Whether a croc or leopard, the brave young woman handled each close encounter with the same degree of calmness.

Mary left the dugout canoe and started to walk through a forest. The rain was coming down hard, but it was warm rain, not the cold rain of her native England. Then came a ferocious wind that shrieked and roared as it raced through the dense forest, bending the mighty trees in its wake; she had undoubtedly encountered a tornado.

As she made her way through the mayhem, Mary heard terrible creaking and snapping sounds high up in the canopy as the storm tore through the upper branches. The intense wind turned many vines into whips that lashed the tree trunks with loud cracks that echoed through the forest. Fearing for her life, Mary crouched close to the forest floor to avoid the debris crashing all around her. In the distance, she caught sight of a rocky embankment that might provide sufficient shelter, but to get there, she first had to cross a small creek. As she began wading into the swirling stream, Mary’s petticoats and ankle-length woolen dress were quickly soaked through, making her going heavy and uncomfortable.

Once across the creek, she struggled up the embankment, then stopped briefly to catch her breath beneath an overhanging boulder. After several minutes, the determined young lady resumed her arduous climb and eventually reached the crest of the hill. Looking over the top, she was horrified to find herself face-to-face with a huge leopard, which had also sought shelter there from the storm. The big cat was crouched under a dense pocket of foliage only three feet away.

Armed only with a knife she kept sheathed at her waist, Mary knew only too well that it was inadequate protection against a deadly predator.

The adventurous young lady was Mary Kingsley, a beautiful, 32-year-old, English-born writer and explorer who was traveling alone through West Africa and the French Congo in 1894. Two years earlier, after her parents died within three months of each other, Mary decided to use her inheritance to finance a trip to West Africa to study religious fetishes of its native peoples. That was in 1893, a time when it was unthinkable for a young lady to attempt such a dangerous endeavor, much less do it alone.

Her mode of transport, a cargo ship, was also considered unconventional for a single woman traveling by herself. It took her several months to sail from England to West Africa, then along the coast from Freetown, Sierra Leone, to Luanda, Angola, and finally to travel inland from Guinea to what is now Nigeria, collecting scientific specimens for the British Museum along the way.

Following that adventure, Mary briefly returned to England before setting sail once again for the West Coast of Africa, this time via the Canary Islands. On her trip in 1894, she hoped to explore many places never before visited by a European, let alone a young white Victorian lady traveling alone.

It was on this expedition that she taught herself to row a dugout canoe singlehandedly through some of the most treacherous waters in the world. She traveled the remote regions of Gabon and the French Congo, meeting with many tribes along the way. Some, like the Fang, practiced cannibalism and had a reputation for being most unfriendly.

Undaunted, the daring young lady seemed to fear nothing and possessed the true spirit of all explorers going into the unknown. Mary respected the wild animals she encountered and considered it unladylike to carry a gun. She believed that when faced with danger, a simple unthreatening retreat was the best form of defense. Her theory was certainly put to the test when she encountered the leopard.

Mary did not take her eyes off the cat as she began to back away. To escape the strong winds, the leopard was hunkered down next to some large rocks where, for some reason, it seemed unable to see or smell her. Lashing its tail from side to side, the cat was angered by the storm but not by her presence.

Mary moved a short distance back down the embankment, where she found an ideal spot to avoid both the storm and the leopard. The young lady was shaking as she crouched under some rocks, hoping the rain would discourage the leopard from looking for her.

Mary moved a short distance back down the embankment, where she found an ideal spot to avoid both the storm and the leopard. The young lady was shaking as she crouched under some rocks, hoping the rain would discourage the leopard from looking for her.

She knew that leopards were not known for their scenting skills, and while she could still hear it growling and slapping the ground with its tail, she assumed she would be safe if she just stayed put. It seemed like hours that she had been there, shivering under the rocks, but in reality, it was only about 20 minutes.

As Mary began to ponder her next move, she suddenly realized the leopard had become silent. This filled her with terror, as she no idea where it had gone.

By then the rain had eased off, so the brave young lady decided to slip back up the embankment and take a peek over the top. To her relief, the predator was no longer in sight, though she continued to wonder where it could be…was it stalking her?

After some time, Mary decided to take advantage of the lull in the weather and risk heading back to her dugout. Knowing this might only be a brief reprieve from the storm, she moved as fast as possible over the fallen tree limbs, keeping her eyes peeled for the leopard.

Mary breathed a huge sigh of relief when she finally got back to her dugout. This would not be her only encounter with leopards and other dangerous wildlife during her expedition. In each case she demonstrated the same degree of calmness.

One day, while quietly paddling down a river, a huge crocodile slid into the back end of Mary’s dugout canoe. She only became aware of the monster when she realized the canoe was carrying more weight and her paddling had become much harder.

Mary turned to see the beast crawling toward her. She quickly pulled her paddle out of the water and smacked the croc on the nose several times. The beast reacted by rolling out of the dugout and disappearing in the murky water. Mary calmly returned to her paddling as if nothing had happened.

On another occasion, while staying with some missionaries, she was awakened in the middle of the night by loud growls and snarling outside her hut. Most people, especially if unarmed, would not venture out to see what was happening. But not Mary; she wasted no time going to investigate.

As she stepped from the mud hut in the hazy moonlight, she was confronted by a whirling mass of bodies savagely fighting each other. Even though it was hard for Mary to identify the culprits in the dim light, she picked up a couple three-legged stools and threw them as hard as possible at the animals in the hope of breaking up the fray.

When the animals separated, she could see it was a leopard and a local dog. As the mongrel limped away whimpering, the leopard turned toward Mary and crouched, ready to pounce.

She grabbed a heavy, earthenware jar and, using all her strength, hurled it at the leopard. It was an accurate throw, the jar bursting like a bombshell against the cat’s head and sending it racing back into the bush.

Mary Kingsley went on to have many adventures before returning to England in 1895, when she wrote Travels in West Africa, which was published in 1897. Then, during the Boer War in 1899, she set sail for South Africa, where she worked as a journalist before contracting and dying of typhoid fever in 1900. She was only 38 years old.

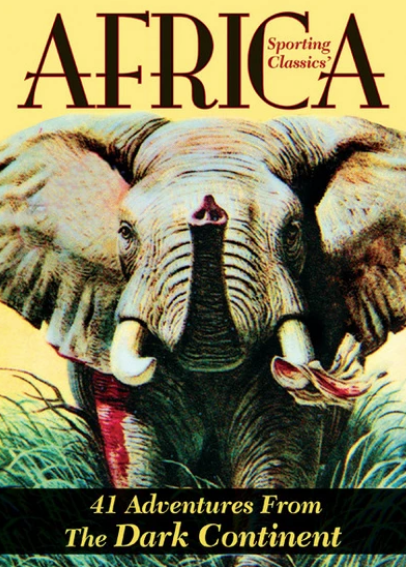

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt, Markham – the legends in outdoor literature are all here, sharing their stories of deadly encounters with dangerous game, of bizarre run-ins with witch doctors, gorillas and man-eaters, of safaris into the uncharted wilds of deepest Africa.

Illustrated by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now