If Hell was cold, wet and windy, it would probably look a great deal like Volcano Bay in Alaska’s Aleutians.

But in one of those lovely little touches of irony at which God is so devilishly good, if Heaven was made just for fishermen with a sense of adventure, the Sweet Hereafter would also probably resemble this icy, storm-battered and far-flung end of the earth.

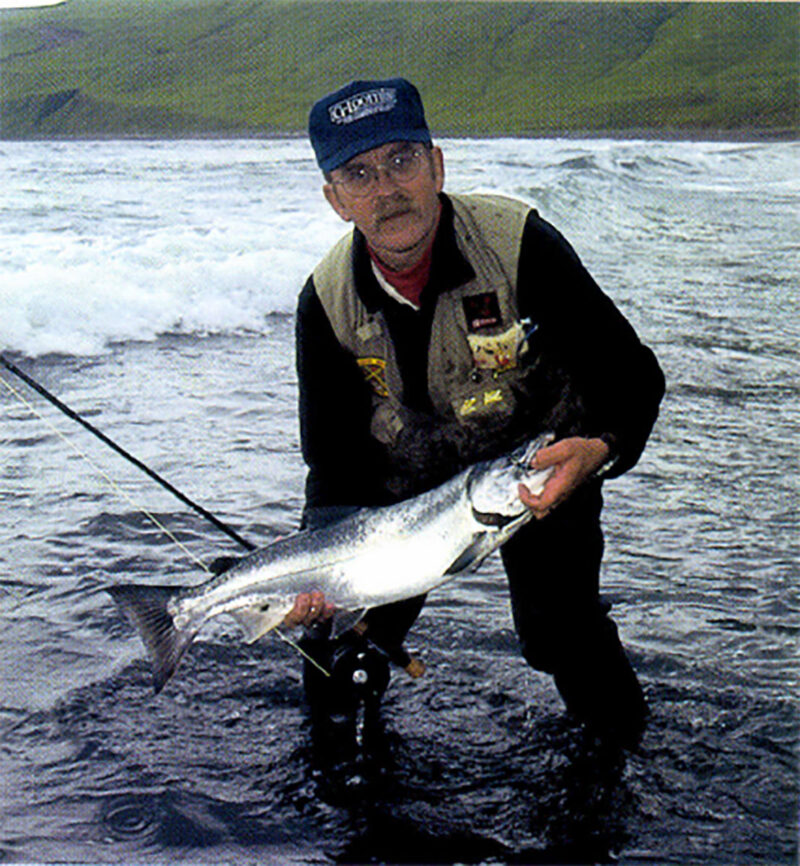

The author struggles with a big silver salmon that minutes earlier had been hotly pursued by sea lions. At Volcano Bay, fly fishermen not only have to put up with hungry sea lions, but a surf that can tumble you head over heels.

About 800 air-miles southwest of Anchorage, the crashing surf of the Northern Pacific tears at the black sand beaches and hills of the Alaska Peninsula, day and night, night and day. The wind that never stops roars through a lush, waist-deep mixture of grass and herbs that cloak the dark sand hills. If you listen closely, the sand of beaches and dunes whistle. Small round pebbles roll and rattle against each other ceaselessly in the surf. With silvery moonlight filtering through white tent canvas, it’s easy to mistake the sound of the restless pebbles for ghost armies chambering and re-chambering tens of thousands of rounds, the wind and whistling sand for squadrons of fighter aircraft, the P-40 “Aleutian Tigers,” that are forever just around the craggy point that juts up out of the ocean. Or to mistake the phantom “Armies of the Mists” for pebbles and ghost P-40s for little more than the howling wind and singing sand. Because do not doubt it, my friend, here on this forsaken crust of ice and raven-black cinder mountains, there are phantoms in the air.

With green-black surf crashing around my waist and twenty knots of wind lacerating my face, threatening to topple me backward with every wave, I feel the tip of my rod load itself behind my head as the back cast unfurls with a quick, hard flick of my wrist that would make fly-casting instructors winch in agony, I reverse the line’s direction and somehow cause the leader to hurtle seaward past my head in a tight Ioop. The fly, a weighted concoction of silver and blue tinsel and chartreuse buck-tail, settles into a trough about four waves out under the watchful gaze of two prowling bull sea lions, their heads resembling bewhiskered conning towers.

“One thousand, one; one thousand, two.” The weighted tip line gets a sharp twitch, then another, smaller one. Only my fingertips sense the slight tug on the other end, the hint of a wallow, but then my rod, reel and brain all scramble to life like a bunch of Yanks that’ve just spotted Zeros on the horizon. There is a momentary flash of reflected sunlight off flickering scales as the big silver salmon shakes itself two feet above the water, then heads for the open sea. The sea lions have disappeared

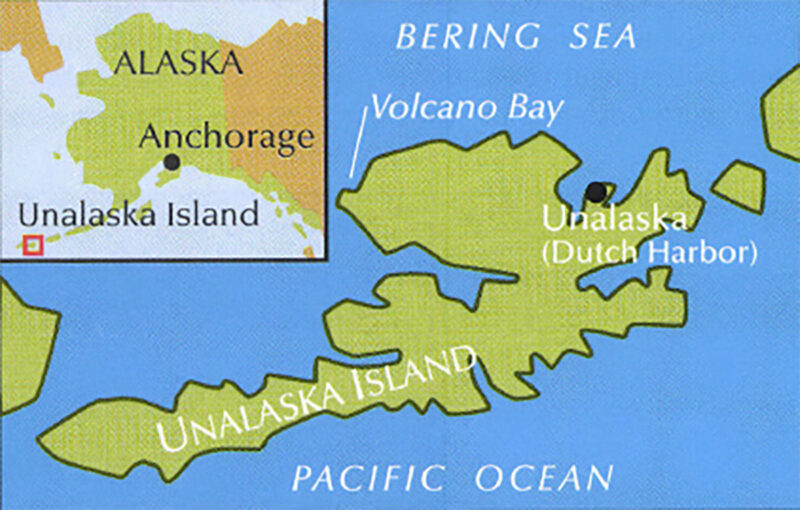

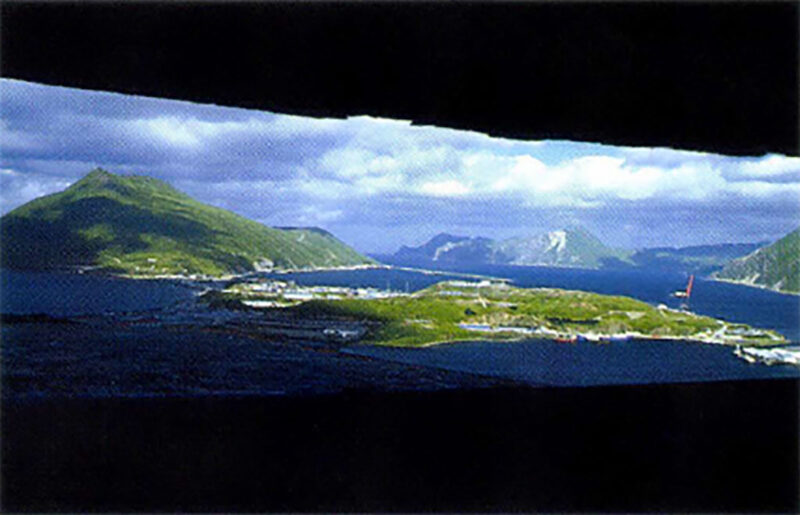

The Volcano Bay camp is nestled among lofty, emerald green mountains on the northwest corner of Unalaska, one of hundreds of sparsely populated islands that make up Alaska’s Aleutian chain.

My reel changes its pitch almost imperceptibly as the tail-end of the flyline zips out through the guides and the lime-green backing begins to unwind. I glance down at the reel and the panicked thought strikes me that maybe I forgot to put on a full complement of backing. I do remember being short on one reel or the other, but was it this one? Already, the first traces of silver show through the wound backing. I clamp my palm down hard on the whirling spool, trusting the rod and line to absorb the shock. My faithful old Loomis 8-weight 4-piece turns itself into a graceful upside-down “U.” The fish slows. I try to remember when I tied the nail knot linking my line to the backing, if I followed the instructions, and if I was sober at the time. Probably not.

Finally, after an eternal fraction of a second, it all comes together. With less than a yard of backing still attached to the reel, the salmon hangs a hard left, then torpedoes back in my direction.

Map of area.

Lifting my rod high above my head, I reel in furiously and manage to keep my line taut until all of the backing is recovered, and I even have three or four yards of line back aboard I now get a glimpse of the big silver, probably a fifteen-pounder, as it heads for the mouth of the freshwater creek near where I am standing. Not wanting to risk having to fight it in the running water or letting it wrap my line under a piece of driftwood, I turn it steadily back with pressure from the rod tip. I can feel the fish, exhausted but still strong and capable of a burst of energy, slowly yielding to my attempt at control. I don’t kid myself. This is a fish just in from the deep ocean that has not yet exhausted any of itself fighting upstream. It is out just past the first line of surf now and simply hanging in place.

Suddenly my reel screams again and I feel the pain of a barked knuckle as the salmon lunges away from me along the beach in a sudden burst of energy. I see the reason for its renewed panic as one of the sea lions ups periscope just a few feet behind it and I see a swirl made by the other as it goes after MY fish! I yell and kick the water with both feet to scare away the sea lions just as a five-foot wave crashes into my chest and over my head. I go down backward into the inky black surf, and it’s all I can do to keep from being tumbled head over heels. Only my hands gripping the rod stay above water or, at least I think they do. I come up gasping for air, spitting black sand and cursing seal-safe tuna nets. I never do find my new cap. The sea lions abandon their pursuit of my salmon. Well, did YOU ever try to chase down and eat a live 15-pound salmon while laughing? Apparently neither had these 500-pound blubber-bearing rodents.

My waders sloshing with a mixture of cold seawater and black sand, and all of me flash-frozen like so many fish sticks, I waddle to my feet and finish landing my salmon.

As I drag it up on the beach just out of reach of the surf, the hook falls out of its jaw and snags my waders. I fall face down on the fish. Talk about luck.

Only with the fish safely ashore do I realize how cold I am and that our little clutch of six tents is nearly a quarter-mile distance. For me, today, the cold ocean will be no problem other than causing a little discomfort. I have warm, dry clothes and hot coffee waiting for me in the cook tent, but for many U.S. and Japanese flyers who were shot down or had to ditch in these same seas during World War ll, the frigid Bering Sea spelled almost instant death.

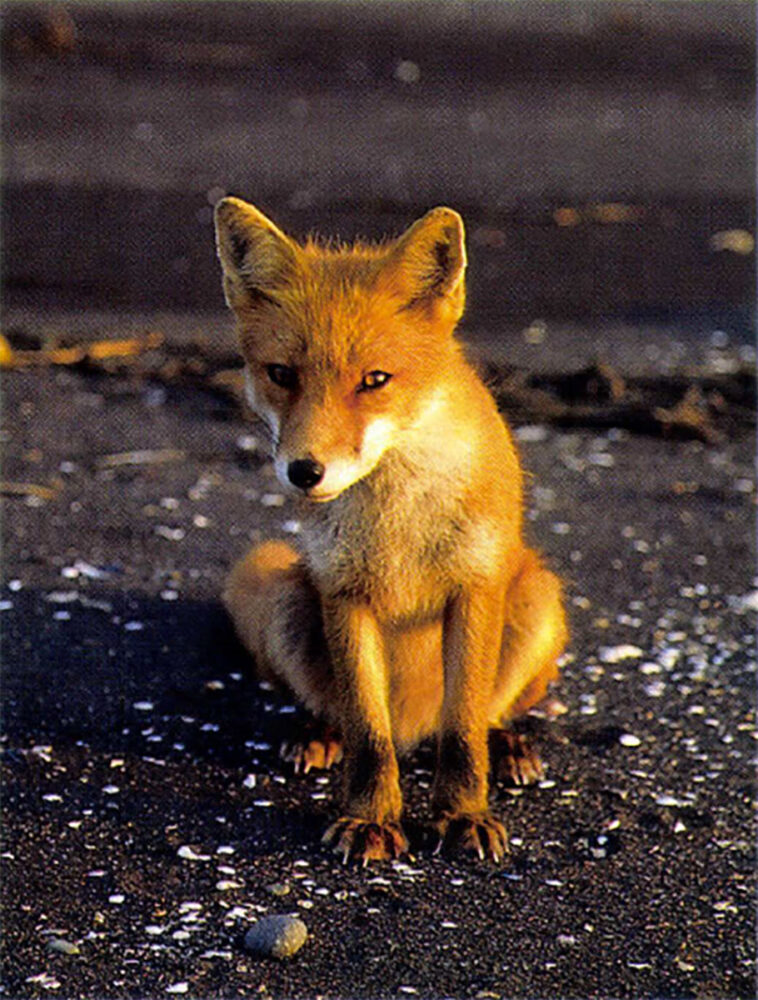

As sly as he looks, this red fox would patrol the ocean shore, begging for handouts from the anglers.

As a major deepwater port that is ice-free year-round, and with incredibly rich fishing waters nearby, this portion of the Aleutian Island chain was highly prized for conquest by World War Il Japan. The Japanese prime minister believed that occupation of even such a small part of America, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, would hurt the United States psychologically and almost divert American sea power from the Pacific Theater. The commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, however, had lived and studied in the US before the war and he knew the Americans better than his prime minister. Commander Isoroku Yamamoto argued against messing with what he referred to as “the sleeping giant.” He later wrote that he told the prime minister, “If you insist on my going ahead, I can promise to give them hell for a year or a year and a half, but I can guarantee nothing as to what will happen after that.” On June 3 and 4, 1942, the Japanese Imperial Air Force bombed Dutch Harbor, about twenty-five minutes by air from Volcano Bay. Forty-three people were killed on the ground and many more wounded. Three days later, on June 6, Japanese forces went ashore and occupied the Island of Kiska. At about the same time, they also occupied Attu, the westernmost peopled island of the Aleutians. It would take more than a year for American and Canadian Forces to dislodge the invaders, but Commander Yamamoto’s prophetic words would prove all too true for the Rising Sun. Today, many of the artifacts of war are preserved as part of the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area.

In the madness that was WWII, the native people suffered at the hands of both Japanese and Allied troops. The Japanese took prisoners of war and abused them brutally; the Allies moved the native people involuntarily to internment camps in faraway southeastern Alaska. Many died on both sides, but in a brochure written and printed by the U.S. Park Service, there are the typical lengthy descriptions of how badly our side acted toward the indigenous peoples, far less mention of Japanese atrocities.

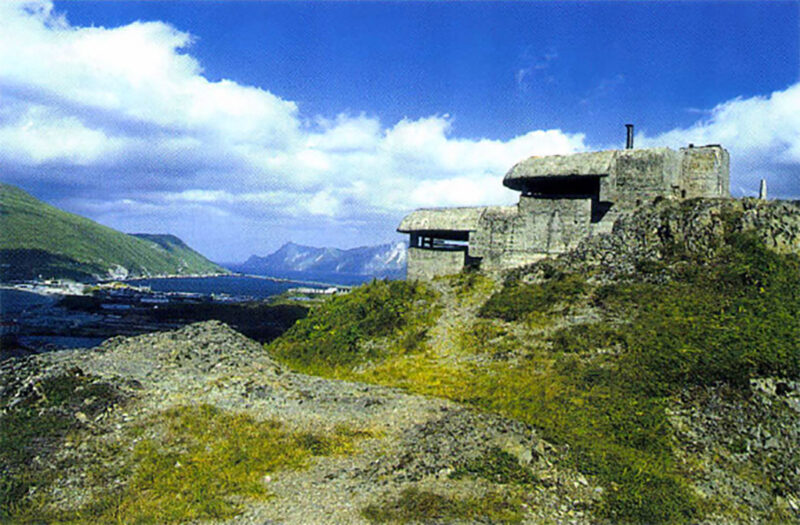

From a window of the bright blue Grumman Goose flying us out to Volcano Bay from Dutch Harbor on a rare, beautiful sunny day, I can see on nearly every hilltop the concrete gun emplacements and pill boxes and the dozens of GI Quonset huts, their red rusty caterpillar shapes contrasting sharply with the dark green mantle of grasses and thickets of bear berries now threatening to swallow them up. Pilot Brent Kennedy of PenAir, which owns and still operates several of the classic old aircraft swoops low for us to have a look. My guess is that he was still building model airplanes during Vietnam, much less World War II, but I also sense that he feels a deep respect for the people who, on the emerald green hillsides gliding beneath us, stood ready to meet both elements and the enemy.

A bald eagle glares into the camera, reluctant to fly off and leave behind his meal of poached salmon.

As the venerable amphibian, built in 1945, glides to a perfect touchdown on a little freshwater lake behind the camp, I spot Greg Hawthorne, our host, guide, cook and the owner of Volcano Bay Adventures, awaiting our arrival with a small aluminum boat for the short transfer of our luggage and tackle downstream to the camp. The Goose actually lowers its wheels and rolls to a stop on the muddy bottom, its tires just barely hidden beneath the water. My fellow passengers and I slither out of the door on our bellies and into thigh-deep water. Fortunately, we had been advised to don our waders before leaving the airport at Dutch Harbor.

A short time later, we have each had an injection of Greg’s sludge-like Alaskan bush coffee, uncased our rods and are headed down the trail to a beach that resembles nothing so much as great piles of gritty black iron filings. The little creek runs out of the lake and down a short drop, then doglegs right behind a long, low barrier dune before finally breaking through the dune and into the surf. Greg has us pause for just a second to explain the finer points of casting for Alaskan salmon, but his demonstration is cut short when his first cast into the stream is intercepted by a silver salmon that seems intent on giving us a demonstration of its own. Although Greg complains that this year’s silvers are running smaller and scarcer than last season’s, it doesn’t take long for everyone to hook up with salmon after a cast or two into the surf. Most of our first fish run only eight or ten pounds apiece, but given that these are strong salmon fresh in from the feeding grounds, their relatively smaller size probably turns out to be a line-saver. By the next day, when the fifteen-pounders began showing up, we have practiced enough on the “little” guys that few of us lose fish.

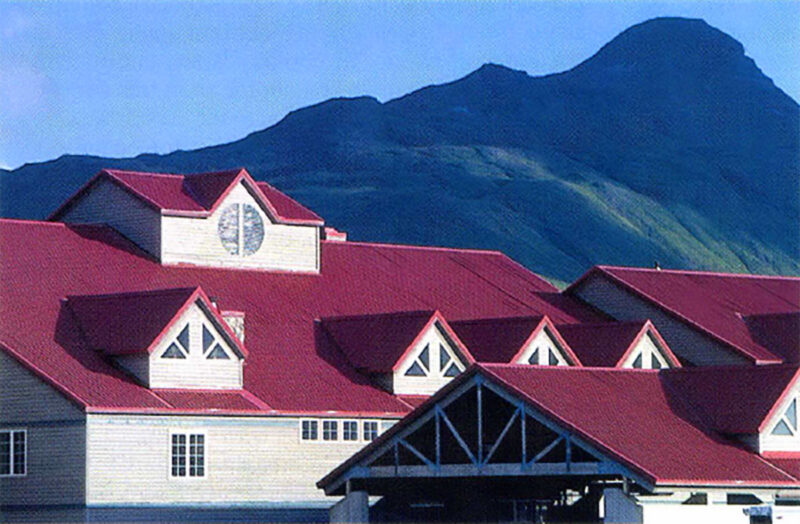

The Grand Aleutian Hotel is a luxurious oasis in the midst of a harsh land.

The next two days are beautiful, with deep blue skies, only a few puffy white clouds and plenty of fish! We even find ourselves getting used to the constant and strong wind well, almost. But by lunchtime on our third day, the weather turns native, the kind of weather you don’t see advertised in Chamber of Commerce brochures. Casting a flyline becomes impossible in the renewed and gusty winds, and a misty fog settles in that seems to soak everything with microscopic droplets of water. Even modern fabrics that aren’t supposed to ever feel wet feel wet. As the wind, which seems almost humanly mad at us for invading its country, tears at the canvas, we quickly come to appreciate that Gary has draped pieces of heavy fish netting over the tents.

By the next morning, we are all more than ready for the sound of the Goose coming in to pick us up, but the wind is still gusting hard and erratically and there’s a ceiling of just about nothing. One or two of us venture half-heartedly to the beach with rods, but the wind, fog and rain make fishing miserable and the salmon appear to have retreated.

Attired in hipboots, anglers await their chance to board a Grumman Goose for the flight from Volcano Bay to Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island.

For more than 60,000 American and Canadian soldiers who defended these islands, this is how it must have been for days and weeks on end. Cold, cut off from news of home, wet, miserable. And yes, for the Japanese soldiers as well. By mid-August of 1943, the Japanese have been chased off both Kiska and Attu. More than 500 Allied troops and 2,500 Japanese soldiers died in the effort. Many of the Japanese soldiers took their own lives rather than dishonor themselves by surrendering.

Dozens of American gun emplacements overlook Dutch Harbor.

Just when we have given up on the Goose, at least for today, we hear the drone of its two engines. Our group of fishermen quickly exchange places with our fresh and eager replacements, our gear and fish are loaded aboard and we are quickly airborne. The Goose circles once, then climbs up high over the ocean and points its stubby nose toward Dutch Harbor.

Through the fogged-up window, I can almost see them down there, those “Soldiers of the Mist.” Do I just imagine the glint of silver off a concealed battery of anti-aircraft guns still at the ready? Or just the flicker of an eagle’s wing glistening wet?

After the solitude of Volcano Bay, the little village of Dutch Harbor with its hotel, two small supermarkets and satellite television, seems crowded even though late summer is the “down” season for a sea food industry that is large, but thankfully, devoted almost entirely to crabs and non-sport fish such as pollack used in imitation crab legs.

Japanese forces occupied two islands in the Aleutians for nearly a year and bombed Unalaska twice, facts that the US government tried to keep under wraps.

After dinner, I take a walk along the waterfront of Dutch Harbor. Dozens, probably hundreds, of concrete pillboxes are spaced parallel to the shoreline. Some workers in bright orange coveralls are draping long fishing nets over them, others are filled with trash and covered with spray-painted graffiti. I see three or four that have slid off into the surf after the beach eroded away beneath them. One lies completely on its top like some kind of overturned concrete turtle.

I voice a little prayer to the Old Gods of these islands that this ruggedly beautiful area will never see war again.

A huge black raven croaks at me hoarsely and glides silently away.

For the first time since I have been in the Aleutians, I suddenly notice that the wind is still. And I can no longer hear the clinking pebbles.

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now