, Melville’s Ahab was a poster child for mental health.

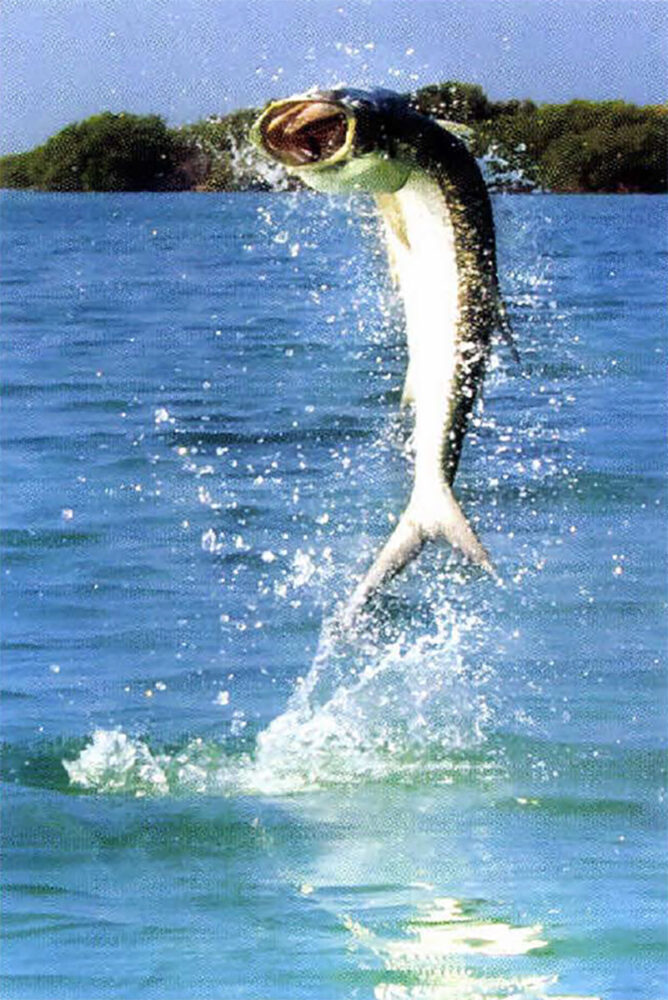

Taking flight.

On the second morning, the light and the wind weren’t right for the open-ocean permit flats, so we spent some time fishing a channel for rolling tarpon and Will caught a nice one that jumped all over the sky before coming in. But after lunch it was time to go out to the muds.

Racing across mile upon mile of water as clear as white rum, we began to see nearly opaque ovals of cloudy blue-gray soup on the surface. They looked like nothing more than cloud shadows at first. But as we approached one, William cut the engine and we rocked to a halt, and I could see that we were near the edge of maybe five acres of muddied water.

It was my turn on deck. William climbed the poling platform and poled the boat to within a hundred yards of an enormous mud cloud created by stingrays and hundreds, maybe thousands, of bonefish rooting in the soft bottom for clams and sea worms. The mud they stirred drifted downwind, carried by tide and ocean currents. The whole area swirled with uncountable bonefish, snappers, jacks, needlefish, boxfish, and every other imaginable kind of inshore species congregating to feed on the shrimp and baitfish dislodged by the bottom feeders. Sharks and barracuda moved in to prey on anything smaller than themselves. The result was a maelstrom of feeding fish. And, most importantly, it included permit. Lots of them.

If you cast just about any fly into the mud cloud itself, you will almost certainly hook something — usually a bonefish, because they are probably the most numerous species in the frenzied feeding zone, and among the fastest and first to get to the fly. But blind-casting is like blind dating. I mean yes, you’ll catch lots of fish but that’s about as enjoyable as having dinner with a strange woman who wants to talk about her food allergies.

William moved us along the perimeter of the huge mud, keeping the boat far enough away to see fish darting out into the clear water in pursuit of escaping bait. Within minutes, he said, “Permit. Eleven o’clock, thirty meters. Wait!” He jammed the pole into the bottom to turn the boat, and I peered into the sunny glare, not seeing anything but water.

“Where?” I said. “I can’t see them.” And then I could.

Maybe 50 feet off the port beam, there was a small “refusal” of permit unmistakably flashing gold highlights off their sickle fins and scissor-like tails as they zig-zagged through some kind of panicked bait.

“Cast,” William said, “Twenty meters.”

Most automobiles in Cuba predate 1960, which is when the US began a series of embargos that are still in effect.

For once, the gods of permit fishing smiled. The fly landed just short of the fish. I stripped two, maybe three times, and saw the permit — now five or six of them, at least — turn and race after the fly. I kept stripping, the fish following behind it toward the boat. Miraculously, the fly was not ambushed by a snapper, a jack, or even a pesky bonefish. (On Cayo Largo the bonefish are so big and fat they make Christmas Island and Ascension Bay bones look like lawn darts. Yet they are also so plentiful that five-pounders stealing your fly out from under the noses of permit actually seem like a nuisance).

Two strips more, and the fastest or hungriest of the permit pounced. The line went tight and started flying off the screaming reel. My two-decade slump ended 15 minutes later when Will took a photo of Cayo Largo permit number 567 caught on the Avalon fly.

I figure I’ll stop grinning in another month or so.

It was 2:30 in the afternoon. What was I supposed to do with the rest of the day? With the rest of my life? Besting your nemesis has its downside.

“Still enough time for a grand slam,” William said. “Let’s go find some tarpon.” He started the Yamaha four-stroke.

A grand slam. Another reason to live. Thank God.

One of the other perks of fishing Cayo Largo is the fabulous possibility of a grand slam — which is not too hard, once you’ve caught a permit. Of course, that’s like saying, it’s easy being wealthy: all you have to do is have lots of money. But, seriously, look at the statistics: Last year (2014) Cayo Largo had 64 grand slams and 22 super grand slams (permit, bonefish, tarpon, and snook).

The Avalon fly, the boundless flats, and the finely honed guiding services there give anglers more promising shots at permit than anywhere else on earth. Bonefish are prolific. And though giant tarpon are mostly available only in late spring and early summer, the resident, year-round five- to twenty-pound toddlers ensure the probability of a grand slam — again, once you’ve caught a permit.

A Cold War beauty enjoys Cuba’s most-famous export.

With two hours of fishing time left on the clock, William roared inland from the ocean flats and plowed to a stop in a mangrove-jungle lagoon. Slowly poling along the edges of the trees, he soon spotted tarpon lurking under overhanging branches. Nothing to it, right? This was going to be easy.

Not.

Two hours later and more botched casts than I care to enumerate, I was still thrashing the water. I put the big 2/0 fly into the trees again and again. I slammed it on top of the fish and spooked them. I wrapped the line around the tip of the rod. I hit myself in the back of the head. I demonstrated nearly every example of bad casting that afternoon, trying to complete the grand slam.

William’s patience ran thin. I could hear exasperation in his voice. But he still continued to encourage me. “Just cast it straight in there between those two trees and under that log. See them in there? You can do it.”

Yes, I saw the fish parked behind a log under a wall of towering mangroves. But actually I could not do it. I could cast it across the log and get snagged. I could launch it into the mangrove branches above. That I could do. And I did.

William smiled as he poled us in close enough to extract the fly from the foliage. “It’s ok. We’ll keep looking.”

I cast into more trees. I cast into thick mats of surface weeds. I cast into everything but the groups of tarpon loitering under the overhanging trees like commuters waiting for a bus.

A tattoo fit for a serious flats angler.

Then, at five o’clock, the day running out, William’s patience running out, my right arm running out, I finally caught a tarpon. It weighed maybe six pounds and jumped higher than my head before coming to the boat.

As William — really smiling now — stowed the pole and got ready to start the engine for the run back to the lodge, I said, “William, I’ve decided that I am not going to give you a tip this week.”

William, always open for comedy, said, “Oh really? No tip?”

“No,” I said. “Instead, I’m calling Pope Francis and asking him to make you a saint.”

William smiled slyly. “Oh, that’s too much. A small tip would be enough. Really.”

Will and I cracked up. We still had four more days of fishing with this smart and funny guide in one of the fishiest and most beautiful places we’d ever been.

Get a hold.

Spirits were high back at the lodge that night. Rum drinks flowed. We celebrated my first permit, first tarpon, first snook, my grand slam. We celebrated the great guides, the fabulous Cuban sunshine, and the endless fish-filled flats of Cayo Largo. Oh, yeah, and the end of old Cold War enmities between our two countries.

A friendly Cuban permit had extended a warm welcome to his former enemy, an American. One week later President Obama met with Raoul Castro, laughing and shaking hands like old pals.

Coincidence? I don’t think so.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the September/October 2015 issue of Sporting Classics.

Leander McCormick literally fished his way around the world. These many miles produced a catalog of stories in his book. From his first perch on the shores of Lake Michigan, to youthful pursuits of eels in England, to ultimate angling for the giants of the sea, he demonstrates a deep insight into both the fish and the people who pursue them. Having angled for and caught dozens of different species of fish, McCormick dryly comments, “Some were more sport to catch than others, but I assert that all fishing is good, though some is better.” Buy Now

Leander McCormick literally fished his way around the world. These many miles produced a catalog of stories in his book. From his first perch on the shores of Lake Michigan, to youthful pursuits of eels in England, to ultimate angling for the giants of the sea, he demonstrates a deep insight into both the fish and the people who pursue them. Having angled for and caught dozens of different species of fish, McCormick dryly comments, “Some were more sport to catch than others, but I assert that all fishing is good, though some is better.” Buy Now