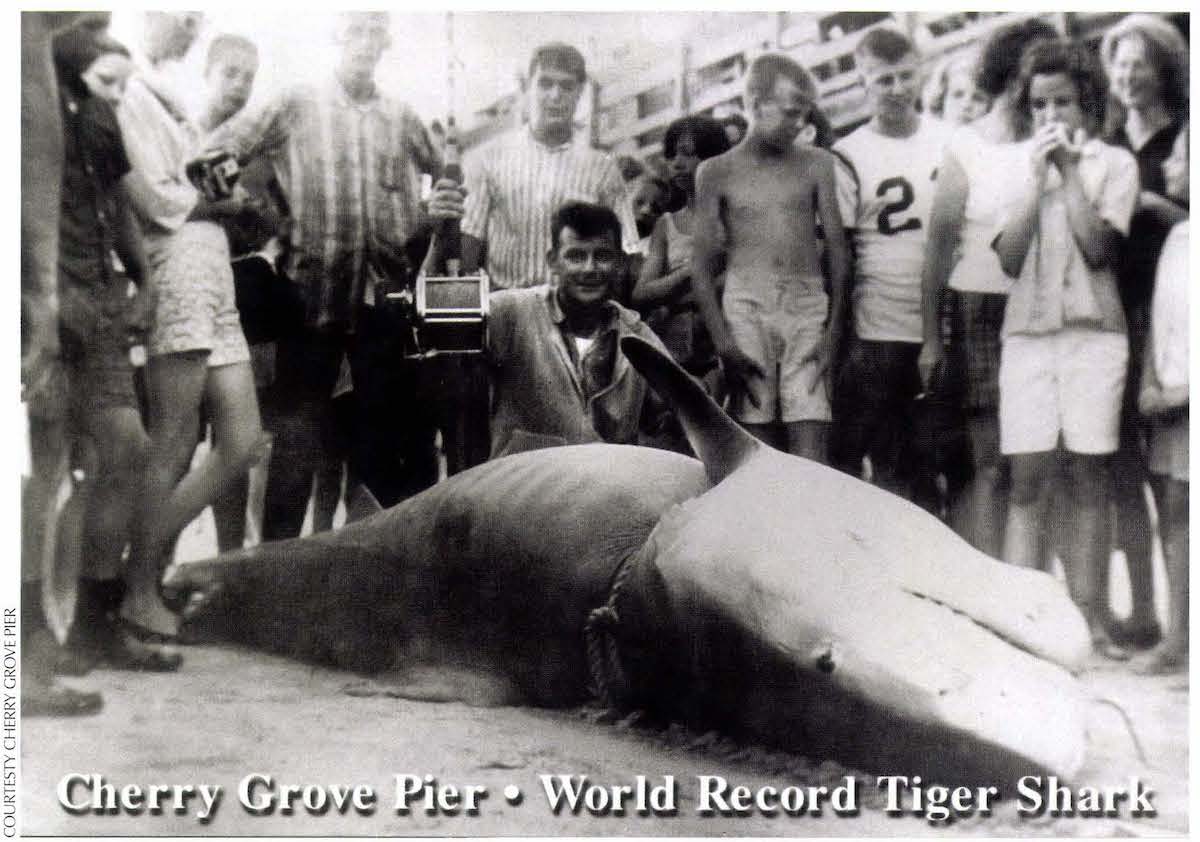

When the shark hit the end of the line, it came up, shook his head just like those mahi did. The dock bowed, creaked, groaned, sagged.

Clink, clink, clink. I was bent over the gunnel of Maggie C, a 26-foot Maine lobster boat rigged for ocean-running. Six weeks, 600 miles we were in the Exumas trying to get home, and I was busting rum bottles over the side. Two, maybe three bushels of them, I disremember in the fine alcoholic haze. I wore my shades to keep the splinters from my eyes. You don’t want a bad eye in the Bahamas – a bad anything else either.

The Exumas are a string of 300-odd islands on the edge of the world, 90 miles from Nassau, 3,000 from Africa, population 700. In the native bars, they sell you the imported mixer but give you the local rum, sweet and dark, served up in half-pint flasks refilled from a barrel in a back room. The local girls await your interest, sweet and dark too.

Such practices would be criminal offenses most places, but the Bahamians place great emphasis on a genteel efficiency rather than the letter of the law. Drop-dead beautiful brown girls, conch, lobster, fish, fruit, feral goats and hogs, occasional cinnamon teal wintering in their salt ponds, nature laid its bounty at their bare feet and a more contented people you would be hard-pressed to find.

“Not to worry, mon, soon come,” is the National Mantra and theology speaks of Jesus’ Last Words to them, “Do nothing until I come back.”

Count a hundred of them before you find a cell phone. So you burn your trash, feed table scraps to the chickens or land crabs, break your rum bottles and sink them in a thousand feet of water, all perfectly legal and socially acceptable. After all, some places, a thousand feet is only a quarter-mile off the reef. The shards grow coral, more fish habitat.

Clink, clink, clink.

All fine till we ran short of diesel. We eased across the inlet to Norman’s Cay.

“No mon, dere is no diesel here. Don’t worry, mon, fuel barge soon come.”

But there was diesel there, quietly reserved for the locals who fueled diesel generators for household power.

Howie and Scottie met her at a beachside bar. She called herself Yellow Bird on the VHF.

“Sportfisher, Sportfisher, you got any meat for me?”

She was blonde, round and smiley, formerly the child bride of a pilot doing time for flying coke for Carlos Lehder. Folks said Hubby buried money in Panama before he got busted, but only he knew where it was, so she was waiting for him to get loose and dig it up. But she was not waiting too hard.

The cartel took Norman’s Cay, storming ashore with a cadre of Vopos, East German border guards suddenly out of work when the Berlin wall came down. Vopos went door to door.

“Señor Lehder is very concerned about your personal safety,” they recited in broken English. Forty-odd homeowners packed up and fled. Lehder ran Norman’s Key like a fiefdom, 60 tons transported to Miami in his best year. He was a charming host, by all accounts, sending Jeeploads of naked women to pick you up at the airstrip, but if he didn’t know you, you’d be looking down the barrel of an M-60 machine gun instead.

“Señor Lehder is very concerned about your personal safety.”

Indeed.

Finally the DEA swooped in with token Bahamian support. The Vopos ran for the mangroves, the pilots were too stoned to fly. Locals stole everything they could carry – carburetors, injectors, batteries. Lehder spent a single night in jail, then vanished after a courier delivered one million U.S. to Nassau and nobody saw hide nor hair of him for the next seven years.

But to the matter of Yellow Bird and diesel fuel. Not sure what Howie and Scottie promised or delivered, but when we eased to the beach about sunset, there was 40 gallons of diesel in jerry cans hidden beneath a pile of fresh-cut palm fronds. We ferried them out to Maggie C in a Zodiac skiff, poured them down a funnel cut from a plastic milk jug, enough fuel to get back to Nassau, maybe even a little more. So now we were off the reef in a thousand feet of water, busting rum bottles over the side – clink, clink, clink.

“Reckon we might fish so long as we’re out here?” Howie was at the helm. Scottie was laid up ashore, his back tore up from wrestling jerry cans from the Zodiac. “What we got for bait?”

I took inventory. “Just some mushy ballyhoo,” I said. Ballyhoo run about six inches and are generally sold salted like herring, with a length of fine copper wire run through the head to keep them on the hook while trolling. Run a Technicolor-fringed skirt up the leader, thread on a ballyhoo, pull the skirt back over the eye of the hook, and your rig looks like a Barbie Doll dressed up for Mardi Gras, lays a sent trail like a hundred-dollar Bourbon Street whore. Sailfish will hit them; mahi will tear them up.

“Get them lines in the water!” I did, then went back to my chores – clink, clink, clink.

Pretty quiet till we crossed the deep channel just north of Norman’s. The rods were free-spooling with the clickers on. One took off, buzzing like a canebrake rattlesnake. Then another, and finally the third. Three fish hooked up, I dropped the last two bottles. They bobbed astern, fully afloat, a violation.

Howie threw Maggie C on autopilot, rushed to lend a hand. Two men and three fish – Great God Almighty! Auto-pilot couldn’t hold her, and the boat soon swung broadside to the oncoming sea. There was a serious scramble on the slippery aft deck.

The fish were crossing, crossing again, fixing to tangle. One rod was bent about double.

“Can you hold that big bastard,” Howie asked, “till I get these little farts aboard?” ‘

“I’ll try,” I said.

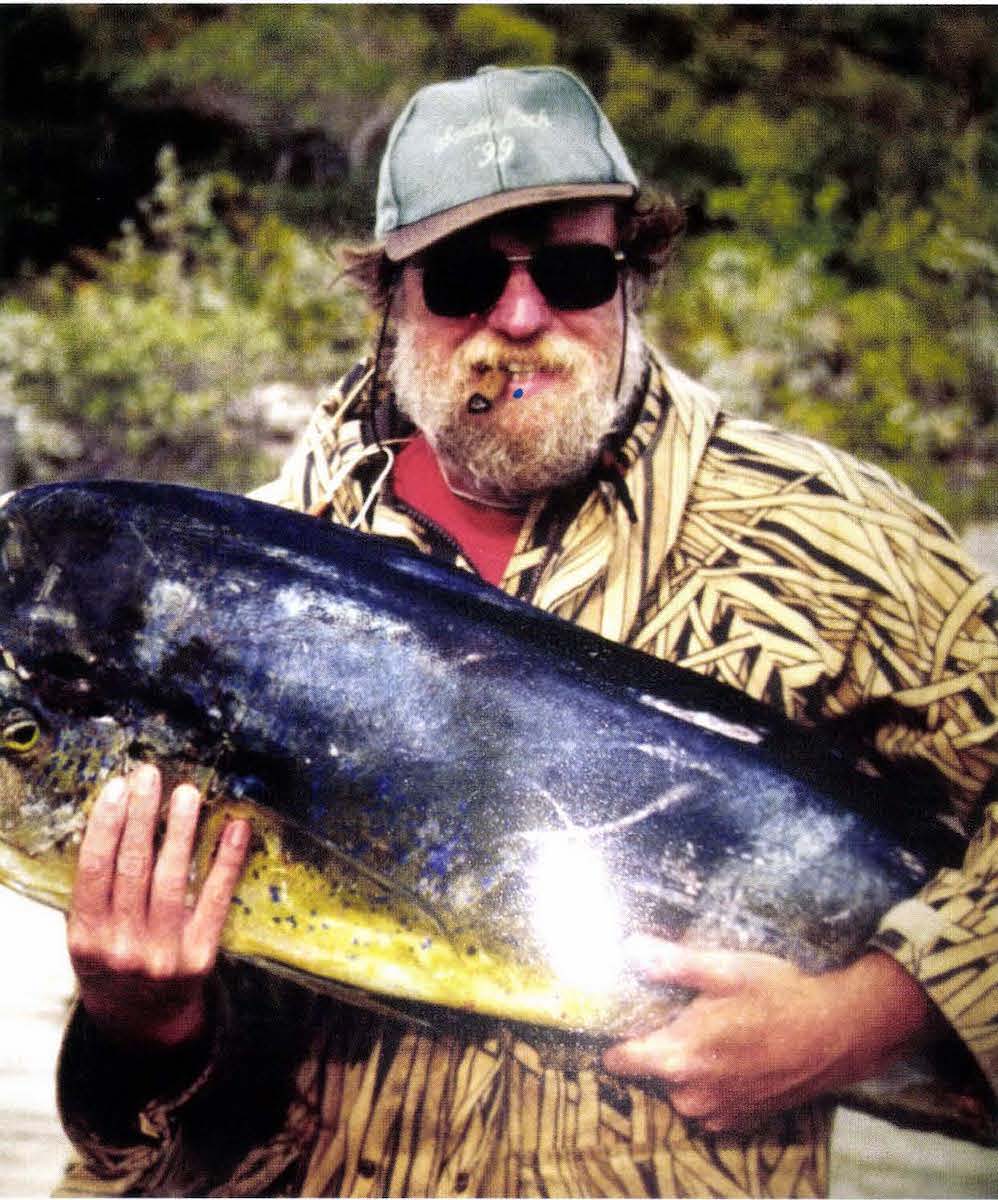

Howie bore down on the drag and a fish broke water 50 yards astern. Mahi, 25 pounds, leaping like a Polaris missile, twisting, thrashing like an acrobat, neon blue and 16 shades of green. It tail-walked, shook its head and the Barbie Doll lure rattled off his jawbones, whackty, whackety, whack. Howie tried to horse the fish aboard. Ever seen a man fight a fish and gaff it too? I saw it then.

Still full of fight, the mahi ricocheted around the cockpit and two days later, the both of us were black and blue from ankles to knees. But that didn’t matter right then. The fish almost went overboard. I left my reel and dove atop it, and Howie grabbed the fish billy, a 16-ounce claw hammer loose on the handle. By the time we wrastled it into the fish box, we were all slobbered with blood, saltwater and slime. Then we turned and quickly boated the second fish.

The third fish was a jumper. A perfect arc, right to left, left to right, like some old-time carnival shooting game. I held that big bastard and my back still hurts whenever I think about it. The drag was howling. I keyed the mike, VHF 16, held it to the reel. I knew Scottie and Yellow Bird were listening. I was a mean man back then.

A Bahamian dock is just like a Bahamian everything else, perilous in the extreme. Howie knew his way around a fish, his knife was shaving sharp and flew three ways, high, wide and frequent. I swabbed the deck, tossed the mangled ballyhoo overboard. I washed the cooler and a gallon of blood drifted down the tide. Wasn’t long before a ten-foot bull shark came nosing.

The three of us were on the end of the dock, along with 40 pounds of dripping mahi on the skinning table when the shark made its first pass. Second pass Howie was ready, or at least he thought he was. He wrapped the mahi skins in a length of cheap rope, threw them overboard. Trouble was, the other end was tied to a dock pole.

When the shark hit the end of the line, it came up, shook his head just like those mahi did. The dock bowed, creaked, groaned, sagged. We ran like hell.

“Grab the fish,” Scottie hollered. “Get the fish!”

Nobody did. The shark tail-walked once more, gnawed through the rope, fell back into the water with a mighty splash, then swam peaceably away with the mahi skins crosswise in his maw. Four-foot rays eased in and sucked up the scraps.

“Holy crap,” Howie hollered, “did you see that?”

“See it?” I hollered back. “I damn sure saw it!”

Howie shook his head, took a deep breath. “We got ice for these fish?”

“I think so,” I said.

“Cooler ’em up. We gotta hit Nassau before sundown.”

We loaded the fish, fired the diesel, pulled away from the dock.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

Read on as some of the sport’s most talented writers recount their personal memories of catching bass, trout, bluefish marlin, tuna, and more. Explore the Pacific with Zane Grey, as he fights a 1,000-pound blue marlin, or listen as A.J. McClane explains just what it really means to be an angler. Take a step back in time when you read Ernie Schwiebert’s tale of fishing a remote lake in Michigan, when he was still only a young boy. Each of these stories, selected because of its intrinsic literary worth, reinforces the unique personal connection that fishing creates between people and nature. Buy Now