A reader recently wrote and asked:

Hello Mr. Spomer,

Would like your expert advice if you have time. On my family farm two sides of farm now border extremely busy highways. I am extremely nervous about firing a traditional centerfire cartridge like a .270 or .30-06 due to distances these cartridges can cover if I miss my target. I am looking into switching to straight-walled cartridge rifle. Do you have any recommendations on which calibers would be best? The game on the farm are whitetail and hogs. Most shots will be taken at less than 100 yards. Thank you for your time.

Michael

Michael, you are a cautious and wise man to consider this. Accidental strikes from hunting bullets are extremely rare, but they do happen. Your cartridge choice will depend on bullet selection, shooting angles, ricochets, and, of course, lethality for the game you hunt. To begin our search for the safest hunting cartridges, let’s see just how far some cartridges can push their projectiles.

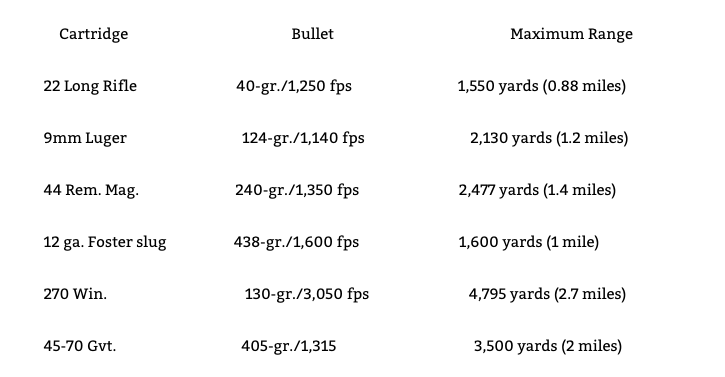

HOW FAR CAN SAFEST HUNTING CARTRIDGES SHOOT?

These approximate distances are reached by aiming upward at about 30 degrees. They vary slightly depending on bullet B.C. and velocity, but they give us a good idea of maximum range.

Judged by maximum range, no cartridge powerful enough to cleanly kill deer is going to be “safe” inside of 200 yards, or even 1,000 yards. Even a flintlock can throw a lead ball 1,000 yards. Fortunately, deer hunters don’t usually aim 30 degrees above the level, and that raises an essential point for our consideration: realistic hunting scenarios.

REAL HUNTING CONDITIONS SHOULD DETERMINE SAFEST HUNTING CARTRIDGES

Most hunters fire “on the level” (from prone, sitting, kneeling, or standing positions on the ground) or slightly downhill (from elevated stands.) This suggests bullets will hit the ground, brush, or trees long before reaching the kind of extended distances many of us fear.

A standing hunter will hold his barrel about 60 inches above the ground. From that position and from a level barrel fired over dead-level ground, a 130-grain bullet from a .270 Winchester would impact the ground about 600 yards out. A 405-grain slug from a .45-70 would hit at about 260 yards. However, should a bullet be fired at an animal on a hilltop or ridge, range increases significantly. This is why we have a universal proscription against shooting at anything that is skylined. Even a “short range” projectile can be deadly when it’s launched over a rise toward who knows what.

In any given caliber, the shorter, lighter bullets will plow through less brush and carry less energy down range than the heavier bullets. Softer, more frangible bullets will ricochet the least.

We’ll assume for the rest of this discussion that you, gentle reader, will perform responsibly. But, just to be sure we’re on the same page here: NEVER, EVER FIRE AT ANYTHING WITH A CLEAR SKY BEHIND IT. Any and every flying projectile can be deadly dangerous if launched over a skyline. You don’t know what lies beyond. Only shoot when you can see the ground or thick brush/woods beyond your target.

By the way, this potential for any adequate hunting cartridge to throw a bullet far suggests why many state fish and game agencies mandate the use of relatively low-velocity cartridges, what they consider “short range weapons.” (I don’t like calling hunting guns weapons, but that’s another issue.) Other “short range” firearms typically include slug shotguns, muzzleloaders with full-bore-diameter bullets, and straight-walled handgun cartridges like the .44 Rem. Mag. Any bullet that falls to the ground inside of 300 yards has got to be safer than any zipping clear out to 600 yards, right?

Well, not necessarily . . .

DON’T SKIP THE SKIP IN SAFEST HUNTING CARTRIDGES

In the real world, whitetails and feral hogs are not 60 inches tall. A standing hunter would be aiming his barrel down toward a vital zone less than three feet above the ground, so maximum range would be appreciably less than the above values even if the bullet missed high. When hunters fire downward from elevated blinds, maximum bullet travel before impact with the ground is drastically reduced. Ricochet, however, rears its ugly head.

Ricochet happens when a projectile impacts anything hard (even water) at an angle and skips off. The shallower the angle, the more likely the skip. The heavier and tougher the projectile, the greater the skip and distance traveled after the skip. As a general rule, the heavier and tougher a bullet, the more likely it is to ricochet, too. Lighter, more frangible bullets, are less likely to ricochet a significant distance. Nevertheless, ricochet potential raises serious questions about bullets and “short range weapons.”

Even in wilderness like this you should never shoot at an animal with clear sky behind it—regardless how “short range” your rifle.

A few years ago some ricochet studies were conducted. They indicated traditional “short range weapons” (I believe they were 12-gauge slugs) were sending ricocheting slugs thither and yon and much farther than lighter bullets from many long-range, high-velocity centerfire rifle cartridges. The heavier, slower slugs deformed less on impact and retained more energy for ricochet travel. The lighter, faster bullets were more likely to deform or break apart, reducing distances travel after ricochet.

If you’re familiar with straight-walled rifle cartridges increasingly being allowed in “short range weapons” hunting districts, you’re already questioning the wisdom of this. Straight-walled cartridges like the .45-70 Govt., .375 Win., .44 Mag., .405 Win., and the like throw heavy slugs at low velocities. On paper they have much less long-range flight potential, but in real hunting situations they are more likely to ricochet, stay in once massive piece, plow through more vegetation, and do more damage when they hit. What’s the bigger threat? I’ll leave that to each of you to decide.

SAFEST HUNTING CARTRIDGES LESS IMPORTANT THAN SAFEST BULLETS

Carrying this line of reasoning (and physics) further, we come to high-velocity, frangible bullets as potentially the best option for the safest hunting cartridges. Yes, I’m referencing “varmint” bullets here, the kind designed to break apart easily. These might be the safest to fire in the deer woods. Yikes!

This presents us with a classic quandary because frangible varmint bullets are not recommended for big-game hunting. In fact, in many states they are illegal because they sometimes “explode” on tough muscle and bone and fail to reach the vitals. Controlled-expansion bullets were invented to circumvent such undesired performance. Nosler Partitions, Speer Grand Slams, Swift A-Frames and Sciroccos, Hornady Interbonds and GMX, Barnes TSX, Winchester Power Max bonded, Federal Trophy Bonded Bear Claws, and on and on. Dozens of bullets have been engineered to withstand break-up, stay in one piece, and penetrate deeply. And, as an unfortunate side effect, ricochet. So what do we do?

Tough, solid bullets like those on the left are more likely to stay in one piece and ricochet farther than more frangible bullets that break up upon striking anything. All of these were recovered from game.

Over the years I’ve done considerable research by hunting a variety of big-game animals with a wide variety of cartridges and bullets, including varmint cartridges and bullets as light as the .221 Fireball throwing a 50-grain Hornady V-Max (which worked surprisingly well on an 80-pound hog 150 yards away.) Frangible varmint bullets at high velocity are never recommended by “the experts” because they really can “blow up” on major muscle and bone and fail to reach the vitals. However, when slipped behind the front leg into the thoracic cavity—or in the neck toward the spine—fragile varmint bullets at high velocity kill big game quickly and dramatically. I’ve found them to reliably penetrate hide, rib muscles, and rib bones of whitetails, pronghorns, and hogs before breaking up dramatically, sending shards outward to create a shallow but wide pocket of trauma that causes rapid and massive hemorrhaging and quick death.

Does this mean you should use a .22-250 Rem. with a 50-grain V-Max varmint bullet for your deer rifle? Not exactly. It means you should take a hard look at lighter, more frangible bullets in whatever cartridge you’re shooting. Consider using those if you’re concerned about excessive bullet ricochet. The lighter, softer, or more frangible the bullet, the less likely it will ricochet significant distances.

A 75-grain .243 varmint bullet behind the front leg “exploded” in this buck’s heart. It took one leap and fell dead in two seconds.

It doesn’t have to be an “official” varmint bullet. Many of our traditional cup-and-core bullets are made with relatively thin jackets and soft lead cores. These break up fairly easily, or at least deform significantly upon striking anything. That alone reduces recoil by converting an aerodynamically efficient projectile into a spinning, rapidly slowing slag of metal. Or several smaller slags.

Some of the more frangible cup-and-cores you should consider include Federal’s traditional soft point, Winchester’s Power Point, Remington’s Core-Lokt, Hornady’s SST, Speer Hot Core, Sierra GameKing, Nosler Ballistic Tip. These are not all equal. Some have thicker jackets and bases than others. Some of the larger calibers are tougher than the smaller. They’re just worth investigating.

Speer probably didn’t have deer hunting in mind when it created its 100-grain .308 round-nose plinker, but a light bullet like this, even at modest velocity, can handle whitetails without being a long-range flight risk—or ricochet threat.

If legal where you hunt, you can also try genuine varmint bullets and various hollow points. I’ve employed Hornady V-Max and A-Max, as well as Sierra BlitzKing, Nosler Ballistic Tip and Winchester varmint bullets, to absolutely flatten whitetails (broadside, heart-and-lung hits) with .22-250 Rem., .243 Win., 6mm Rem., .25-06 Rem., and 270 Win. rifles. Sierra’s 90-grain hollow point in a .270 Win. is devastating on deer but isn’t going far once it hits brush or the ground. Ditto the 110-grain Hornady V-Max and Nosler 115-grain Custom Competition. In .30-caliber cartridges, look for 110- to 130-grain cup-and-core bullets.

Obviously, handloaders are going to have many more options than folks who shoot factory-loaded cartridges. You just don’t find many light bullet options in traditional, factory-loaded “deer” rounds.

A light, 115-grain bullet in .30-caliber is less of a ricochet threat than a heavier 210-grain, yet it can terminate deer dramatically if properly placed.

Warning! Light, frangible bullets are not something you fling willy-nilly at deer. No north-to-south shots. No trying to plow through a ham or massive front shoulder to reach the vitals. You must be selective and wait for clean, broadside shots behind the leg or neck/spine shots. Precision is essential.

In conclusion, to shoot safely in “short range” areas, keep shots aimed toward the ground—no clear-sky backgrounds—and you should be safe. Minimize ricochet with light, fairly frangible bullets, and choose your shots carefully. Ricochet happens. And that’s why we must consider not just bullet trajectory, but reduced-ricochet cartridges and bullets when hunting in settled country.

For more from Ron Spomer, check out his website, ronspomeroutdoors.com, and be sure to subscribe to Sporting Classics for his rifles column and features.