Native Africans who work for safari companies have an apt and often unflattering way of naming sportsmen. Almost never do they call them by their proper American or European names, as these names are as strange, meaningless, and as difficult to pronounce for them as their own names are for the sportsmen.

So when my wife, Eleanor, and I were hunting in Mozambique with two friends, we all got names. Dr. Sib West, a Willows, California, dentist was very lucky. He had a tape recorder with him. The camp boys were impressed and called him Mister Music Box. Fred Huntington, a reloading tool manufacturer who for the purposes of the trip had dieted down from a blubbery 245 pounds to a lean, hard 241 and who was proud of his new figure, was simply called Mafuta, the fat man. My wife, who has always fancied herself the strong, silent type, a sort of a female Gary Cooper, was shocked when she learned that the natives called her Scotia – the little woman who talks all the time.

In spite of my years, I have always thought of myself as a sprightly, shopworn college boy, but the camp lads named me Medala – the old man. I have always considered myself a fair shot, but they soon emended my name to The Old Man Who Can’t Hit a Pala Pala. And in this there lies a story.

The concession, or coutada, run by Mozambique Safarilandia on the Save River in Portuguese East Africa swarms with exotic types of African antelope both great and small, including greater kudu, nyala, waterbuck, impala, reedbuck, bushbuck, wildebeest, eland, steenbok and oribi. There are also sable, the big black antelope with the scimitar-shaped horns, but at first my wife and I had a hard time finding them, and I had a harder time hitting one.

In Mozambique, sable are called pala pala by the natives, the same word used by the Swahili-speaking inhabitants of Tanganyika, a strange circumstance since Swahili is not used in Mozambique. The sable is in size about midway between a mule deer and an elk. Cows and young bulls are brown, but old bulls are jet black, hence the name. From reports I had heard I expected to see bulls with exceptional heads in Mozambique, but if there are big heads in the country, they are not on the Save River. We certainly didn’t run into any. But that is getting ahead of the story.

We picked up a couple of handsome bull nyala very quickly, then knocked off a bushpig, warthog, waterbuck and a buffalo. All the time we had our eyes out for sable. Almost every day we saw their long, pointed tracks, but never the sable themselves. Fred and Sib each brought in a sable early in the trip, but for ten days we didn’t lay eyes on one.

All this piqued us somewhat but did not break our hearts. Eleanor and I had both shot sable previously in Tanganyika. We had taken good bulls in 1959, and when I was on my first African hunt in 1953, I had shot a beauty with horns 44¼ inches around the curve. This, I believe, was the largest taken in Tanganyika that year.

For all his spectacular beauty, the sable is generally not the most difficult of animals to come by, once the hunter is in sable country. Sable run in herds of up to 40 animals. Since both bulls and cows have long, sharp horns and know how to use them, they have no need to be as wary as more defenseless animals. Even a lion shows great respect for the horns of the sable, and more than one hunter who has approached too close to a wounded sable has been impaled on those needle-sharp horns.

We had been hunting about ten days in what was generally considered good sable country before we ever saw one. Then one morning when we were cruising around in a four-wheel drive hunting car with Harry Manners, our white hunter, we saw our first herd. It was almost a mile away in the brush across an open, dusty plain. Our binoculars didn’t show us much, but we could see black bulls as well as brown cows. We decided to investigate.

We left the hunting car about 400 yards from where we had seen the sable. Because Harry insisted, I took my .375. Eleanor tagged along with her 7×57. Harry led us upwind toward the herd. Presently, we saw a movement ahead of us in the brush. It was a cow. Then we saw two or three more cows and a young bull. We had the wind on the herd, so we worked to our left to see if we could find a shootable bull. We did, but he was behind a cow and all I could see was his head and his hindquarters.

“I think he will go 40,” I told Harry.

“I doubt it,” he said. “The biggest sable ever shot around here went 40 and it was bigger than this one.”

“He’s shootable, though,” I said.

“Very much so,” Harry agreed.

The grass was high there at the edge of the forest and the brush was fairly thick. The bull sable was about 200 yards away. I found myself a good tree, put my left hand over a branch and rested the fore-end of the .375 on it. When I got a clear shot at the bull, I’d let him have it.

But the bull wasn’t cooperating. He and the cow walked together across an opening with the cow’s body still shielding the bull. Then they stopped behind some thick brush. The bull stayed there, but the cow moved on. All I could see was the bull’s head.

Watching through my scope, I waited, and waited and waited. Finally, I decided to hold where the bull’s shoulder should be and see if I couldn’t put a 300-grain Silvertip bullet through the brush.

When the .375 bellowed, I saw small limbs, twigs and leaves fly, but the whole herd of sable took off, running through the forest to our left.

“Think he’s hit, Harry?” I asked.

“I doubt it,” Harry answered.

We followed for about 300 yards and presently Harry, who was ahead, held up his hand. “There’s the bull,” he whispered.

I edged forward. The bull was looking in our direction, facing us, but again he was concealed by brush except for his head. I estimated where the center of his chest should be and took a rest on a branch. Again the .375 bellowed and leaves and twigs rained down.

The bull whirled and ran off. The next time we saw him he was over 400 yards away, galloping along with the herd as good as new. We went back and examined the ground where he had been standing. No blood. Apparently two clean misses. I am sure that was the best bull we saw in Mozambique. He might not have gone 40, but he didn’t miss it by far.

Until then I had knocked over everything I had shot at, almost always with one shot, and our two gunbearers, Joe and Julius, had even done a little bragging about their old man’s shooting. But as we rode back to the Zinave camp by the river, the atmosphere was thick with gloom.

A couple of days later I took another pop at a sable, a lone bull this time. But I was jinxed. I could see the sable’s body, though there was a fair amount of brush between me and the bull. He was about 200 yards away and I had a good solid position, but when I fired, he galloped off.

I couldn’t believe my eyes, but as I stood there staring I suddenly noticed, about 100 yards away, the limb of a tree slowly bending towards the ground. I walked over to it and found that I had just about shot the limb in two. I felt a little better. I didn’t have the sable, but at least I had an alibi. So that’s how I became known as The Old Man Who Can’t Hit a Pala Pala.

On the Save, it is the custom not to hunt on Sunday – or at least not very hard. It is the day off for the white hunters. Harry had his wife and little boy with him, and Wally Johnson’s wife was there in camp at the time mourning the death of their pet dog. It had been pulled into the river and devoured by an enormous crocodile.

On that particular Sunday, Eleanor and I slept late. We saw Fred and Sib at breakfast, then went back to our hut to read, write some letters and make some notes. Presently, I heard the roar of a hunting car. Fred, Wally and Sib were off to do a little photography and to pop off an impala for camp meat. I had borrowed a book from Harry, so I settled down to read and maybe take a snooze. I was pounding my ear an hour later when Harry knocked at our door.

“Come on,” he said. “Grab your rifles, you two. Wally has located a fine herd of sable on this side of the river.”

We found them easily. There were about 50 of them and they were strung out over a wide, grassy plain near a waterhole. Among them were several shootable bulls, but the glasses told us that nothing would be very close to 40 inches.

“Well,” said Harry, “the best bull looks to me to be the second from the right, but the one farthest to the left is also good. Who’s going to take one?”

“It’s mamma’s turn,” I said. “I’ve booted two chances, and I think she’s just about the gal to break our sable jinx.

“All right, Eleanor,” Harry said. “You’d better take Jack’s .375 and we’ll get going.”

“I loathe .375s with a purple passion,” Eleanor said. “I shot one once and I couldn’t lift my arm for a week.”

“She’d better take her 7mm, I said. “She’ll hit it in the right place, but with the .375 she might not.”

Harry shrugged. “Well, have it your way,” he said.

It was an easy stalk. The sable were real back-country animals and they had hardly bothered to look at the hunting car. Harry and Eleanor walked perhaps 150 yards and climbed an anthill. As I sat in the car watching, I could see her take a good prone position and put her 7mm to her shoulder. Harry was watching the sable through his binoculars. I’d guess they were about 250 yards from where Eleanor lay.

I put my own glass on the bull. I heard the sharp crack of the 7mm. The bull sagged at the front quarters, then began a desperate, blundering run. He traveled in a little circle not over 50 yards in circumference. Then he plunged down into the grass.

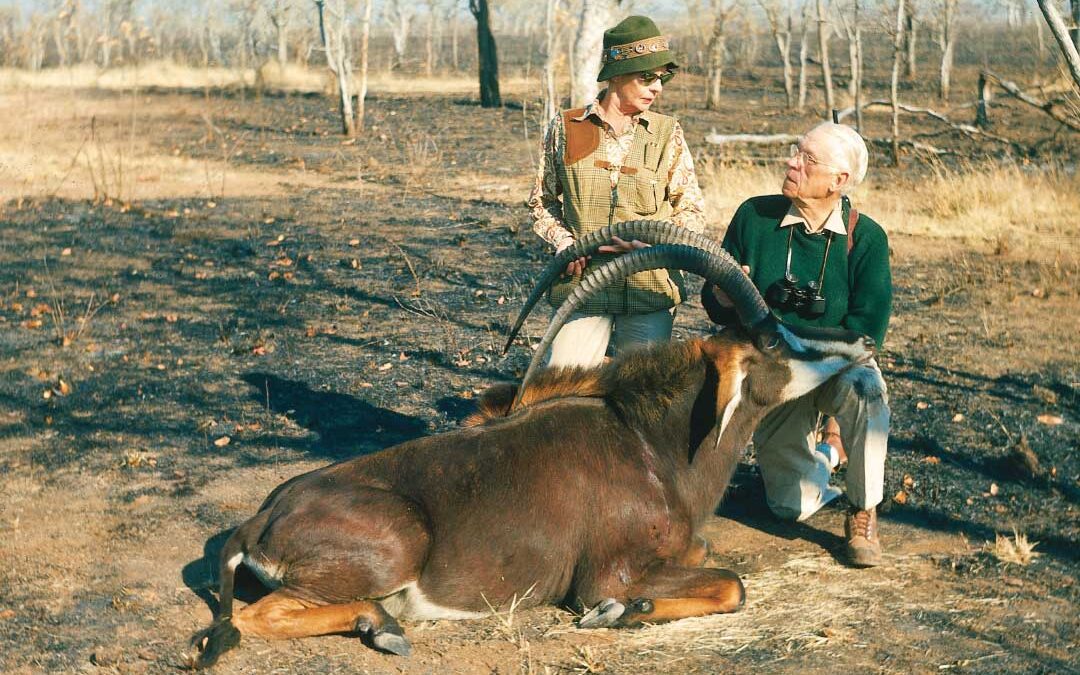

I joined Harry and Eleanor by the sable, where Harry was measuring the head.

“Well,” he said. “Old One-Shot Eleanor and her little peashooter have both lived up to their reputations.”

Eleanor grinned at me. “The first step in getting a sable is to hit it!” she said. “It’s all very simple to those who know.”

The head was nice-looking but measured only 36 inches, about par for a trophy sable on the Save, but small compared with the 41 to 44¼-inch sables we had shot in Tanganyika and also small compared with the sable we were later to take in Angola. The kudu on the Save have magnificent horns and are as big as horses, but the sable simply don’t grow large.

We saw our next sable under conditions that could happen only in Mozambique. We had left camp before sunup that morning, as we had a long way to go. It was midwinter there far below the equator and we were chilly even in light down jackets. When we got to the river to be ferried over to the hunting car in a dugout canoe, steam was rising in the cold air from the smooth surface.

We drove off with the fantastic shapes of baobab trees outlined black against the pink flare of the sunrise. Below us the river was rose and silver. Waterbucks stood tall and stately along the trail and hordes of the little Angola impalas scurried across in front of us.

The sun was well up, but it was still early when we drove through a long valley filled with high grass and tall fever trees with feathery tops and green trunks. The valley was spotted with waterbucks, zebras and elands.

Then the track left the valley and started winding up to a high, dry plateau. We were almost on top when, to our left, four big greater kudu bulls stared at us for a moment, then started trotting up the hill. At the same time, a big bull sable galloped out from behind a bush and headed for the crest. He frightened an excellent bull nyala, which also took off.

There, in view at the same time, were three of the great African antelope trophies – trophies for which many a man has hunted hard for weeks. It would have been possible for a very good, very fast shot to have a kudu, sable and nyala from that one spot. Harry stopped the car so we could glass the kudu. They were jittering around, still in sight.

“I still don’t believe it!” Eleanor said. “Kudu, sable and nyala all at once!”

“Nothing over fifty,” Harry said, watching the kudu.

“I’ve seen plenty of places where a man would hunt hard for a week and be lucky if he saw one bull kudu that went fifty,” I told Harry.

“Not here,” he said. “Well, shall we go on and see what happened to our sable?”

We pulled up on top and saw that the dusty track ran through a grove of tall, beautiful trees. The sable had followed the road and we could see his fresh tracks in the dust.

Because we had frightened him with the car, we left it by the road and took off on foot. We saw the sable again, but just once. He had gone on through the woods and was standing about a quarter of a mile away out into the midst of an open plain, looking back in our direction. He saw us as soon as we saw him and ran off at a gallop. We watched him until he disappeared into the bush a mile away.

“Well, goodbye sable,” Harry said. “See how wild he was? There’s a lot of game up here on the plateau, but also a lot of poaching.”

We saw a big herd of sable that day on an open plain about a mile away. But they were as wild as the lone bull. They dived into the brush the instant we drove in sight, and all we saw of them after that was the cloud of dust they raised as they raced to safety.

A day or so later we had climbed a little hill so we could look around when Joe, the gunbearer, hissed, “Pala pala.” Below us and not over 100 yards away was a herd of sable, but there was not a shootable head in the bunch.

Our break came unexpectedly. We had crossed the river one cold morning and were headed back to the plateau where we had seen the big, spooky herd. An exceptional bull waterbuck, which we watched with binoculars for a few minutes, delayed us.

Our break came unexpectedly. We had crossed the river one cold morning and were headed back to the plateau where we had seen the big, spooky herd. An exceptional bull waterbuck, which we watched with binoculars for a few minutes, delayed us.

We were about to drive off when Joe jumped as if he had sat on a pin. “Pala pala!” he whispered.

I followed his pointing finger and, through a long avenue in the scrubby trees, I saw a sable walk into sight and disappear, then another and another. The glasses showed sable all over the place. “Well,” I said. “I’m not going to louse it up this time.”

“Take the 7mm Magnum,” Eleanor said. “That hell-roaring .375 is jinxed!”

Taking the 7mm Magnum, I crawled out of the car, and with Eleanor and Harry began a long circle that would bring us close to the herd with the wind right.

Half an hour later I was ready to shoot. There were about five sable, two bulls and three cows, in the space between a couple of trees, and for once I had a good clear shot at the largest bull. He was not very far away, probably not 200 yards. Since the grass there was short and sparse, I sat down, got in a tight sling, took a deep breath, released about half of it and started my squeeze. The Model 700 Remington Magnum cracked and I heard the solid thump of what sounded like a hit in the rib cage. All the sable vanished in the brush.

Joe and Julius hurried ahead and instantly found a blood trail. A very confusing circumstance was that the blood we saw was not plentiful and it looked like that from a muscle wound. If ever I had called a shot, it had been that one. The intersection of the cross-wires in the Redfield 4X scope had been exactly behind the foreleg and about halfway down from the backbone when the rifle went off. Since the bullet should strike about four inches high at 200 yards, the shot should have been smack through the lungs.

That herd of sable had come in from the remote back country to be nearer the water of the Save River. They were not used to being hunted and had quickly got over their fright. We caught up with them within three quarters of a mile.

“Hell,” said Harry. “That’s not the sable you shot at!”

Then I saw the young bull that had been with the herd. Apparently the 175-grain bullet had gone through my bull and had wounded the young one, as he had a long, shallow flesh wound across the rump. No wonder the blood looked as though it had come from muscle.

So we retraced our steps and went back to the place where the sable had been. There we found another blood trail, and this time it was the bright, frothy blood of a lung shot. We followed it not more than 100 yards and found the big bull lying under a tree. The bullet had hit just where I had called it. Like Eleanor’s, my sable’s horns went about 36 inches – not big as sables go, but good enough for the Save River country.

That took care of our sable jinx. From that time on we saw sable almost every day. No longer was I The Old Man Who Cannot Hit a Pala Pala. I was just the Old Man.

Originally published in Outdoor Life, July, 1965. Reprinted with permission of Outdoor Life.