An excerpt from Roosevelt’s Good Hunting: In Pursuit of Big Game in the West, published in 1907.

In the fall of 1896 I spent a fortnight on the range with the ranch wagon. I was using for the first time one of the then-new small-caliber, smokeless-powder rifles, a .30-30 Winchester. I had a half-jacketed bullet—the butt being cased in hard metal, while the nose was of pure lead.

While traveling to and fro across the range, we usually broke camp each day, not putting up the tent at all during the trip. But at one spot we spent three nights. It was in a creek bottom, bounded on either side by rows of grassy hills, beyond which stretched the rolling prairie. The creek bed, which at this season was of course dry in most places, wound in S-shaped curves, with here and there a pool and here and there a fringe of stunted, wind-beaten timber. We were camped near a little grove of ash, box-alder, and willow, which gave us shade at noonday, and there were two or three pools of good water in the creek bed—one so deep that I made it my swimming-bath.

The first day that I was able to make a hunt I rode out with my foreman, Sylvane Ferris. I was mounted on Muley. Twelve years before, when Muley was my favorite cutting pony on the roundup, he never seemed to tire or to lose his dash, but Muley was now 16 years old, and on ordinary occasions he liked to go as soberly as possible; yet the good old pony still had the fire latent in his blood, and at the sight of game—or, indeed, of cattle or horses—he seemed to regain for the time being all the headlong courage of his vigorous and supple youth.

On the morning in question it was two or three hours before Sylvane and I saw any game. Our two ponies went steadily forward at a single foot, or “shack,” as the cow-punchers term what Easterners call “a fox trot.” Most of the time we were passing over immense grassy flats, where the mats of short, curled blades lay brown and parched under the bright sunlight. Occasionally we came to ranges of low, barren hills, which sent off gently rounding spurs into the plain.

It was on one of these ranges that we first saw our game. As we were traveling along the divide, we spied eight antelope far ahead of us. They saw us as soon as we saw them, and the chance of getting to them seemed small. But it was worth an effort, for by humoring them when they start to run, and galloping towards them at an oblique angle to their line of flight, there is always some little chance of getting a shot.

Sylvane was on a light buckskin horse, and I left him on the ridge crest to occupy their time while I cantered off to one side.

The pronghorns became uneasy as I galloped off, and ran off the ridge crest in a line nearly parallel to mine. They did not go very fast, and I held Muley in, who was all on fire at the sight of the game. After crossing two or three spurs, the antelope going at half-speed, they found I had come closer to them, and, turning, they ran up one of the valleys between two spurs.

Now was my chance, and, wheeling at right angles to my former course, I galloped Muley as hard as I knew how up the valley nearest and parallel to where the antelope had gone. The good old fellow ran like a quarter horse, and when we were almost at the main ridge crest I leaped off and ran ahead with my rifle at the ready, crouching down as I came to the skyline.

Usually on such occasions I find that the antelope have gone on, and merely catch a glimpse of them half a mile distant, but on this occasion everything went right. The band had just reached the ridge crest about 220 yards from me across the head of the valley, and I halted for a moment to look around. They were starting as I raised my rifle, but the trajectory is very flat with these small-bore smokeless-powder weapons, and taking a coarse front sight I fired at a young buck which stood broadside to me. There was no smoke, and as the band raced away I saw him sink backward, the ball having broken his hip.

We packed him bodily behind Sylvane on the buckskin and continued our ride as there was no fresh meat in camp, and we wished to bring in a couple of bucks if possible. For two or three hours we saw nothing. The unshod feet of the horses made hardly any noise on the stretches of sun-cured grass, but now and then we passed through patches of thin weeds, their dry stalks rattling curiously, making a sound like that of a rattlesnake. At last, coming over a gentle rise of ground, we spied two more antelopes half a mile ahead of us and to our right.

Again there seemed small chance of bagging our quarry, but again fortune favored us. I at once cantered Muley ahead, not towards them, so as to pass them well on one side. After some hesitation they started, not straightaway, but at an angle to my own course. For some moments I kept at a hand-gallop, until they got thoroughly settled in their line of flight; then I touched Muley, and he went as hard as he knew how.

Immediately the two panic-stricken and foolish beasts seemed to feel that I was cutting off their line of retreat, and raced forward at mad speed. They went much faster than I did, but I had the shorter course, and when they crossed me they were not 50 yards ahead—by which time I had come nearly a mile.

Muley stopped short, like the trained cowpony he was. I leaped off and held well ahead of the rearmost and largest buck. At the crack of the little rifle down he went with his neck broken. In a minute or two he was packed behind me on Muley, and we bent our steps towards camp.

During the remainder of my trip we were never out of fresh meat, for I shot three other bucks—one after a smart chase on horseback, and the other two after careful stalks.

The game being both scarce and shy, I had to exercise much care, and after sighting a band I would sometimes have to wait and crawl round for two or three hours before they would get into a position where I had any chance of approaching. Even then they were more apt to see me and go off than I was to get near them.

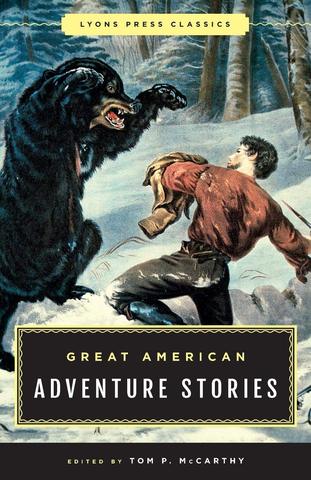

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now