‘Twas the night before Christmas in the old cabin, and the two trappers had just settled in when what to their wandering eyes should appear…

“Talkin’ about Christmas,” said Bedrock, as we smoked in his cabin after supper, an’ the wind howled as it sometimes can on a blizzardy December night, “puts me in mind of one I spent in the ’60s. Me an’ a feller named Jake Mason, but better knowed as Beaver, is trappin’ an’ prospectin’ on the head of the Porcupine. We’ve struck some placer, but she’s too cold to work her. The snow’s drove all the game out of the country, an’ barrin’ a few beans and some flour, we’re plum out of grub, so we decide we’d better pull our freight before we’re snowed in.

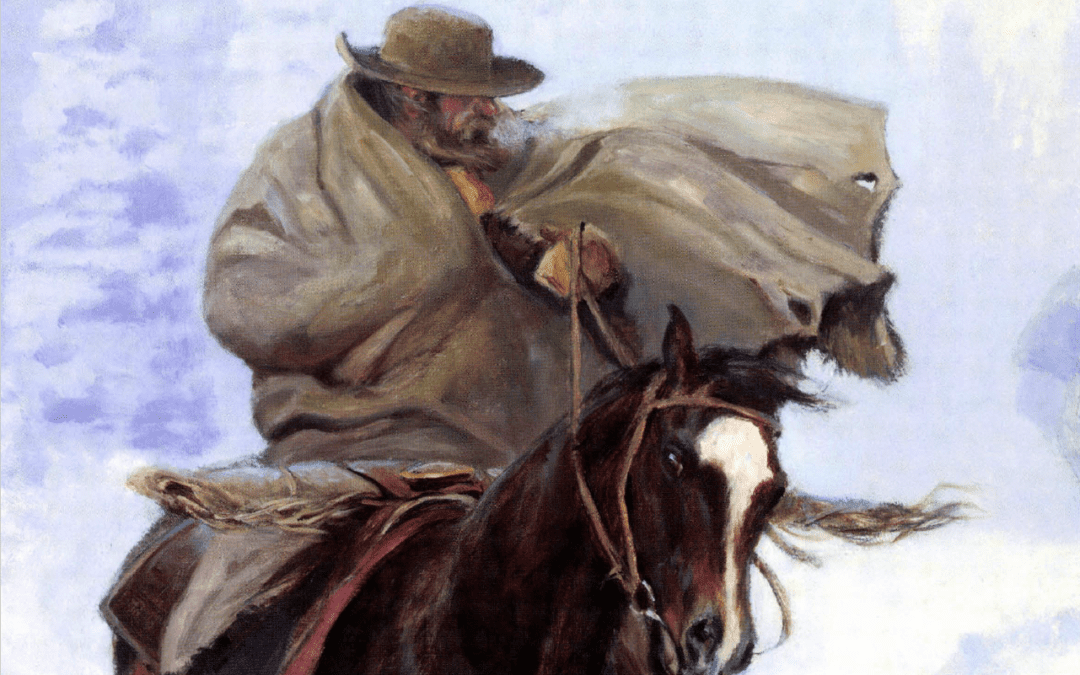

“The winter’s been pretty open till then, but the day we start there’s a storm breaks loose that skins everything I ever seed. It looks like the snow-maker’s been holdin’ back, an’ turned the whole winter supply loose at once. Cold? Well, it would make a polar bear hunt cover.

“About noon it lets up enough so we can see our pack-hosses. We’re joggin’ along at a good gait, when old Baldy, our lead packhoss, stops an’ swings ’round in the trail, bringin’ the other three to a stand. His whinner causes me to raise my head, an’ lookin’ under my hat brim, I’m plenty surprised to see an old log shack not ten feet to the side of the trail.”

“‘I guess we’d better take that cayuse’s advice,’ says Beaver, pintin’ to Baldy, who’s got his ears straightened, lookin’ at us as much as to say: ‘What, am I packin’ fer Pilgrims; or don’t you know enough to get in out of the weather? It looks like you’d loosen these packs.’ So, takin’ Baldy’s hunch, we unsaddle.

“This cabin’s mighty ancient. It’s been two rooms, but the ridge-pole on the rear one’s rotted an’ let the roof down. The door’s wide open an’ hangs on a wooden hinge. The animal smell I get on the inside tells me there ain’t no humans lived there for many’s the winter. The floor’s strewn with pine cones an’ a few scattered bones, showin’ it’s been the home of mountain-rats an’ squirrels. Takin’ it all ‘n all, it ain’t no palace, but, in this storm, it looks mighty snug, an’ when we get a blaze started in the fireplace an’ the beans goin’ it’s comfortable.

“The door to the back’s open, an’ by the light of the fire I can see the roof hangin’ down V-shaped, leavin’ quite a little space agin the wall. Once I had a notion of walkin’ in an’ prospectin’ the place, but there’s somethin’ ghostly about it an’ I change my mind.

“When we’re rollin’ in that night, Beaver asks me what day of the month it is.

“‘If I’m right on my dates,’ says I, ‘this is the evenin’ the kids hang up their socks.’

“The hell it is,’ says he. ‘Well, here’s one camp Santy’ll probably overlook. We ain’t got no socks nor no place to hang ’em, an’ I don’t think the old boy’d savvy our foot-rags.’ That’s the last I remember till I’m waked up along in the night by somethin’ monkeyin’ with the kettle.

“If it wasn’t fer a snufflin’ noise I could hear, I’d a-tuk it fer a trade-rat, but with this noise it’s no guess with me, an’ I call the turn all right, ’cause when I take a peek, there, humped between me an’ the fire, is the most robust silvertip I ever see. In size, he resembles a load of hay. The fire’s down low, but there’s enough light to give me his outline. He’s humped over, busy with the beans, snifflin’ an’ whinin’ pleasant, like he enjoys ’em. I nudged Beaver easy, an’ whispers: ‘Santy Claus is here.’

“He don’t need but one look. ‘Yes,’ says he, reachin’ for his Henry, ‘but he ain’t brought nothin’ but trouble, an’ more’n a sock full of that. You couldn’t crowd it into a wagon-box.’

“This whisperin’ disturbs Mr. Bear, an’ he straightens up till he near touches the ridge-pole. He looks eight feet tall. Am I scared? Well, I’d tell a man. By the feelin’ runnin’ up and down my back, if I had bristles I’d resemble a wild hog. The cold sweat’s drippin’ off my nose, an’ I ain’t got nothin’ on me but sluice-ice.

“The bark of Beaver’s Henry brings me out of this scare. The bear goes over, upsettin’ a kettle of water, puttin’ the fire out. If it wasn’t for a stream of fire runnin’ from Beaver’s weapon, we’d be in plumb darkness. The bear’s up agin, bellerin’ an’ bawlin’, and comin’ at us mighty warlike, and by the time I get my Sharps workin’, I’m near choked with smoke. It’s the noisiest muss I was ever mixed up in. Between the smoke, the barkin’ of the guns an’ the bellerin’ of the bear, it’s like hell on a holiday.”

Hell on Holiday by Dan Metz

“I’m gropin’ for another ca’tridge when I hear the lock on Beaver’s gun click, an’ I know his magazine’s dry. Lowerin’ my hot gun, I listen. Everythin’s quiet now. In the sudden stillness I can hear the drippin’ of blood. It’s the bear’s life runnin’ out.

“‘I guess it’s all over,’ says Beaver, kind of shaky. ‘It was a short fight, but a fast one, an’ hell was poppin’ while she lasted.’

“When we get the fire lit, we take a look at the battle ground. There lays Mr. Bear in a ring of blood, with a hide so full of holes he wouldn’t hold hay. I don’t think there’s a bullet went ’round him.

“This excitement wakens us so we don’t sleep no more that night. We breakfast on bear meat. He’s an old bear an’ it’s pretty stout, but a feller livin’ on beans and bannocks straight for a couple of weeks don’t kick much on flavor, an’ we’re at a stage where meat’s meat.

“When it comes day, me an’ Beaver goes lookin’ over the bear’s bedroom. You know, daylight drives away ha’nts, an’ this room don’t look near so ghostly as it did last night. After winnin’ this fight, we’re both mighty brave. The roof caved in with four or five feet of snow on, makes the rear room still dark, so, lightin’ a pitch-pine glow, we start explorin’.

“The first thing we bump into is the bear’s bunk. There’s a rusty pick layin’ up against the wall, an’ a gold-pan on the floor, showin’ us that the human that lived there was a miner. On the other side of the shack we ran onto a pole bunk, with a weather-wrinkled buffalo robe an’ some rotten blankets. The way the roof slants, we can’t see into the bed, but by usin’ an axe an’ choppin’ the legs off, we lower it to view. When Beaver raises the light, there’s the framework of a man. He’s layin’ on his left side, like he’s sleepin’, an’ looks like he cashed in easy. Across the bunk, under his head, is an old-fashioned cap-‘n-ball rifle. On the bedpost hangs a powder horn an’ pouch, with a belt an’ skinnin’ knife. These things tell us that this man’s a pretty old-timer.

“Findin’ the pick an’ gold-pan causes us to look more careful for what he’d been diggin’. We explore the bunk from top to bottom, but nary a find. All day long we prospects. That evenin’, when we’re fillin’ up on bear meat, beans and bannocks, Beaver says he’s goin’ to go through the bear’s bunk; so, after we smoke, relightin’ our torches, we start our search again.

“Sizin’ up the bear’s nest, we see he’d laid there quite a while. It looks like Mr. Silvertip, when the weather gets cold, starts huntin’ a winter location for his long snooze. Runnin’ onto this cabin, vacant, and lookin’ like it’s for rent, he jumps the claim an’ would have been snoozin’ there yet, but our fire warmin’ up the place fools him. He thinks it’s spring an’ steps out to look at the weather. On the way he strikes this breakfast of beans, an’ they hold him till we object.

“We’re lookin’ over this nest when somethin’ catches my eye on the edge of the waller. It’s a hole, roofed over with willers.

“‘Well, I’ll be damned. There’s his cache,’ says Beaver, whose eyes has follered mine. It don’t take a minute to kick these willers loose, an’ there lays a buckskin sack with five hundred dollars in dust in it.

“Old Santy Claus, out there,’ says Beaver, pointin’ to the bear through the door, ‘didn’t load our socks, but he brought plenty of meat an’ showed us the cache, for we’d never a-found it if he hadn’t raised the lid.’

“The day after Christmas we buried the bones, wrapped in one of our blankets, where we’d found the cache. It was the best we could do.

“I guess the dust’s ours,’ says Beaver. ‘There’s no papers to show who’s his kin-folks.’ So we splits the pile an’ leaves him sleepin’ in the tomb he built for himself.”

Editor‘s Note: “Savage Santa” is from Trails Plowed Under by Charles M. Russell, © 1927 by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. Used by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc.

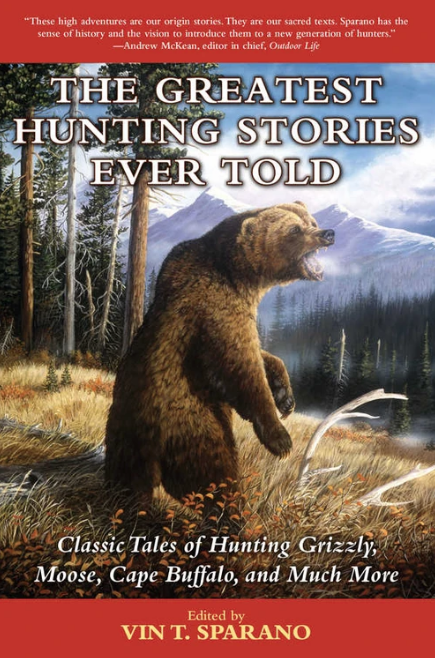

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Included here are the experiences of Teddy Roosevelt in “The Wilderness Hunter,” of Jack O’Connor in “The Leopard,” of J. C. Rickhoff in “Wounded Lion in Kenya,” of Frank C. Hibben in “The Last Stand of a Wily Jaguar,” and of John “Pondoro” Taylor in “Buffalo,” among others.

Collected by a lifelong devotee of hunting literature, the stories here are classics. In more than two dozen selections, the true experiences of hunting a variety of animals are relayed by the most reliable eyewitnesses: the hunters themselves. A must for all hunters and armchair adventurers, The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a real trophy. Buy Now