The safari began as an East African phenomenon. The word itself has an Arabic origin – safariya (a journey or expedition) – and from this came the Swahili synonym, safari.

The first safaris were undertaken by Arab traders in the 18th century when their caravans crisscrossed the African continent. These huge caravans carried such prized commodities as elephant ivory, rhino horn and, of course, slaves destined for Arabian, East Indian and Chinese markets.

The grisly slave-trading era ended when the British cut a deal with the Sultan of Zanzibar in 1890 to establish a protectorate and better manage the land-grabbing that was rampant in the region.

In 1896 the British took control of the protectorate and laid the groundwork for a different kind of safari. That led to a new era in which the great hunting legends would emerge and a new kind of safari would come of age. Through the expeditions of European hunters such as Frederic Courteney Selous, William Cornwallis Harris and A. Blayeny Percival the first seeds of conservation ethic were sown.

Stand Steady, 2009 by John Seerey-Lester.

The safari became the ultimate adventure and was romanticized by a multitude of writers, among them Rudyard Kipling and years later, Ernest Hemingway. But it was perhaps the writing of famous big game hunters such as Selous in his 1881 book, A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, which inspired many British and European sportsmen to discover Africa.

The safari as we know it today began just before the turn of the 19th century, but it wasn’t until 1904 that it became an organized and commercial enterprise.

Messers. Newland & Tarlton (N&T) and the Boma Outfitting Company were the most prominent organizers of early safaris. Their clients would travel by ship to the ancient coastal city of Mombasa, then journey by train to the then-frontier town of Nairobi, British East Africa. After getting organized at the newly opened Norfolk Hotel and picking up some last-minute items from local merchants, they headed out into the bush on foot, horse and oxen wagon to great fanfare. British and European sportsmen soon realized that Africa was a finite resource and arrived in droves to take advantage of hunting this pristine land.

Depending on the client’s budget, it was recommended that the average safari would need a minimum of 30 pagazi (porters) per sportsman, one neapara (headman), one m’pishi (cook), one tent boy, one gunbearer, two askaris (soldiers) and, of course, a professional white hunter. If the hunters were on horseback, then they would also need a syce (horse groom).

In 1909 the cost of a safari in British or German East Africa ranged from $300 to $500 per month, excluding the white hunter’s fee. Food for the safari was selected by the client and would be brought in boxes, usually from the Army and Navy stores in London. Ammunition was another added expense and a hunting license would cost $250.

The British imposed a ten percent customs charge on all items brought into the protectorate. Altogether, these goods and services quickly added up to an expensive adventure, one that only the wealthy could afford.

Sportsmen were encouraged to use one of the established safari companies, such as N&T, but some of the more adventurous hunters organized their own. There were a limited number of merchants in Nairobi at the time, but a sportsman could get his khaki shooting clothes made to measure in a couple of days. The more essential items for the expedition had to be brought in at great expense from England, Europe or America.

Sportsmen were advised to bring two pair of hobnail boots and extra nails for long safaris of several months or more. Puttees, or leggings, were recommended as were lightweight mosquito boots to wear at night. Saddles and bridles had to brought in, along with most of the camping equipment. At the time, Edgingtons of Duke Street in London was regarded as the supplier of the finest tropical green tents made from Egyptian cotton. The most popular size was 9- x 8- x 7 ½-foot. Safari-goers had to ship camp tables, canvas chairs and washbasins, their brown Jaeger blankets, hair mattresses, cots and pillows, and the ubiquitous hotwater bottles for chilly evenings. For the very discerning sportsman, it was essential to have caviar and the finest champagne along with silverware, crystal and china.

All safari supplies had to be carried by the pagazi (a limit of 60 pounds per man), so careful organization and packing were necessary. The massive caravans moved slowly over the Dark Continent’s difficult and varied terrain, but that mattered little because the sportsmen soon realized they’d arrived in a land unsurpassed for hunting big game.

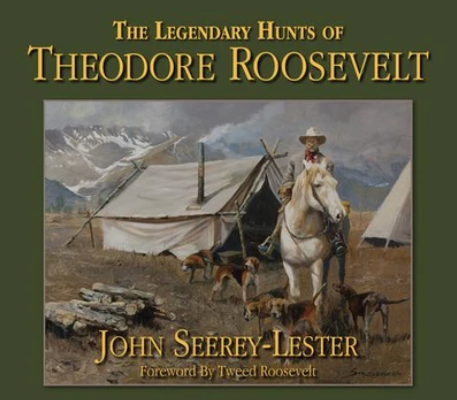

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now