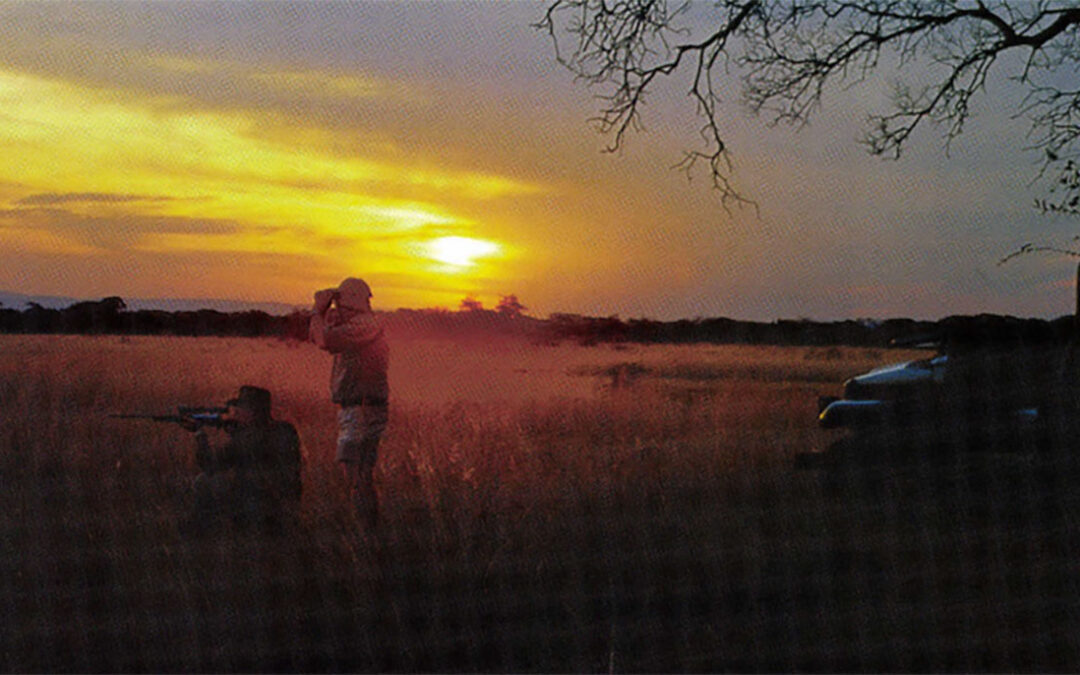

It is at the edge of dark, that pandemonium erupts.

One day, I want to shoot a buffalo. With paces between us, facing his dare. I want to know for once before I die, even if on the day I die, the tremble of doubt and the taste of fear. It is only just, before all I have hunted. Perhaps, also, a chui, a lovely, spotted tom of maybe seven feet. No longer, I think, elephant or lion or rhino.

But before them all has persisted a lifelong yearning for the ghostliest of the antelope. For surely as the Fabled Five portray the ferocity of Africa, the kudu perfects its grace.

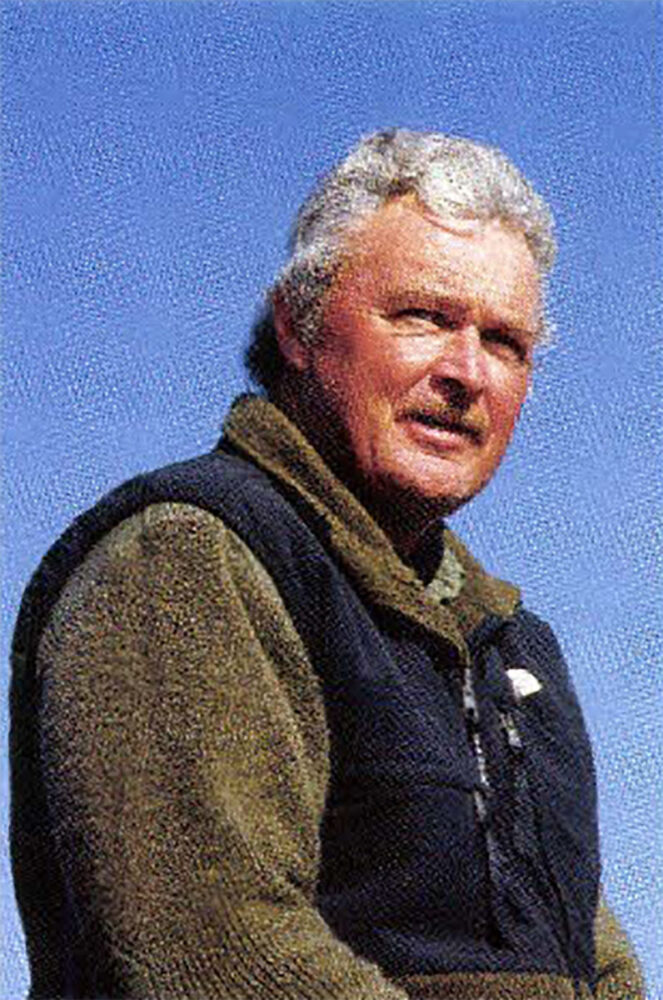

PH Garry Kelly

“You must be ready,” Garry Kelly said to me Britishly on the foresight of our safari, before the flickering spitfire of the boma, over a dinner of Ayala filet, cinnamon butternut and a toast of Hamilton Russell pinot. “Where we will hunt it must be thick, for on the edge of it is where the biggest bulls will be.

“Should I say ‘Shoot!,’ you must do it quickly. They will not wait.”

So opened an odyssey, a journey that had bridged 9,000 miles, 59 years and the arc of a dream, to spend itself in the most spellbinding six days of my life. And I could not believe, believe that I was finally here, except for the evening sky. Vast and dark, much as Montana or Dakota, but deeper — so deep you could look beyond a million stars and find the enchantment that could only be Africa. Until I lay in the shallow hours of the morning, wondering at the impala rams, randy and roaring with rut. Until I listened to the rhythmic, fluid words of a black man, and they were Zulu.

It is chilly this first morning. The sun struggles to chin the gray-blue humps of the Drakenberg foothills. It is May, the African autumn.

Behind the south wind, a cold front will swell.

“Opposite you chaps,” Garry observes.

You must think in opposites here. Not right, but left. Not of the North Star, but the Southern Cross. English, yes, but Afrikaans, the brogue of the Isles, Zulu, isiXhosa, the Bantu songs of the natives, as well. You must catch the sway of the land.

Close around is the bush, an ever-more mix of acacia and grassland. Eleven species of acacia stipple the panicum grasses, from our four-foot scrub to robust trees. And halfway between, the canopy of the silverleafs, the bellies of their foliage, the inspiration for their name, creating at a distance the illusion of a blossoming. Sometimes the collaboration is hardly more than a scree, through which you can really spy the for and shadow of game. Again, it’s so thick and thorny as to be hardly penetrable, dark and deep, where the buffalo will wait to return your pain. Occasionally, towering haughtily above its homebred neighbors, grows a eucalyptus tree, a pine, a blue gum, that immigrated west with an Aussie settler.

Close around is the bush, an ever-more mix of acacia and grassland. Eleven species of acacia stipple the panicum grasses, from our four-foot scrub to robust trees. And halfway between, the canopy of the silverleafs, the bellies of their foliage, the inspiration for their name, creating at a distance the illusion of a blossoming. Sometimes the collaboration is hardly more than a scree, through which you can really spy the for and shadow of game. Again, it’s so thick and thorny as to be hardly penetrable, dark and deep, where the buffalo will wait to return your pain. Occasionally, towering haughtily above its homebred neighbors, grows a eucalyptus tree, a pine, a blue gum, that immigrated west with an Aussie settler.

We cruise slowly, searching. An ostrich darts into the path, effortlessly outstrides the Cruiser. Francolin clatter airborne. Zebra whirl and run. A gather of warthogs scatters, high-tailing it for cover. The Cruiser wallows abruptly in and out of one of their rooted-out-holes, as unpredictably the neck of a giraffe ladder sits way into the tallest trees. At every turn there is adventure.

The bush opens to a grassy veld – the scene as beautiful as the word, against the purple backdrop of the mountains — as an oryx skittishly retreats. Near its center, wildebeest race senseless circles in the lemon light of the waking sun.

Again, the bush swallows us, and suddenly, not 60 yards off our trail, is my first kudu bull. He looms the color of the wispy smoke that rises from a damp fire. Stock-still he stands, half-hidden, and I find him by the flare of his great bellows-like ears. Afterward emerge the tall, thin legs, the white pickets of his flanks, the victory mark of his forehead, the twirl and gather of his horns. He is utterly erect and regal, and I have forgotten I am there to shoot.

“Young,” Garry decides fortunately. Mid-40’s, not the 50-inch plus majesty we have set our hat for. The bull nervously evaporates. “He’ll be a good one in a couple of years — has that very deep spiral.”

He smiles, knows I was shaken. Again. The afternoon before, barely after we arrived, there had been a good warthog. I had the rifle on him, longer than I should, and he had escaped into the grass.

“It’s nothing,” he had told me quietly, “you must shoot only when you’re comfortable. I know the passion.” My respect for him had soared.

Enoch, our Zulu tracker, has stopped the truck and Garry beckons me off. Ahead, through the shadowy bush, is the sunlit sprawl of a vast open plain. Enoch leads the stalk, Garry, myself and Todd Roberts, our camera man, behind, Single-file — dodging the crack of a stick, the telling scrape of the thorns. Several hundred yards later we pause, squatting in a huddle and glassing a trio of blesbok, while Enoch and Kelly whisper together in native tongue their measure.

Enoch, our Zulu tracker, has stopped the truck and Garry beckons me off. Ahead, through the shadowy bush, is the sunlit sprawl of a vast open plain. Enoch leads the stalk, Garry, myself and Todd Roberts, our camera man, behind, Single-file — dodging the crack of a stick, the telling scrape of the thorns. Several hundred yards later we pause, squatting in a huddle and glassing a trio of blesbok, while Enoch and Kelly whisper together in native tongue their measure.

Garry motions me up.

“The one in the middle,” he instructs, and in a rush I am facing the first shot of Africa. It’s the sheer spell of the place I suppose. I’ve hunted as long as I’ve lived and I’m shaky as a pre-election promise. The buck faces us. I can see the bles, his white blaze, brilliantly through the scope. “Wait,” Garry says softly, “wait until he turns.”

I’m trying to talk myself down, and for the first time in my life I can’t. Garry has to know. Still, he whispers “Now, take him!” for the buck has turned broadside and his hide burns mahogany-red in the sun, like the heart of the tree, against the tawny yellow sprawl of the veld and the blue of the mountains. I’m still fighting the rifle when it goes off. Knees buckle on both ends, as the buck drops in a whumph.

Minutes later, I kneel, to touch my first African animal. At the skinning shed, Enoch cuts out the blesbok’s paunch, empties its sour green contents on the ground and slices from the stomach wall a sliver, which he divides equally between the two of us. For among the Zulu, there is a ritual of safari, a tradition of time, earth and eternity. The Proposition of your first kill, that by eating this portion of the animal you do it honor, become forever a part of it and what it has consumed, and thereby a part of the earth itself.

“Well done,” Garry offers. Not so well, the shooting. I must do better.

In the afternoon, as the shadows spend their secrets on the backsides of the hills, an opportunity at a tremendous impala ram runs barren. Fate hands us another. A good gemsbok stands grandly under an acacia tree, distantly across the veld. Too open, the terrain, for a stalk. We back away, to the Crusier.

“When I say jump, jump,” my PH urges. “Jump!” I cradle the rifle as we pile out, slump flat into the dust as Enoch pulls on with the truck. Crawling on our elbows, we close. The apprehension is electric, even at a couple hundred yards, but the gemsbok is not yet disturbed.

“Tight, against me,” Garry hisses, jamming up the sticks.

“Take him.” We sit Indian-legged, and I’m trembling again as I hastily frame the target, forcing my attention away from the spectacular saber horns, which jut head to haunch.

We walk to him in the glow of sunset — even as far across the red-orange plain there are graphite sketches of scattered, feeding animals — and my spirit is as mellow as the light. I’m warm with the hunt, lost once more with how, finally, this can be. But there waits the gemsbok, big and chalk-gray as dirt, maned jet-black, the stunning throw of its horns better than a yard and in the ceremonial markings of its face the imagery of Africa.

The hunters were in their Land-Cruiser when they encountered this puff adder — not the case for untold numbers of Africans who stumble upon the dreaded snakes.

At the lodge, Rob Fancher and Steve Scott are flush with their own hunt. Rob fronts the U.S. operations of Swarovski, the renowned Austrian optics builder, and Steve, who heads WEI Productions, produces the Safari Hunter’s Journal, a popular spot for The Outdoor Channel. Todd and Steve, along with pastels artist Natalie Caproni, are here to film a show. Both Rob and Steve are accomplished, world-traveled sportsmen. While we’re here, Steve will celebrate his 100th night in Africa, and Rob will spin a hundred tales.

Garry Kelly and Bonwa Phala Safaris are a story to themselves.

In 1820, amid the tribal unrest of Mfecane, a daring young Irishman named William Edward O’Kelly forged his way into the African bush, the first man to settle Swaziland. Behind him came sons and grandsons, inheriting his love of the land and the wilds. Among them, perhaps Garreth Cullen Kelly embraced it fondest, especially the passion for hunting. It would become the grail of his life, after his father sent him to work with Norman Dean, of Zululand Safaris, who pioneered professional hunting in South Africa. At 19, he was taking clients out for rhino. Five years later he was on his own. Today, he’s a large man, dapper and dashing at 50 – with three fine sons as well, Richard, Sean and Cullen, brother Brian, a cadre of top PHs, and the finest of Zulu trackers — 31 years in the business, with hunting concessions to dream about.

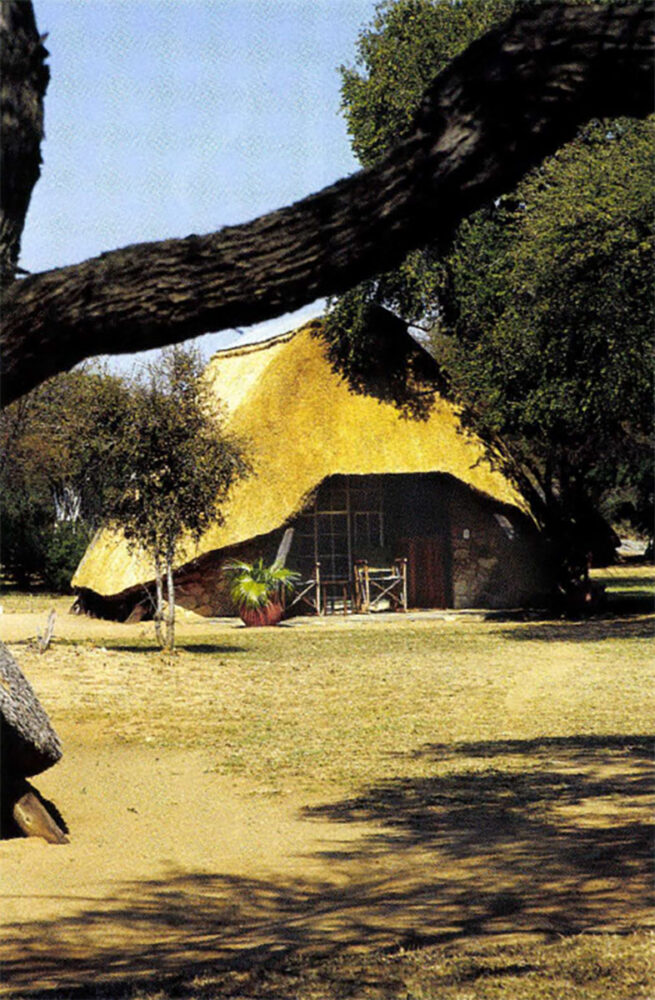

Bonwa Phala, Zulu for “where the impala drink,” is 18,000 acres of South African high-veld southeast of Johannesburg, near Warmbaths. It’s homebase for Kelly, offering distinguished, modern lodging or tent-camping, carving out well the niche between old Africa and new, ‘wild Africa and the Africa of amenities western clients have come to expect. The lodge, attended graciously by Vicky Merrett and her staff, rambles under a thatched roof through dining room, veranda and lounge, into the traditional boma. Neighboring chalets serve genially as living quarters.

A showplace of private game ranching, the property nurtures a plenitude of plains and bush animals, dangerous game including gold-class rhino and buffalo. From the lodge, it’s a handy distance to the expansive, free-range of Borokalolo National Park, for exceptional waterbuck, kudu, sable, eland, impala and warthog. And the Mkuze Game Reserve, only one of three parks in Africa providing free-range white rhino, with the world’s best nyala to boot. Or down to the Eastern cape for great mountain reedbuck, east cape kudu, springbok and cape bush buck. Plus outstanding private ranch affiliations, like Boschveld, with its tremendous kudu.

It is on Bonwa Phala the second morning we’re thwarted once more at impala, by a “go-away” bird, a gray lourie, and his incessant waahhec, waahhec. The African paradigm of a jaybird.

“Would that burrd ‘ave gone any longer, I wou’d ‘ave shot ‘im ,” Garry fusses.

Mid-morning we climb into a machan, above a waterhole. In a Tomita tree. Garry stabs the bark with his knife and we watch the milky, poisonous sap rise and bead. Around us is the whooping chuckle of the doves. Impala, warthog, zebra, nyala and kudu come and leave. None, quite, to shoot. But on the way to camp, I have leveled the rifle. Two kudu bulls linger momentarily at the edge of the taller acacias. Heart thudding, I have the shoulder of the larger. Again, Kelly shakes his head. Relief and regret. Mid-forties, but oh so handsome.

It’s cottage pie for lunch, fruit, fresh lemonade and a short nap, then Boschveld. “I anticipate your kudu this afternoon,” Garry says.

Little more than an hour later, two kudu cows have crossed from the bush into a pasture. I lean into the rifle on the sticks. We have stalked the six hundred yards here, are waiting for the great bull which hopefully will follow. A young one emerges point blank, blows, turns and bounds quickly away. There is another, a big one, far across the pasture. Too far. They are moving. We can hear others …when a warthog steps into the path 80 yards out, then another and another. Ipay them little attention.

Garry nudges me urgently. Whispers “Do you want this pig? He’s a very nice pig.”

“No … kudu,” I return tersely.

“Look at him,” he insists. The boar has seen us now, is trotting away. I see through the scope two great tusks, one either side of his bobbling rump. My heart set for kudu, I watch him on, afraid a shot will bugger our chances.

“Too late, now,” Garry laments. The kudu does not come. Others do, between four and dark, after the field hands leave the pastures. A dozen bulls, maybe 15. Time and again I’m down on the rifle, as Garry sighs. Until the sun incinerated and there were only the faint, smoldering pink and purple vapors of it above the smoky clouds, and we spotted him, in the company of two cows.

“That’s a good bull,” Garry said, “if we can close enough, I want you to take him.”

We could not, and he spooked, ghosting back into the bush.

“Should have shot the bloody damn hog,” Kelly said in the pregnant black journey back to camp.

I hurried off to retire, after dinner. I’ve traveled a bit now, hunted and fished a fair part of the world. Everywhere, every evening — I’ve wished the night away — longing for the morrow, that the hunt might begin anew. Never as in Africa. In Africa, I prayed, and my last prayer was for first light.

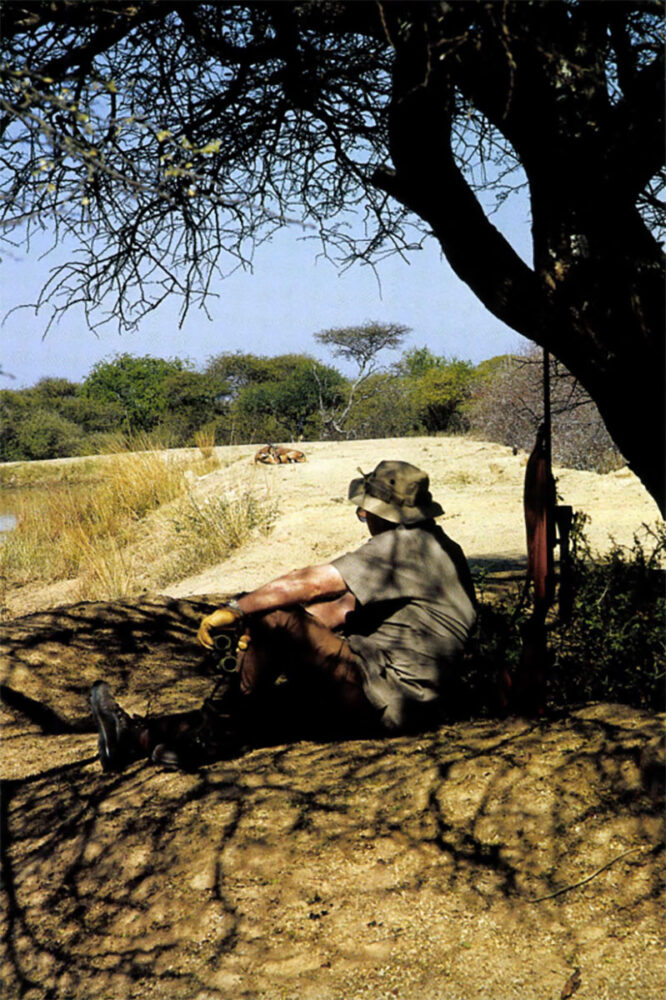

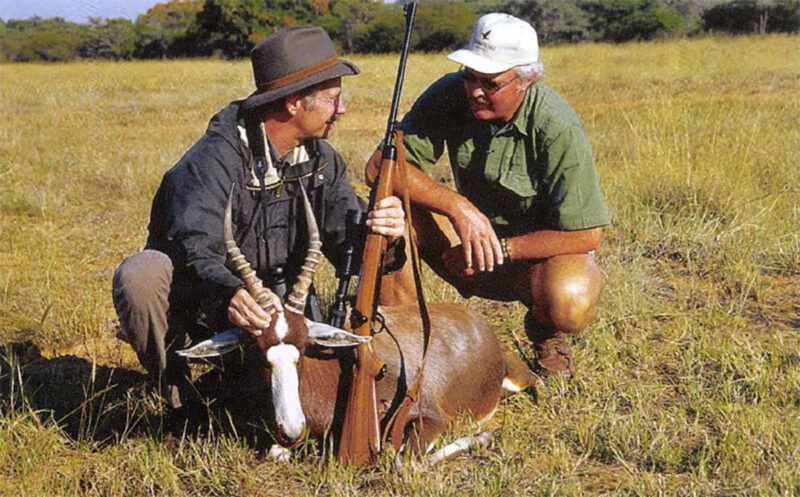

Rob Fancher waits beside a waterhole where only minutes

earlier he had downed a long-horned impala.

When it comes, there’s a hippo standing on a rock island in the Lake of the Stone Wall Dam, a bulbous cow with twin calves. Dots of white egrets blotch the dark rocks. Anhingas crowd between. Along the shore, waterbuck flee. A massive white rhino does not. Sable, zebra and wildebeest watch from the bush. All morning, a plethora of plains and lowland game have mingled with exotic bird life. The Borokalolo. But not my kudu and I am anxious for Boschveld again this afternoon.

Soup and salad and Dutch granola for lunch, an impatient doze, and we’re off. Five young bulls the first half-hour bolster our confidence, but prime time, when the great ones should be moving, there is nothing. Once more the sun expires, as we slip gingerly along the path to the water tank where yesterday we saw the big bull and his cows. He is not there.

Rob is waiting. Wearily, I shake my head. We celebrate instead his very fine warthog, and Natalie’s wildebeest. Time wears on. Tomorrow is the fourth day. What will it bring?

My impala ram, it happens. After we have ridden all morning for kudu. From the machan in the tomita tree, at the waterhole. He is a grand and sleek old fellow past breeding height, seven or eight years mature, with cluck bases and lovely lyrical horns.

“Well done, my man,” Garry said. And it had been this time.

We talked of rifles at noon. Garry showed us his working guns. A pre-64 Winchester, in .458, and a custom.375. The .458 is worn white. The tales it could tell. The one I want most to see and touch, the big Webley & Scott double, hunts with a friend.

Kelly speaks of buffalo, in the seconds between destiny and death. “Shoot himin the face, turn his head, he’ll go that way. Not in the chest. It won’t stop him.”

Of elephant. “So massive. They knot your stomach from the beginning. You never know what they will do.

“The kudu just hide,” he jokes.

Prophetically, for another afternoon at Boschveld leaves us more desperate. There was another hog, suddenly. “Shoot him,” Garry said, but he disappeared into the yellow grass. Garry waved it off with the toss of a hand. “Well, you’ve already turned down the world’s record.” There were only two kudu, as others barked their disgust from the bush. Without warning, Enoch jammed the truck to a halt, rolled out, grappled for the panga. A deft chop. A puff adder.

“Bloody damn snakes,” Garry mutters.

A big kudu bull crosses in the headlights as we wind our way out. The ride back to camp is quiet.

“It serves nobody’s justice to shoot an inferior kudu,” Carry said to me at dinner. “We’ll stay at it. We will find him. Tomorrow morning we will hunt the thick places here. We must cover much ground.

“Once again, he has my respect. And complete accord. But I cannot avoid the shiver of uneasiness that effervesces and retreats, as secretly as the kudu themselves.

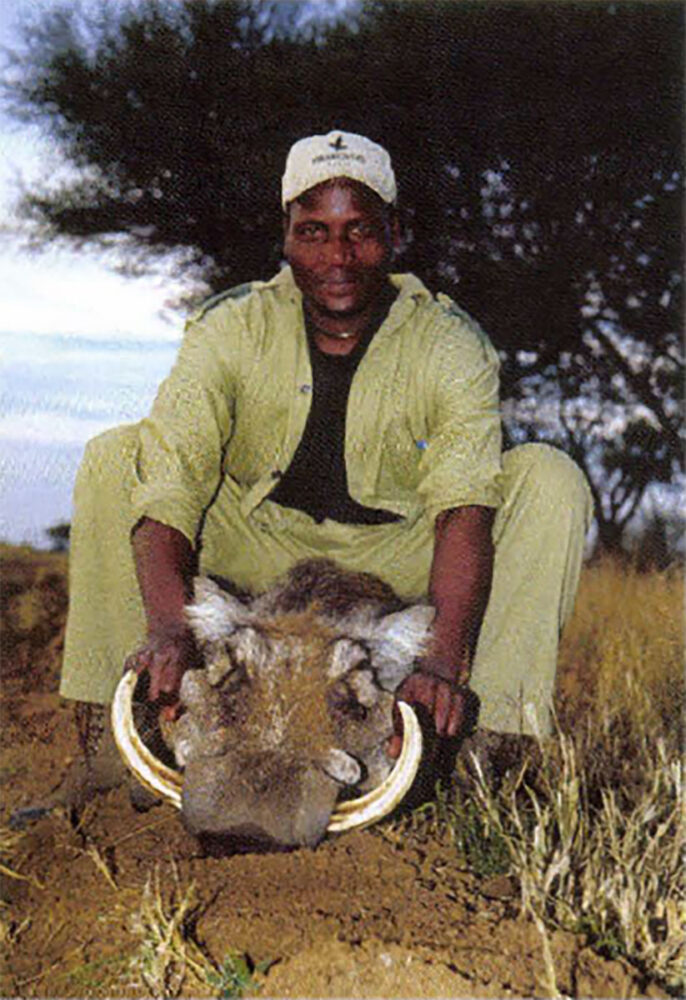

Enoch, their Zulu tracker, poses with the author’s warthog. With its incredible, 16-inch tusks, the old boar would score high in the record book.

For now I knew. They would emerge, the greatest bulls, at the deep of dusk, as if they were born of the air. A loose suggestion of molecules, that had come together in a moment, and could vaporize as quickly as it collected. A presence, a force of indefinite shape and mass, where before there was nothing. So that you wondered with yourself if even it was there. Except that you felt it oddly to the soul, as you had the ghost stories of your childhood. They came as quietly as the darkness itself, and moved so naturally with the night that they seemed not to move at all, but drift, to appear and reappear, just here and later — you thought — there. And when so often they vanished, after you had hoped, tried and failed, it was as though the very core of you had left with them.

On Bonwa Phala the fifth morning, we hope, try, and fail. Only one bull, bedded, with broken horns. With the afternoon comes another good warthog, in a scatter of sows and young. I would have shot him except he eluded ultimately the attempts of our boys to drive him by. It is at the edge of dark, that pandemonium erupts. A bull and a cow whirl and bolt. I jerk and swing, find the blade of his shoulder. Garry is hesitating and I’m beginning the squeeze. “No,” he says, “not quite. Just.”

Five minutes later, there’s no question. Our man from Boschveld stoops and points. Enoch is motioning also, with a cautious finger, across the cab of the Cruiser. Abruptly he is there — 70 yards deep — the bull we have wanted. With a blur of cows and a younger male. He has seen us, has turned and is drifting away.

“He’s big. Shoot,” Garry is pressing, “if you can get a shot at him, shoot!”

I have pieces of him through the scope, through the dense and dusky bush, desperately searching for a hole. I can’t find it, only the obscure shape and travel of him, cows milling between. He’s huge and I’m dying. If I shoot, it’s only that, just shooting. He’s faded now, farther into the bush. We scramble left, trying to find him again.

Frantically, Garry anew, “In the middle, do you have him?”

“Yes,” for a moment, amidst the tangled confusion of the smaller bull and the cows, and then they are indistinguishable. When they part ,he is gone.

Steve and Todd depart with morning for another location. Todd has followed me patiently with the camera. “I know you needed the kudu,” I told them. “Luck of the thing,” Steve said, “not for you to feel bad, but there’s a place near here kudu abound. We took Natalie there and got a 53-inch bull in one afternoon.”

I nod.

Kudu medallions adorn the dinner menu. Salvation is the flawlessness of Amarula créme liqueur, done neatly.

Not much between us through the morning. Sean simply accompanied Garry to the Cruiser come time to go. Enoch paused, lifted his eyes — in his gaze was resolve and camaraderie. Our diligence would not falter this last afternoon.

Thirty minutes into the hunt, Enoch has eased the truck to a stop. There’s a young warthog at the edge of the bush, by the path, 600 yards ahead.

I recognize the place even as Garry speaks. “We saw the big boar here the second afternoon, he may be with them.”

Enoch kills the engine. No words are spoken; it is understood. We will proceed afoot. This time I will concede.

Our stalk is meticulous. We’re standing stone-stiff now, the three of us pasted almost as one. The title is on the sticks. Thirty yards away in the high, golden grass are two pigs, now another and another. Then a sow. She has affixed us permanently, it seems, with her glare. I dread the instant she will snort and instant and the moment will shatter like glass. But finally, she is satisfied, falls back to rooting. Garry resumes his search for the boar. I catch the hump of a heavy body, moving from the bush. Gently I nudge and point.

“Him?” I whisper.

“Yes,” he affirms. The hog advances, slowly through the tall yellow thatch grass, and I am following him with the rifle, waiting for a spot. He reaches the place of tile sow, as light opening. I have only his head, for a second — the ivory either side to his ears — as he too finds us, for we are so close, and turns instantly back. But he is only wary, merely walking away. The grass parts tohis shoulder, finally, and I squeeze.

The world is mad with hogs. Hogs here, there, everywhere, in a wild dash for the bush. In the tall grass I have lost the boar completely. Reflexively I jack the bolt back, slam in another Cartridge, jerk one to the other —hoping not to find him. Then Garry is hop-skipping by me, stopping a short distance away, his face a caricature of disbelief.

Garry Kelley congratulates Mike Gaddis on his first African trophy, a beautifully marked blesbok.

“You missed the bloody damn pig,” he stammers.

“What?”

“You missed the pig,” he declares, laughing.

I notice his covetous glance at the Ruger Safari Grade rifle. He has hungered after it from the time I arrived.

“You and your shit rifle,” he says.

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Then we make our way out, the grass parts again, and there is my pig.

My eyes jump to Garry. He’s down laughing. “I ought to shoot you, you bloody Irish bastard.”

I can’t get over the tusks. It’s a hell of a pig.

“He’ll go high in both books,” Garry remarks. “Well done, my friend.”

I’m on the rifle one last time at kudu; Garry, Sean and Enoch are up with the glasses. Searching — all of us — in the final dusky moments for the bull pray be with the cows which have crossed ahead. He is not.

Dusk dies and night is born.

“Did you get the kudu?” Vicky asked earnestly of me at the lodge. “No – no kudu,” I replied.

She waited a moment. “Perhaps he is your spirit animal, and you are not meant to kill him,” she said in a soft and bloody-beautiful British/Africaans’ accent.

Perhaps. Perhaps I have wanted him too much. From the first word — the last book — there has been Africa. And after Africa — kudu.

There are times when life bestow seven the most magnificent of its creatures almost capriciously. It has never been that way for me. For that, I have learned to be thankful.

I was proud of my pig. He seemed as meant to be as the kudu did not.

So wends the timeless enigma of the hunt, even in Africa.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come.

Upon this lofty precipice, one of the most celebrated and insightful sporting authors of our time again reaches beyond himself, this time retrieving sixty-five more episodic explorations of the sporting life, the whole of which transcend contemporary perspective, and ascend to rare and unexcelled poignancy. Buy Now