At the tail end of that shallow, hopeful musing, a very small bear cub stood up in the middle of that brown fur patch and looked at me from ten yards away.

We parked the truck above the Russian River, the life blood of the Alaska’s famous Kenai River. The summer morning held a soft, quiet demeanor, and my boys, my dad, and I anticipated finding a horde of red salmon stacked in a holding pattern upstream.

Anyone who has fished the Russian knows what it is like to be elbow to elbow with crazed fishermen flailing the water, hoping to walk away with a limit of reds and both ears intact. This was not one of those mornings, though. Walking up the trail that runs along the river’s edge, we could see a few folks up ahead in the water, but the crowds were somewhere else. The morning was quiet and still with a low, cool mist hanging gently over the water. The Russian meandered, gurgling its way to the Kenai River.

The trail running along the river’s edge entered a tangled tunnel of overhanging alders mixed with willow, cottonwood, and spruce. I have never liked this trail simply because of the bear proximity and the diminished visibility. My holstered bear spray was always on my right hip. On this particular morning, with the mist and the quiet and the missing fishermen, and the tunnel of brush, it became a scene from The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, and I was feeling more and more like Ichabod.

I heard branches break off to my left. I was leading, my teenage sons were right behind me, and my dad was bringing up the rear. I stopped; I saw movement, and I knelt down to look through an alder opening about the size of a watermelon. Brown hair, or was it fur? I remember my single thought at that moment: Lord, please let that be a moose.

At the tail end of that shallow, hopeful musing, a very small bear cub stood up in the middle of that brown fur patch and looked at me from ten yards away. My highly energized brain relayed an important, monumental message, and I didn’t waste any time relating to my family the contents of which I could hardly believe. I still held hope that we could gingerly retreat, laugh about our close encounter, be thankful about this and that, and go about our business of finding fish . . . somewhere else. But then the grizzly sow stood up and had my attention. All of it.

When a brown bear roars from ten yards, the world narrows down precisely to the realization that the control I have over my immediate existence is nothing more than a façade on an old lag structure. The boys later said that when I yelled at them to vacate the premises, I had inserted a four-letter word somewhere in the middle of that great, short speech. Personally, I find that hard to believe; they have both been known to exaggerate.

The sow’s head dropped from sight, and it didn’t take her long to find her traction. I have read stories about a bear’s charge breaking brush and uprooting small trees, but to witness the event from a front-row seat as it unfolds is both horrific and awesome. Only Moses could have parted that mass of intertwined alders and willow faster. Maybe.

She looked like a hummer, and her weight was not a hindrance during the acceleration portion of this colossal event. The bear spray was in my hand and was pointed in the direction of the exploding alders. The only, and I mean the only, thought I had was, I am going to push this little red button until she is on top of me.

The last visual I had of that raging, roaring, disturbed sow was at about ten feet. Her mouth was open, and the pink inside was harrowing, stark and lovely. I remember the tongue and the black, loose lips, and then I pushed that marvelous little red button and the world stopped. She came sliding in, and although I could not see her entirely through the fog of the spray, all four legs were planted firmly as if she were sliding into home plate. Dust, brush, and dirt mixed with the spray fog, and then she was gone. Just like that. No more brush breaking. No noise. Nothing. Just the same simple misty-morning quiet that had lingered before.

As soon as I realized that I was not going to be on the front page of the next day’s Anchorage Daily News, I lost what composure I may have had, turned tail, took two quick steps, and hurdled my father, who was upside down in the ferns with his glasses cockeyed across his face. He had a placid, unconcerned look, like he wasn’t really sure what was happening and, frankly, it didn’t much matter to him anyway. Maybe that is the peace that comes with old age, or maybe it’s not.

The teenagers were nowhere in sight. I landed on the other side of Pops and was instigating a full-scale retreat when I retrieved partial sanity and realized that I couldn’t just leave the old fellow lying in the ferns. Once I had him on his feet, we skedaddled.

Finding the boys on an open gravel bar in sight of other fisherman, we stopped to collect what was left of our senses. I asked Dad how he came to rest upside down in the ferns and mud in the middle of this debacle. The thought crossed my mind that he was playing possum, which probably would have been a good strategy given his speed in the 40-yard dash. He showed me the muddy tracks that ran up his chest and over the top of his receded hairline. My youngest teenager looked sheepish; my older teenager stood his ground and clearly explained that those tracks were not his because he simply put his shoulder down and bowled Grandpa over. It is always great to know who has your back.

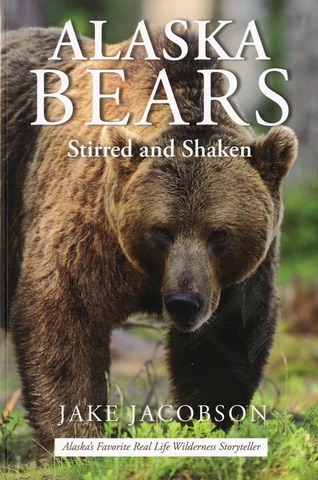

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now