We’ve all heard about something called the “second rut,” but is it a real thing? Here is the science of the second rut.

From the National Deer Association: I hit the grunt call three times, and within minutes a nice mature buck jumped the fence and came in with his ears laid back in search of whatever buck just made that sound in his area. He was focused just like a rutting buck in November, but this was Christmas Eve, well beyond the peak of the rut. Could it be? Is this the mythic “second rut”? What is the actual science behind this idea?

The second rut is a spike in deer breeding behavior about a month after the peak of the main rut, when unbred does cycle back into estrus. This has been a controversial topic for many years among hunters. Some say there is no such thing as the second rut, others believe in its occurrence, and still others say it is just a continuance of the main rut when doe fawns are finally big enough for breeding.

How would you even know if a so-called “second rut” is happening? Look for the signs. Are there new rubs, new scrapes, old scrapes reactivated, bucks chasing does again? A Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries study showed a second peak of buck activity occurred at active scrape sites about one month after primary scrape activity during peak breeding, which would indicate there is at least “something” going on to make bucks leave sign that late in the year. You can also use trail cameras to help you determine if there is a second rut by simply documenting a change in the number of buck photographs you get.

Why is it Happening?

My toddler likes to ask me this question way too much…”But, why?” Why does this second spike in breeding activity occur?

A University of Georgia study in 1987 found that unbred does can actually experience up to seven estrus cycles if they are not bred… seven! So, based on that study, it is at least a possibility that some does that aren’t bred in the first window could potentially cycle again 28 or so days later causing a so-called “second rut.” There’s a crazy possibility that there could be more if the majority of does in an area remain unbred during each estrous cycle. That’s unlikely, since the natural rhythm of our seasons (and thus times of limited food) prevents late-born fawns from surviving in most of the United States and Canada; and even button bucks have been documented breeding does, so does are likely going to be bred within the first or second estrus cycle.

Then, there’s the doe fawns that are coming into estrus for the first time. Research has shown that doe fawns have to reach a certain size, approximately 70 to 80 pounds, before they are ready to breed. There is no way of determining when exactly a doe fawn will reach that threshold, but, it does mean that the fawn had to either be born early enough in the year to be able to reach that size for breeding or have access to ample nutrition during her first year. When Quality Deer Management is implemented in an area, the fawns will reach a size large enough more regularly for this to occur. Data from numerous studies have shown that doe fawns that do come into estrous their first year usually come into heat later than the adult does in the area.

What Can You Do About It?

There are always exceptions to the “rules.” Sometimes, the doe:buck ratio is out of balance, and there are just too many does for the local bucks to breed in a short timeframe. Another early study addressed this by trying to determine the effects of harvest strategies on the timing of the breeding season and whether or not that impacted the productivity of the deer herd. The Mississippi State University researchers concluded that it may be advantageous for areas which were “harvesting bucks only” to consider alternative management practices to shift to earlier peak breeding dates. They found that heavy pressure on bucks without doe harvest created an environment where the rut was occurring later than average, and that areas that practiced QDM had “median breeding dates that averaged two weeks earlier than areas that were buck-exploited.” This helps show that the doe:buck ratio absolutely matters when it comes to what you as a hunter observe for rutting activity, and that you should try to keep it balanced by harvesting the right number of bucks AND does or it will have a negative effect on breeding dates.

Since we now know that the timing of the rut is important for determining herd management and can play a role in your success, what should we do about it as managers? A third study used data from 16 areas in three states and confirmed the importance of collecting reproductive information for each property or management area. This allows us to identify the most critical factors affecting the timing of the rut. You shouldn’t generalize what is happening in your region or state and relay that to where you hunt. Collect data to aid in determining greatest deer activity, breeding behavior, signpost activity, and more from year to year. Observation data can enlighten you on population measures such as sex ratio, fawn recruitment, and if the proportion of mature bucks is increasing. Reproductive information can be obtained by collecting harvest data through measuring fetuses from does harvested in the late season (in areas where does can be harvested late enough to obtain measurable fetuses). Fetuses can provide a great deal of information to the hunter like date of conception, range of conception dates, peak of the rut based on conception dates, and whether a doe was bred during her first cycle.

How Hunters Can Capitalize

Regardless of whether or not the “second rut” is the correct way to describe this time period, we do know there is an opportunity for hunters to capitalize on this secondary spike in breeding behavior. This might be the time to finally catch up to that buck you’ve been chasing all season, especially if you missed your opportunity during the peak of the rut. Calling, rattling, and scent lures can be used again to try and bring that buck within striking distance.

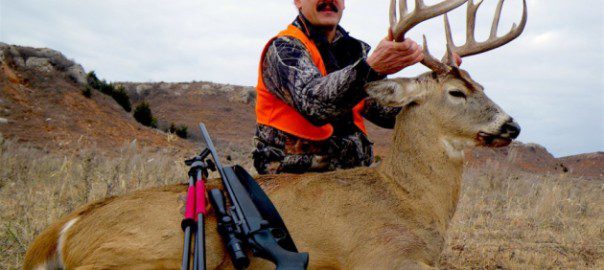

I was able to have some great success using a grunt call during this time when hunting in South Arkansas several years ago. The rut in this area typically peaks around Thanksgiving, but this was the day before Christmas when we went out for a Sunday afternoon hunt. I got set up in my treestand at 2:00 p.m. and hit the grunt call three times. Within minutes, a nice mature buck jumped the fence and came in with his ears laid back. He was focused, just like a rutting buck in November. By 2:15 p.m., I was on the ground field-dressing the buck after dropping him with my muzzleloader.

Whether you call it the second rut or something else, it’s just another good reason to be out there in the woods! The science shows there is definitely something going on out there! Good luck and happy hunting!

By: Cheyne Matzenbacher, NDA Deer Outreach Specialist

There’s something special about the deer hunters of yesteryear. Seeing rare images of snowy campsites, straining meat poles, classic rifles and the happy faces of the men and women who plied their trade so long ago connects us to those treasured times like nothing else in the world can do.

There’s something special about the deer hunters of yesteryear. Seeing rare images of snowy campsites, straining meat poles, classic rifles and the happy faces of the men and women who plied their trade so long ago connects us to those treasured times like nothing else in the world can do.

With the enormous popularity of the original Dawn of American Deer Hunting published in December 2015, author Duncan Dobie and Sporting Classics now bring you Volume II, chock full of amazing stories and facts, a breathtaking color section filled with eye-catching whitetail art and nearly 400 stunning black-and-white photos. Buy Now