There are surviving publications, most notably Sporting Classics, where my material has appeared on a regular basis for several decades.

Were I so inclined, it would be difficult to provide a whole host of examples where I played a role in putting the kibosh on start-up magazines. Off the top of my head I could name at least a half dozen that showed considerable promise, often drew contributions from skilled writers, and then ceased publication within three years. Were I a pessimist, concluding that publishing my material somehow led to miserable mojo, pending doom, or formed an outright kiss of literary death might jump to the forefront of my mind. However, there are surviving publications, most notably Sporting Classics, where my material has appeared on a regular basis for several decades.

Such thoughts meandered through my muddled mind, one readily given to tracking along tangents and exploring trails leading to rabbit holes, when some recent rearranging of portions of this hopeless packrat’s holdings unearthed issues of the ill-fated publication, Fly Fishing Heritage. I’m not sure how I linked up with the magazine, although it’s likely that the gracious hand of Nick Lyons was somehow involved. Whatever the case, the magazine lasted for a total of nine issues then, as so often happens, vanished on the whimsical winds of underfunding. I’m pretty sure not a lot of folks ever saw the publication, and given the fact that an earlier version of what follows was written well over 30 years ago, it’s likely that few if any readers of the “Daily” will have seen it. Maybe my musings on the end of another trout season as I’ve known the sport most of my life, one where you simply didn’t venture astream from November until April, will evoke some warm memories or strike resonant chords for others.

As September’s winsome song gives way to October’s spicy hints of coming harvest time, most trout fishermen harbor bittersweet memories of another season that has sped by.

To be sure, autumn offers perhaps the best angling of the year for fly fishermen in many parts of the country, but it’s also a reminder that winter, relegating us to the tying vise, vicarious angling with a good book and a comfortable armchair, or perhaps just dreams of bygone days astream, looms. This is as it should be, for fly fishing, like the passing years, is a recreation of reflection and contemplation as well as one of active participation. This was brought firmly home to me in a summer now long gone, and it occurred to me that some of the myriad thoughts it evoked might be worth sharing.

For me this was a special summer. Thanks to a mingling of circumstances, I spent more of the late spring and summer months on streams in my cherished highland homeland of the Great Smoky Mountains than I had since adolescence. Some might be inclined to condemn these magical hours and days passed in quest of trout as being at once idle and devoid of the measurable productivity that our fast-paced world seems to demand. Perhaps they were, but any misguided soul with a mindset of this nature is in my view deserving of little save pity. Sadly theirs is a world that finds them entangled in the toils of materialism as well as being ignorant of the manifold blessings one may enjoy while wielding the magic wand known as a fly rod in an especially beloved stretch of water. With such thoughts in mind, what follows is a brief attempt to convey something of what fly fishing means to me and what I think its appeal is to legions of similarly bewitched devotees.

First and foremost, I would insist that hooking and landing a trout is almost incidental. To anyone who has never been bedazzled by the necromancy that is our sport, such a statement may seem inane if not an outright lie. Yet assuredly it is true. Indeed, with passage of years and as one becomes a more accomplished angler, the verity of this conviction gleams ever brighter through the windows of a fly fisherman’s mind. He comes to realize, as have his worthy predecessors from “The Dame” and Izaak Walton onwards, that the actually landing of a trout is but one small part of a lastingly glorious experience.

There is the rhythmic visual poetry inherent in the interaction of rod and line, leader and fly. It is a joy to behold when watching a master wields his wand and pure delight when the mastery is one’s own. Furthermore, there is something about working clear, pure waters in close communion with nature’s ever-changing yet changeless beauty that brings peace and contentment to the unquiet soul. A troubled mind and a day astream are, quite simply, mutually exclusive.

In fact, every fly fisherman sooner or later discovers a truism that lies at the heart of the sport’s appeal — one cannot be perpetually worried and burdened by worldly cares if he truly immerses himself in the angler’s art. At some point, after a sufficient number of tiring yet contented hours working flies through riffle, run, and eddy, you discover that physical fatigue’s welcome partner is mental well being.

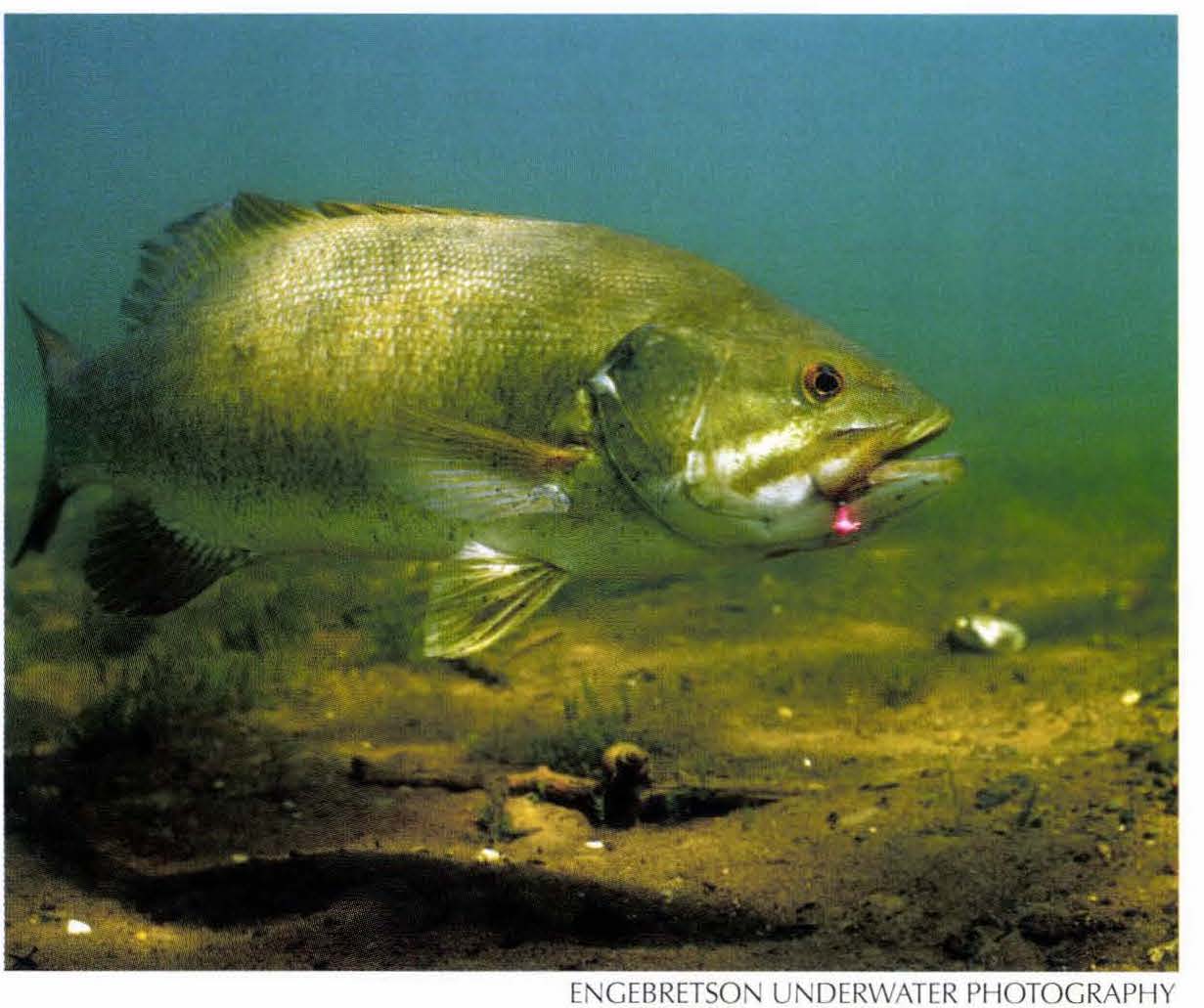

Then too, there are those precious moments that fly fishing permanently etches in the mind’s storehouse, awaiting resurrection in delightful dreams of the worlds we have lost. Here, for once, I disagree with that amiable sage of our pastime, Izaak Walton. One of his oft-quoted statements is “No man can lose what he never had.” Yet I have a special claim on not one, but several trout, along with a lordly silver salmon and a sprinkling of smallmouth bass, that I never landed. They are firmly implanted in my memory. I can still envision a beautiful rainbow’s final, freedom-winning surge and the deep runs of a mammoth brown that eventually frayed my leader on a jagged rock at least as clearly as their lesser mates that eventually were netted. Nor is it essential that big fish be involved. I remember fondly a ten-inch trout leaping a good foot out of the water to inhale my fly as it dangled from an overhanging limb to which my wayward cast had carried it. In fact, such moments need not be, though they normally are, associated with the actual act of fishing.

I will always cherish a drama I saw unfold on a remote stretch of one of my favorite streams. The raucous cry of a kingfisher lifted my eyes skyward just in time to see the bird make a dive. A small trout rewarded his keen vision and aerial acrobatics. Similarly, the spawning movements of big brown trout, singularly oblivious to my futile efforts to attract their attention with all sorts of flies, have a lasting appeal. Perhaps the most notable of all such moments of serendipity came at daylight one morning as I was rigging up. I caught movement out of the corner of my eye and watched, enchanted, as a mother mink ferried her kits, one at a time, from one side of the stream to the other. Evidently they were too small to deal with the considerable strength of the fast-moving water.

For all that sort of magic though, any angler who claims to be such a purist that the taking of trout is strictly incidental either has a pronounced penchant for dealing in untruths or else has become hopelessly confused regarding his ultimate goal. We fly fish to catch trout, and we enjoy (or at least have the opportunity to enjoy) a special satisfaction denied the hunter. The kill, sad though it may be amidst the sweetness of triumph, is a vital part of the shooter’s experience and an act of undeniable finality. The angler, by contrast, can emerge victorious and release his quarry to live and perhaps fight another day.

Arnold Gingrich, who in my view ranks as one of America’s finest angling writers, may have gone a bit overboard with what he styled “20-20 fishing” (catching 20-inch or larger trout on size 20 or smaller flies), but undoubtedly there is a special appeal in being able to stack all the odds in favor of the fish, then, in rare moments of prevailing against those odds, to display the magnanimity of victory by easing an exhausted fish back into his watery haunts.

Skeptics sometimes suggest that this special kind of affinity with the trout—the fish is your foe yet also the focus of a loving sporting relationship — smacks of elitism. I vehemently disagree, and would further contend that fly fishing has for too long been depicted as the sole preserve of elitists and those of considerable affluence. While it is true that the finest of fly fishermen are gentlemen (in the true sense of the work, they are gentle men), their material circumstances are of little or no consequence.

Eloquent testimony supporting these truths comes from my personal interactions with fly fishermen I have known over the course of a lifetime spent wading the streams of the Great Smokies. Many have waded and worked their last earthly run and gone on to piscatorial paradise, but none could, even in the wildest flights of fancy, be described as an elitist. Economically speaking, most ranked somewhere between being impoverished and of decidedly modest circumstances, several had little formal education, and none was exceptionally articulate. I grew up poor yet my father was a devoted fly fisherman. Similarly, the finest hand with a fly rod I’ve ever known lived his entire life skirting around the edges of poverty. Yet all were rich, thanks to having managed, through many years encompassing countless hours astream, to arrive at something approaching oneness with trout.

For such fortunate individuals, and they are found throughout the fly fishing world, filled creels, bragging limits, trophy fish, or 50-fish days mean nothing in and of themselves. What is important to this breed of angler, and what is so devilishly difficult to convey in print, is the overall nature of the experience. Men of this ilk recognize, each in his peculiar way, that they have achieved a satisfying degree of mastery in an activity combining art and science. Theirs is a lonely pursuit — fly fishing is in its essence a solitary sport — but in the inner recesses of their minds they enjoy the same sense of accomplishment and creativity felt by a master musician working his instrumental wizardry or a gifted painter bringing life to a canvas.

I can never aspire to be as capable an angler as two or three men I have known. Yet I am their equal in the sense that the lure of trout, the appeal of the sport they have come to cherish, is mine to share. These quiet, contemplative men have known, in their innermost being, a self-satisfaction and quietude forming integral parts of the fly fishing experience. In the end, it is rewards of this type, rather than mercenary concerns with image, equipment, or a bulging creel, that give the quest for trout true and lasting meaning. Pleasure, in short, comes from participation, and all of us are fortunate that there are waters, still in surprising abundance, where a man, whatever his means, may fish for trout. Those are comforting thoughts to carry in the mind’s creel at season’s end.

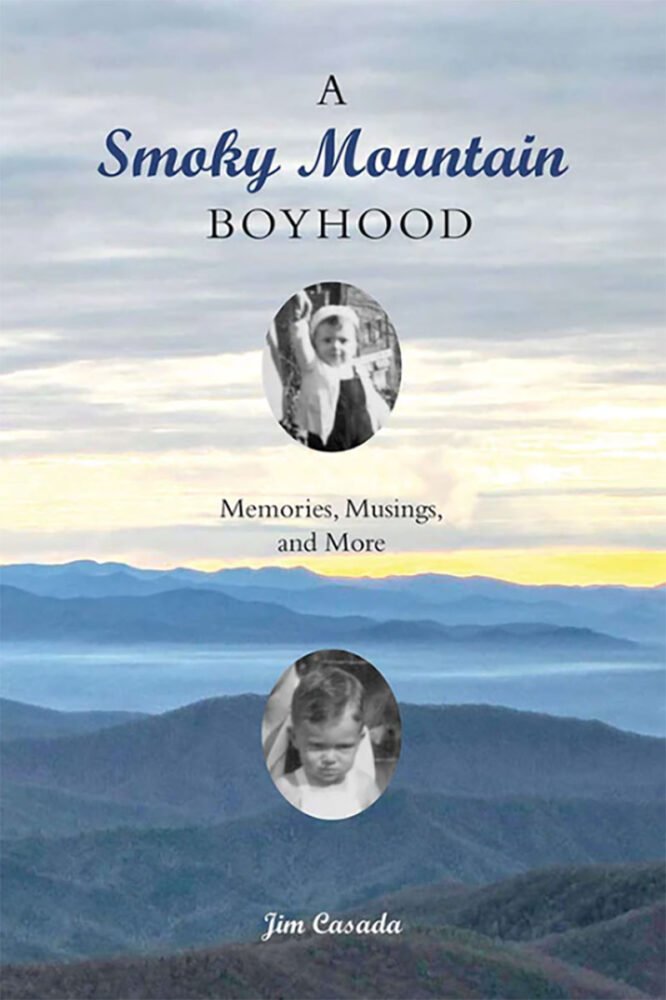

Born in Bryson City, North Carolina, Jim Casada has had a long career as a teacher, author, and avid outdoorsman. He grew up in a time and place where families depended on the land and their community to survive. Many of the Smoky Mountain customs and practices that Casada reflects on are gradually disappearing or have vanished from our collective memories. Buy Now

Born in Bryson City, North Carolina, Jim Casada has had a long career as a teacher, author, and avid outdoorsman. He grew up in a time and place where families depended on the land and their community to survive. Many of the Smoky Mountain customs and practices that Casada reflects on are gradually disappearing or have vanished from our collective memories. Buy Now