Life is short. Perhaps that is why a worn 1976 Georgia license plate reads “RUFF61” as a reminder of the most glorious and magical season a mortal man could ever hope to experience. Hunting almost every day and bringing down 61 of those beautifully explosive and sacred brown rockets with confidence and precision and that “I’m going to live forever” mindset, 1975 had been Sam Fite’s best season ever. Not that totals really made much difference to him. It was the number of days in the woods and the number of hours spent with ol’ Rip, one of his finest and most beloved bird dogs, and following Rip through some of his favorite mountain bottoms along hemlock and rhododendron thickets that really mattered. It was the closest thing to heaven on earth a man could ever hope to achieve.

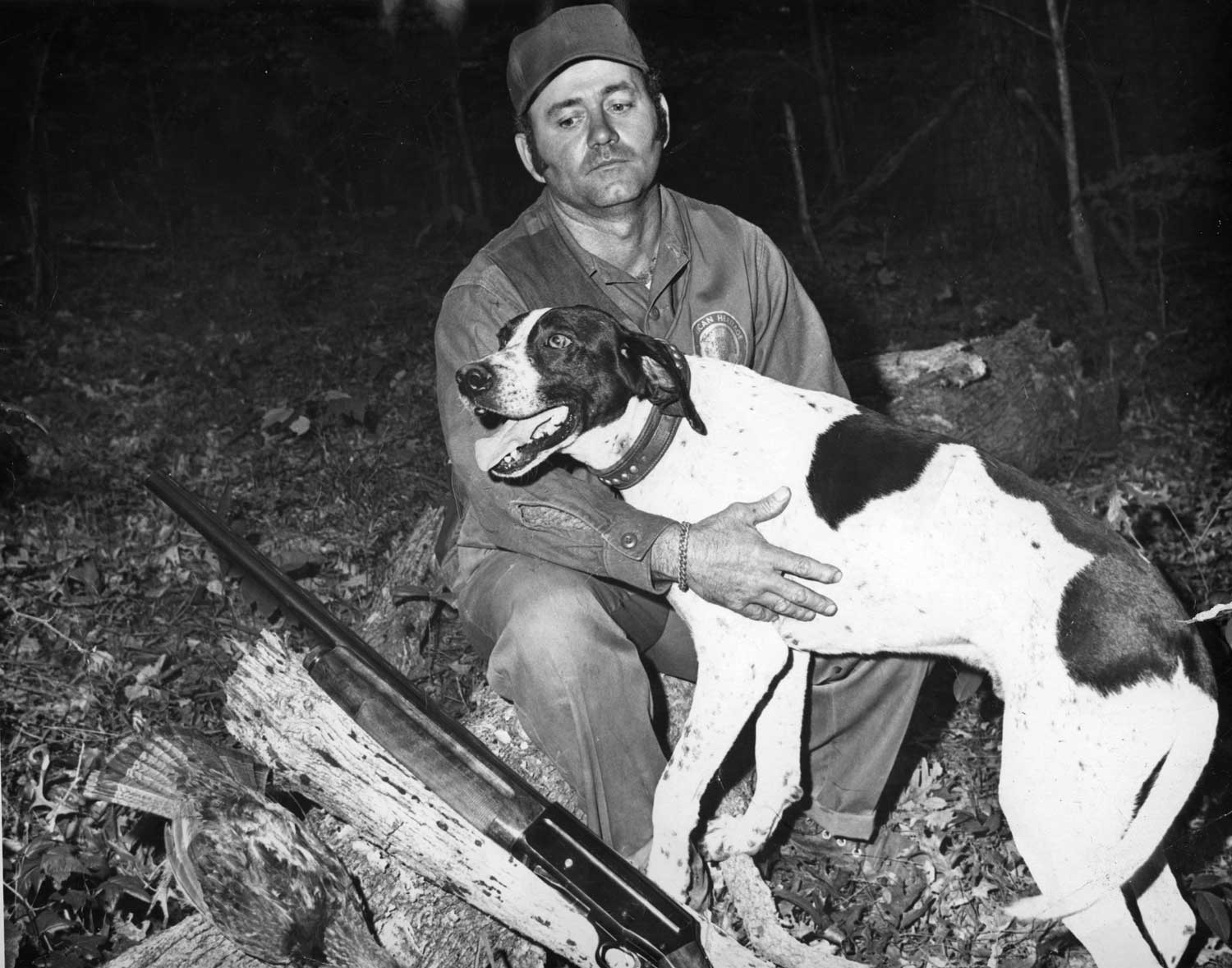

Sam with one of his best, all-time grouse dogs — a beloved pointer named Rip. Many a happy mile was traversed by this inseparable dynamic duo, and many a grouse fell to Sam’s gun. Photo circa 1980s.

In the old days, there was always next year. But then the all-too-quick seasons that once seemed tolerable suddenly began to rush by like a run-away locomotive. We’re only allotted so many days until, finally, one day, those once strong and sure legs, legs that had ventured countless miles traversing venerable Georgia hills and crossing rich hollows and thick bottoms where proud rock chimneys from another time still stood as silent sentinels, couldn’t be depended on any longer. Then, too, when the day finally arrived that ol’ Rip closed his eyes and went to sleep for the last time, the pain was almost unbearable.

Not only is Sam “Bird” Fite a seasoned veteran, he’s also a seasoned backwoods philosopher. Any man who loves his chosen avocation with as much passion as he holds in his heart can’t help but become a philosopher. Seven decades of chasing the “big three” in North Georgia molded him into a passionate as well as highly compassionate bird hunter. Sam’s big three — quail, turkeys and grouse — were his reason for living, but grouse were his life. They stand out above all else like a blinking neon lights — having been his obsession and his life’s quest since his early teens when he shot his first bird and had no earthly idea what it was. But he quickly found out and he quickly became a master. If grouse hunting were an Olympic sport, Sam Fite would have been an international gold medalist many times over.

Now a thoughtful 87, Sam is able to look back and reflect on a life well spent in the woods. I hesitate to call Sam an “old timer” because he is so young at heart, he’s so down to earth, but Father Time has a way of catching up with all of us.

Now a thoughtful 87, Sam is able to look back and reflect on a life well spent in the woods. I hesitate to call Sam an “old timer” because he is so young at heart, he’s so down to earth, but Father Time has a way of catching up with all of us.

“Time was when I wanted to shoot every grouse out there,” Sam says. “Now I’m beginning to wonder why I ever wanted to kill even one. I love those amazing creatures. They’re the most beautiful game bird the Good Lord ever invented.”

If a man is lucky enough to hunt long enough, this sense of deep adoration and respect frequently afflicts veteran hunters. They grow to so deeply revere the deer or turkeys, or in Sam’s case — the grouse — they’ve been chasing for so long that one day the desire to draw blood begins to diminish. You can take the hunter out of the woods, but you can never fully take the woods out of the hunter. In Sam’s case, there were a few extenuating circumstances.

“I can’t walk anymore,” he says. “My legs are shot. I used to think climbing to the top of a mountain in North Georgia was akin to walking across a parking lot at Walmart. Not anymore.”

Stage IV colon cancer didn’t help any either. Almost always a death sentence, Sam miraculously beat this deadly cancer despite the odds. He’s been cancer-free for more than 12 years now, but there have been inconveniences. Being alive certainly beats the alternative.

But the real reason he threw in the towel is because of dwindling bird populations.

“The grouse are near gone,” he says. “Nowadays, you may go all day without seeing a single bird, and that’s using a top dog. If they were still there, I’d find a way to go after them. I’d drive my old truck to the edge of a cutover and I’d find a bird or two. I can still shoot. I just can’t walk. Maybe I could crawl ’em up like I used to do with ol’ mountain gobblers.”

Sam’s not exaggerating. He literally “crawled up” a number of fine high country longbeards. In his heyday, he often hunted turkeys by sitting in a brush blind and waiting until they walked by. Mountain hunters make their own rules.

It’s now been a good six or seven years since Sam has been in a grouse covert with a shotgun in his hand and a well-trained dog leading the way. That may seem sad but he’s not complaining. He still loves to go back and drive around to some of his familiar haunts. The mountains are in his blood. He long ago moved to the outskirts of Atlanta to make a living, but he can’t go for long without physically being surrounded by mountains on all sides. Only then does he really feel alive. And whenever he feels a little melancholy, the myriads of memories are there to brighten his day. They’re as vivid as a summer rain beating down on a tin roof.

“Can’t nobody ever take that away,” he says. “I can close my eyes and put myself right there, smell the scent of falling leaves on an old logging road and see the sudden colors that seemed to come about overnight, the yellow maples, the red oaks. I can see ol’ Rip with his nose up, working that bottom, weaving back and forth like a heat-seeking missile honing in on its target. It was pure joy to watch him. He’s buried in my back yard next to ol’ Jake, ya’ know. I sure do miss ’em both. Two of the best….”

By most standards, Sam grew up dirt poor on the Georgia/Tennessee line in the shadow of the rugged Cohutta Mountains. In truth, this was a blessing in disguise because bird hunting became a way of life. Mountain folks will survive. No matter how bad things get, a mountaineer can always go out and catch a fish or shoot a squirrel. He will put food on the table.

Did I use the word poor? Having a shotgun in your hands at age 12 and being delegated by your daddy to go out and shoot something for supper — a quail, a rabbit or maybe a grouse if you’re lucky — on a regular basis may be more akin to being one of Robin Hood’s merry men in Sherwood Forest. Life was good as long as you had a gun in your hands. And for Sam Fite it was definitely a slice of heaven. Mark Twain once reminisced about his boyhood on the Mississippi by saying, “Everyone in Hannibal was poor; we just didn’t know it.” Sam has never known a poor day in his life.

His legs may be gone but his memory is sharper than a turkey spur. “I could take you to any number of cutover places I used to go in the Cohuttas or over around the Blue Ridge country and show you where this bird flushed or that bird went down. Even if I don’t have the desire to kill anything anymore, I love daydreaming about some of those wonderful hunts with some mighty special dogs I’ve owned.”

In his heyday, Sam was good; maybe one of the best ever in the Southeast when it came to grouse. If a quail or grouse flushed, he seldom missed a shot. He could read cover like a book. He instinctively knew where to put the dogs out and where they might find birds. He was a natural with a shotgun. Maybe it came from years of practice.

In 1974, he brought down 60 birds. “Pa’tridges” mountain folks like to call them. The following year, he beat that record by one with 61 birds and his 1976 license tag proudly reflected that stellar season. In ’76 he had every intention of breaking his record with more than 62. It was a personal thing. And he almost did it. But the hunting gods failed to cooperate.

“We had a fresh snow the last weekend of the season,” he remembers. “Grouse won’t flush in a new snow.” So his record remained at 61. Only one other mountain hunter killed more than 70 grouse in a single season, and that man — Arthur Truelove — is a legend in the mountain region.

Gray Ghost of the North by Greg Beecham

Nowadays Sam’s love affair with grouse and grouse hunting is reflected in everything he does. His home is a virtual museum of bird hunting memorabilia, mostly grouse. Every wall is covered with limited edition prints or paintings done by friends of grouse, turkeys and quail. Several mounted grouse and quail adorn the cabinets.

Sam’s bedroom is a time capsule of his long hunting career. A large turkey gobbler — with wings spread in the flying position — hangs over his bed on a wire. It’s a fine mountain longbeard that he mounted himself.

When he wakes up in the morning, a life-size grouse stares at him from the foot of the bed. In addition to more prints and photos, old shotgun shells and hunting gear, the room is replete with hunting quotes: “Hunting isn’t everything, but it sure beats whatever is second.” “Two old men, two old guns on a long walk back through time.” “I’ve spent most of my life hunting. The rest of it was wasted.”

On many of my hunting trips all i bring home is an odd-shaped rock, a piece of chestnut log, or a picture of some lovely mountain scene. I always bring back memories of the experience, and I’m always just as eager to go the next time. I consider it a true blessing to have been as healthy and physically able to go for as many years as i did. — Sam Fite

Even Sam’s attention-getting mailbox reflects his lifelong obsession with bird hunting. It’s a round, bright red, handmade shotgun shell with a pointer standing on top.

“If that doesn’t put you there, nothing will,” Sam says with a grin. “Sometimes when I get in or out of bed the air from my covers makes the turkey spin around as if in flight. I’ve often said the first and last things I would like to see each day is the mountains. For now, I have to make-do with the turkey.”

Whenever real mountains do come into view, Sam becomes a different person; mentally, spiritually and physically. He feels blessed to be able to spend time in the fields or along some beautiful mountain stream that “no human could possibly have made….” One of his favorite quotes is: “A real hunter can experience fatigue beyond words, see his best efforts go for nothing and still leave the woods feeling he is a lucky man.” I am truly blessed with so many hunting memories that took place in those wonderful mountains.

“I don’ remember ever hearing of, or seeing a grouse, until one flushed in front of me one day when I was a teenager,” he says. (Unlike a lot of mountaineers, Sam has always called them “grouse.”) “I was stunned. I didn’t know what it was. Once I found out, I was a dedicated grouse hunter for life. That bird flew into my heart, mind and soul and it has remained there for as long as I’ve been on this earth. An old grouse hunter once told me, ‘If in your lifetime you have one good grouse dog, one true friend and one good woman, you could count yourself a lucky man.’ He also said that to be a true grouse hunter, you had to be a little ‘tetched’ in the head. I suppose he’s right.

“My favorite shotguns are Brownings, Franchis and Benellis. When people used to ask me who I hunted with, I would answer, ‘Why Mr. Smith, of course.’ Some days I would hunt half of the day with my L.C. Smith and change at lunch to an automatic. My brother Frank would use my L.C. Smith in the afternoon. I really enjoyed using both of the shotguns. Another of my favorite dogs was named Junior. One morning as I was leaving to go to work, I ran over Junior. He had gotten out of the dog pen without me knowing it and was waiting under the truck because he thought we were going hunting. It was still dark, and I didn’t see him. To kill your own dog is the worst feeling a hunter could ever experience.”

Sam doesn’t mind being a little “tetched” in the head. For him, the memories will always reign supreme; splendid, spectacular, rich and lofty, proud and lovely.

“During all my many years of grouse hunting,” adds Sam, “I have received so much enjoyment and pleasure simply being able to share in our Lord’s beautiful mountains. To get my limit on any given day was always an added blessing. That old grouse hunter was right. I truly am a lucky man!”