But aside from latent starlight and the occasional ghostly white egret feather that lay among the pine needles and leaves and withered fronds at my feet, I was surrounded by total darkness and any attempt at vision was futile.

Flashlights were worse than useless, for not only could they severely impair any night vision we might have had, they would alert the big boar to our location.

Blackroot and palmetto, gallberry and bluestem clutched at my legs and arms as I carefully eased alone, step by silent step through the thick underbrush, scanning the night with my hearing and sifting the sinuous breezes with my nostrils for any hint of blood or mud or musk that might offer the slightest evidence of the big Florida boar I had wounded at dusk, and the impending charge I felt certain was coming.

None of us were sure how seriously he was hit. Junior had long since dissolved into the night off to my left and Senior around to the right as we pressed forward toward the deep-flowing slough somewhere out in front of us.

I could hear Yellow and Abe, our good Partin curs, coursing the understory in search of the old boar.

Senior had told me, “If they catch him, they won’t let go, and we’ll likely have to finish him off with our knives. Rifles are pointless in this sort of cover at night, but you might be able to put one in his ear with your pistol.”

And so with Orion’s belt our only point of navigation, we’d entered the swamp together. But I was completely alone when I heard the sudden rustle of cutting hooves and clacking tusks and dried palmetto fronds seven yards below me as I topped a little hummock and brought my pistol to bear.

It was a relatively new pistol,a Ruger single-action revolver in 45 Colt, with custom fitted elk-antler grips. I had never actually used it on any sort of game—especially anything that could do me harm. But that was what the gun had been built for, and I had practiced diligently with it for months leading up to this hunt, primarily at short range with quick, instinctive shots, in anticipation of just this sort of situation.

And now I was glad I had—for never had a gun felt so reassuring in my hand.

That’s how a gun becomes your own, you know.

At first it may be only a tool. It might eventually become a friend or, at its best, a trusted companion, a comfort in dark places and dark times, a carrier of memories you will either cherish or long to forget. Then again, perhaps it will be none of those things and you’ll eventually pass it along to someone else.

Such has been the fate of most of the guns I’ve ever owned. But the ones that are left are the ones I know and trust.

Among them are two 12-gauge veterans from the past century, each a gift from a friend. One is an ancient L.C. Smith side-by-side from Burl Scott in Kentucky, and the other is a Winchester Model 98 pump entrusted to me years ago by a dear friend and guide who has hunted across the globe. Both guns found immediate use and quickly earned my trust.

Then there’s the custom-stocked Ruger Number 1 falling block rifle in 300 Winchester Magnum. By the time I bought it from my old co-conspirator Bob Matthews years ago, he had already taken more deer and elk with it than he could remember. Bob hadn’t used the rifle in more than a decade, and we had trouble coming up with a load it liked. But when we tried 70 grains of Hodgdon H4831 powder behind a 200-grain Nosler Partition bullet, the old gun came to life, placing three shots well inside an inch at 100 yards. Since then, I have taken everything from coyotes to mule deer to elk with it and have never needed a second shot.

The most recent, and possibly the last, addition to the guns I depend on is a luscious little custom-built 280 Remington. My pal Jim initially came up with the classic Model 98 Belgian FN Mauser action around which the rifle was built. Cory Truitt provided a stock blank that is just about the prissiest piece of walnut I’ve ever laid eyes on, and Guthrie Taylor fitted a 24-inch Shilen barrel and three-position safety to the action. Master stockmaker Monte Fleenor found some exquisite Dumoulin bottom metal for the action, and by the time he had worked his wizardry with the walnut, we had a rifle for the ages. And now, less than three months after it was completed, the little beauty has already accounted for a pair of whitetails.

But the two old friends that are as much a part of me as my arms and legs and one good eye are the guns that came to me from my Dad. One is a Marlin 336A that he bought for himself the day he came home from Pearl Harbor, and the other is a little 20-gauge Beretta single-shot he gave me when I had just turned seven. The old Beretta was part of a multi-gun trade that Dad engineered back in the summer of ’57. I killed my first game with it a couple of months later on opening day of squirrel season, and I last used it just a few weeks ago on doves.

But it’s the old Marlin that occupies the dearest place in my heart.

Dad had been at Pearl Harbor when it was hit on that infamous Sunday morning in 1941, and when the Korean War broke out nine years later, he was called back to the Navy and returned to Pearl Harbor. I was six weeks old when he left.

While there, he read about this particular gun—a longer-barrel, short-magazine version of Marlin’s classic 336, chambered in 35 Remington. I was 14 months old the day he finally returned, and Mom and I met him at the train station in Bluefield. On our way home to Bishop, he stopped at Ward’s Hardware in Tazewell to pick up some supplies, and, lo-and-behold, they had two of the new Marlins he’d read about.

One of them came home with us.

To me, that rifle was always magic. Dad took numerous deer with it during his lifetime, and I first hunted with the gun on my own in my early teens. I killed a big black bear with it in northwest Ontario a few months before Dad died, and he told everyone except me that if anything ever happened to him, the old gun was to be mine.

It has since carried me from Canada to New Mexico to Michigan and the swamps of northern Florida for everything from deer and elk to wild hogs and coyotes. I assure you, the old gun will never be sold, though someday it will be given to the little man who is next in line to cherish it.

That’s the way it is with such guns. They’re not ours simply to own, but to treasure and make certain that when it’s time to pass them along, their care and honor are secured.

And as for that Ruger revolver with the elk-antler grips and the big wounded boar?

I would love to tell you he came barreling straight at me through the darkness and that I dropped him with one quick, clean, perfectly placed shot to the base of the skull. But the pure truth is that instead of charging me, he bolted away into the night.

Junior, Senior and I all heard him clearly as he hit the slough and splashed across, before tearing away into the thick undergrowth on the far side until we could hear him no more.

The safe and sensible part of me was relieved. But the part I live for was surprisingly disappointed as I stood there alone, pistol drawn.

The big boar was gone.

But that old revolver is still mine.

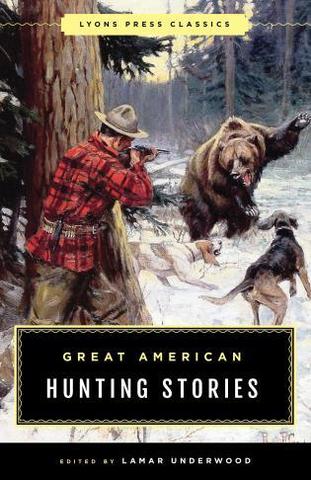

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Shop Now

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Shop Now