A scent can conjure up emotions and even specific memories. In the brain, smell is the closest to memory; in the heart, the closest to love.

She meditated. She would not eat the venison I brought her. She worshiped some Hindu holy man whose name I wish I could forget. She was part Choctaw, and likely part Hawaiian too, in which her name translated “beautiful running water.” Hazel eyes, high cheekbones, delicate little nose with the slightest flare at the nostrils, a fine tangle of dark hair that hovered around her face like a halo. I reckoned her some sort of minor goddess. She wore frangipani perfume and she left a scent trail wherever she went.

Way up north in Minnesota, half a lifetime ago.

I was spinning wrenches in those days— exotic cars, Jags, Porches, Triumphs, and please don’t get started on Peugeot diesels for which you had to drop an intake valve atop a piston and read the run-out with a dial indicator to set the injectors. Women involved sometimes. Locals laughed and called me The Organic Mechanic.

She drove a Volvo 122 wagon, twin side-draft SU carburetors that wouldn’t idle. She dropped it off after hours, her skydiving logbook and a single red rose upon the passenger seat.

Mark Twain pegged it perfectly. “Some men can resist temptation if the woman lacks in attractiveness.”

She cost me four good years, half a farm and a hundred grand, but I will never complain. She wove me a hot pink and electric-arc blue hook rug when she was on some God-help-you pilgrimage to India; the color of my aura, she said. Cards on my birthday, Christmas and Easter for the next 40 years, Minneapolis postmark, no return address. And when the cards finally quit coming, I reckoned she was dead.

If I ever get a whiff of frangipani again, I’ll break right down and cry. And if I ever smell it in heaven, I’ll smile.

The closest sense to memory, the closest to the heart.

The neural code begins with the nose’s sensory neurons. Once an odor molecule binds to a receptor, it initiates an electrical signal that travels from the sensory neurons to the olfactory bulb, a structure at the base of the forebrain that relays the signal to other brain areas for additional processing.

One of these areas is the piriform cortex, a collection of neurons located just behind the olfactory bulb that works to identify the smell. Smell information also goes to the thalamus, a structure that serves as a relay station for all of the sensory information coming into the brain. The thalamus transmits some of this smell information to the orbitofrontal cortex, where it can then be integrated with taste information.

“A scent can also conjure up emotions and even specific memories. This happens because the thalamus sends smell information to the hippocampus and amygdala, key brain regions involved in learning and memory.”

Like the spiritual beat out on the bare pine floors of the old Negro country churches, “the foot bone connected to the leg bone, the leg bone connected to the thigh bone…”

Big Al Orsund was too young for the first war, too old for the second, but prime ripe for the Great Depression when he served as a master sergeant in the Civilian Conservation Corps, overseeing windbreak plantings, trying to keep the Dust Bowl out of North Dakota. It worked.

Big Al retired to a sugar bush on the west side of Otter Lake, a mile-long glacial cleft through the Minnesota hills, ten feet deep at the north end, 90 at the south where the glacier really got rolling. The lake had bass, panfish, a few walleyes, even fewer giant and toothy northern pike, most taken in midwinter with a spear, not hook and line.

Butch Kratzke lived on the east side and had a cousin who worked for the fish hatchery. Sometime in the mid-’50s, he struggled a milk can of fry down to the water and all those four-foot pike were descendants of that single load. Otter Lake kept the woods cool, and Big Al’s sugar maples were shaded from the pewter sun, still way down the southern sky, even at noon. They were last to run sap thereabouts, which was good as we could ice fish right up to sugaring time.

Wade the slush at lake edge, push a 12-foot Jonboat like a sled, ready to leap aboard should the ice give way and sometimes it did. Thirty feet out onto the ice, you might reasonably assume you would not drown, but we carried sawed-off ice picks strung on lanyards around our necks just in case, one pick close to each hand to jab in the ice and claw our way atop once again, back to the land of the living. Nobody wanted his last drink to be lake water. There was a judicious application of medicinals: Copenhagen dip, ditch-weed marijuana, Windsor Canadian, De Kuyper’s peach, and peppermint schnapps. Nothing so fine as panfish from water so cold even the largemouth bass taste good. But I digress.

Twenty-six degrees, 28 at three a.m., rising to 30 each noon and up on the hill the sap was starting to run—a steady drip, drip, drip into ten-quart pails, metallic tinks in the mornings, melodic ploops in the afternoons. One hundred-odd taps, one on smaller trees, two on the larger ones, brass spigots driven into holes hand-drilled into the living wood.

We worked the sugar bush with a 1948 Allis Model C with a two-wheel trailer, the running gear from a Model A Ford pickup. Firewood in the fall, maple sap in the spring, venison whenever we had a deer down, which was often, the old tractor came in mighty handy. You never junked nothing in those days. Make it do, wear it out, do without.

The Ford 8-N has killed more men than the Philippine Insurrection and the Second Nicaraguan Incursion combined, the John Deere B in second place. But the Allis wouldn’t tip on the sidehills and was too weak to rear back on flat ground.

Al drove and I hauled sap, pail by pail through the last of the snowdrifts, still knee-deep some places.

Fifty gallons of sap to make a single gallon of syrup, all boiled down over a fire of oak, birch, and ironwood cut from among the maples, a half-cord burned per each gallon bottled, a rick of firewood four by four by four—1,620 pounds more or less. Ye shall earn your bread by the sweat of your brow, the Good Book says, and never was it truer than in the sugar bush. We sweated plenty, me and Big Al, even in March.

We fired the boiler in the chill of the evening when the moon crept up the eastern sky, round and bright as a silver dollar, and the aurora shimmered and crackled off to the northwest, and the wolves took to yodeling way back in the big woods. The whiskey came around, the fire roared, the sweet steam rolled, and we would have syrup by sunrise.

Hippocampus and amygdala all over again, the nose bone connected to the head bone, and I was forever in love with the sugar bush, with the smell of woodsmoke and the sweet boiling sap. Smell is the closest sense to memory, the closest to love.

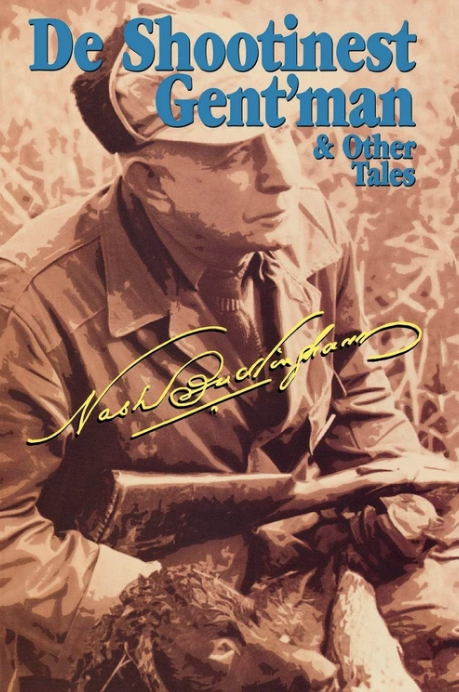

This collection of eight stories first published in Field and Stream, Recreation, and Outdoor Life was originally published by The Derrydale Press in 1934.

This collection of eight stories first published in Field and Stream, Recreation, and Outdoor Life was originally published by The Derrydale Press in 1934.

Travel with Nash on some of the most heart-warming experiences ever put to paper by an outdoor writer. In the dead of winter by a nice fire in your favorite chair, get ready to relive some of the best hunting stories ever shared by America’s finest outdoor author—Nash Buckingham. Buy Now