An excerpt from Ruark Remembered by Alan Ritchie who served as Ruark’s personal secretary for 12 years.

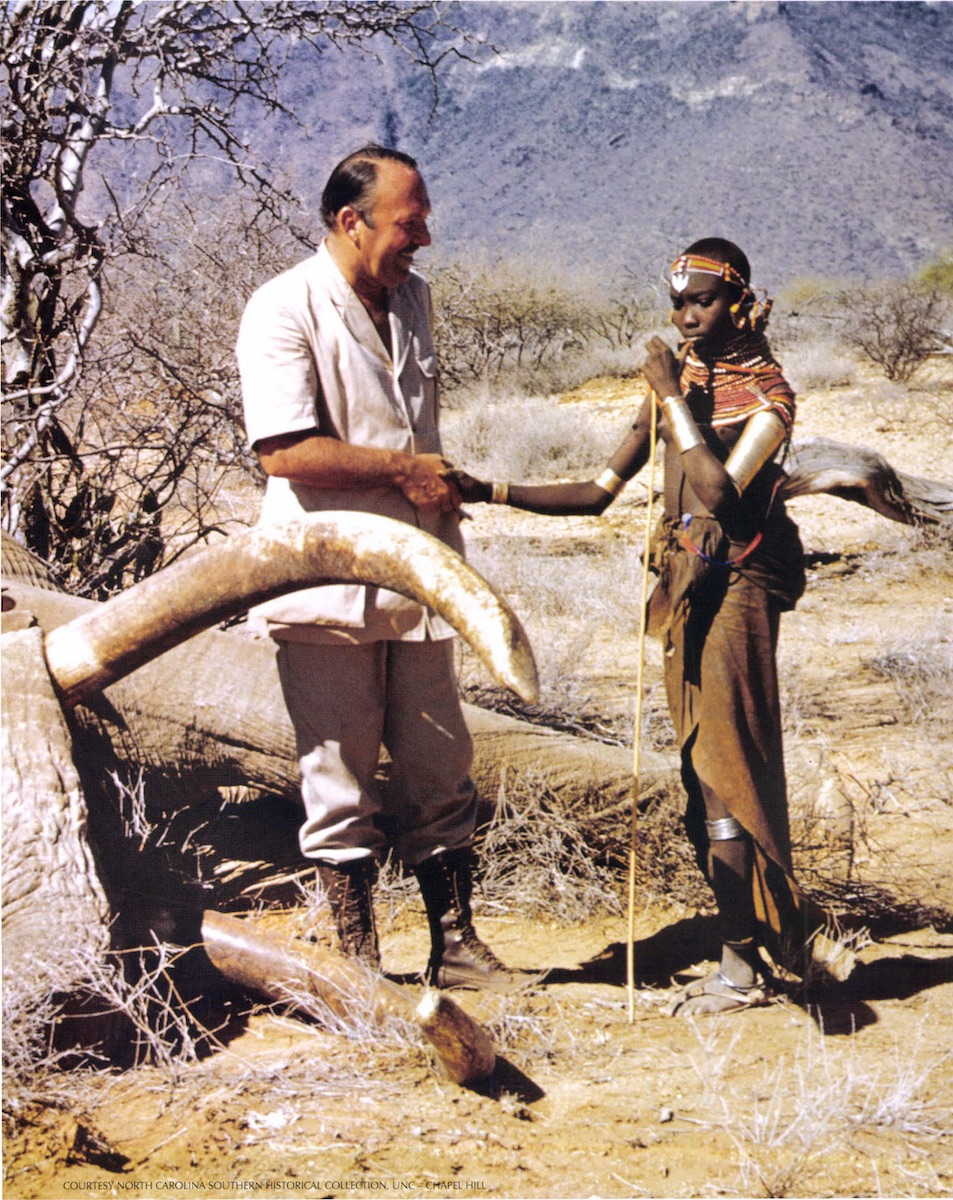

Then finally the day came, and as it so happened with the aid of a ten-year-old Samburu-Rendille maiden, that Bob got on the trail of what promised to be very big elephant.

Bob wrote:

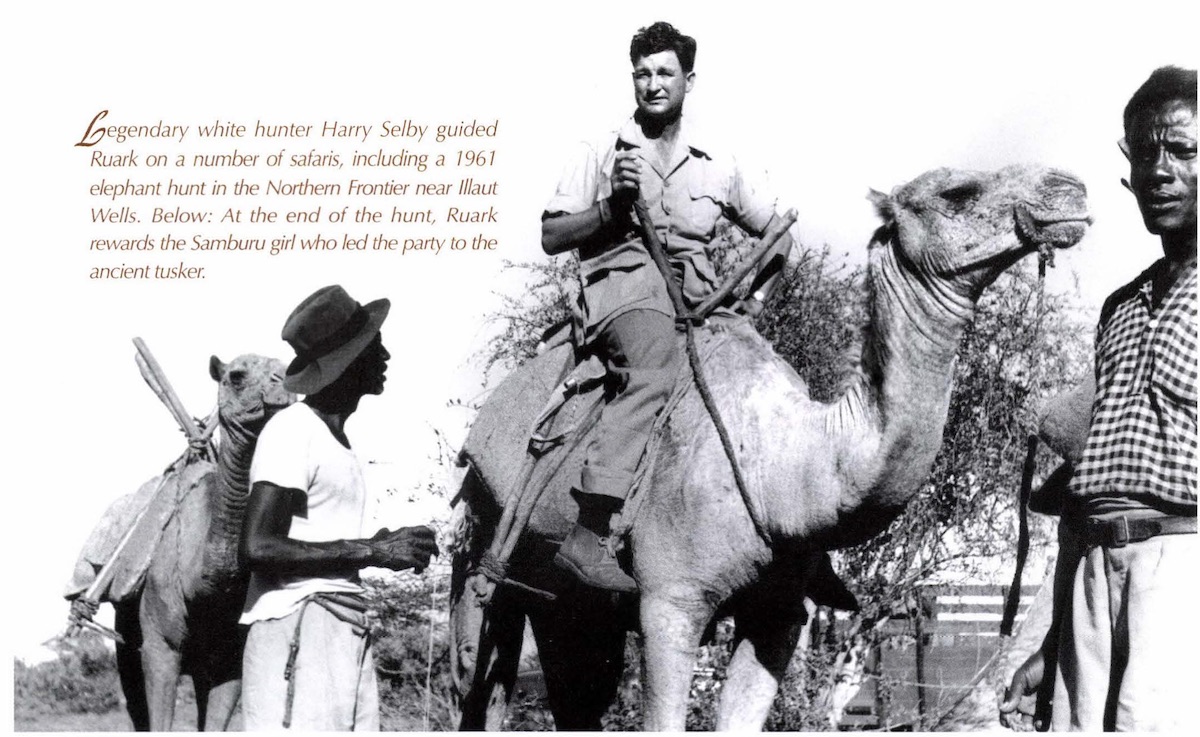

We jogged the nags to a little hill and climbed up it just as the sun began to paint the stern blue mountains and the sere brown of the scorched wasteland. Selby and Metheke had the glasses, and they began to sweep the terrain. Suddenly both Africans—white Selby, black Metheke— began to coo. “Ah-ah-ah-ah-a h-AH-EEEEE!” both Africans said, in a rising scale that lilted to a falsetto. “Ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-AH-EEEEE!”

They turned, beaming, twin-like despite the disparity of race and color, soulfully in delight. They handed me the binoculars, and pointed. Something filled the binoculars and suddenly, I began to coo, too. “Ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-AH-EEEEE!” I crooned. Then we all slid down the hill and kicked the horses into a trot. Cap’n Ahab, crudely adapted to camels and Somali ponies, had finally raised Moby Dick.

In many columns written while on safari, Bob included some reference to Hemingway, and he would have had in mind his old friend when reporting the end of the hunt for the “impossibly big and old elephant.” He fittingly entitled the piece “Death in the Afternoon.”

The old man was old, very very old. He had lived too long. It was possible that he saw the 18th century change to the 19th—the 19th switch over to the 20th.

For many, many years—as long as the few permanent natives could remember—he had lived on Illiat. He came to drink every day at the waterhole a few hundred yards away from the Somali dukah, or tiny tin-roofed shack.

Ruark extends thanks to a Samburu girl who led him to his last elephant on his hunt in the Northern frontier district in Kenya.

He was long past breeding—long an outcast from the herd. His memory of women and palm toddy were dim. The young bulls no longer came to him for counsel, although his accumulated wisdom was vast. He had long since run through his repertoire of jokes, and no longer found listeners for belly rumbling, nostalgic tales of the good old days before the white man came with guns—the quiet good tales of the good old days before iron birds made cloud-tearing noises in the blue Kenya sky as they flew toward Ethiopia.

He was deaf, possibly, and certainly his eyesight was dim. His great ears, which once clapped like thunder as he flapped at flies, or shook furiously as he screamed in anger and charged, now hung in shreds; hung limp and fluttered feebly as he waved them. Over most of his back a mossy excrescence, like barnacles on an ancient turtle or moss on rocks, grew thickly. He was pitifully thin, tremendously wrinkled.

There would have been the curious growths inside his belly that very old elephants have, and the enormous black tusks would be too heavy to carry in comfort now that so much weight had left his other end. How he had reached this age without breaking one or both tusks was a mystery. But there they were, great ivory parentheses stretching low and upward from his drooping lip.

He rocked and grumbled to himself, as old men will, and the litany of complaint was clearly audible on the wind as we walked close, leaving the ponies tethered to a thorn bush. He had been a traveling man in his time—he had possibly been to Ethiopia, to Uganda, even as far as Rhodesia. He knew Tanganyika well. But now he was all alone—chained by necessity to the creaking rocking chair of age.

All the cows and calves and younger bulls—who tolerated his presence at the waterhole—had gone over the mountain to the green, following the rains. But he was too old to trek with them— too feeble.

He was alone because he could not leave certain water. And he was starving himself, because he could not graze for more than a five-mile area from that water. The forage was almost gone, because of the three-year killing drought and because he had eaten down the land to rock-hardness.

He was all alone, and soon he would die.

Unless the rains came to green his prison area, he would die, of senile decay and lack of nourishment and, most of all, of boredom.

There he stood, alone and magnificent on the slope of a sere brown rise with a harsh, cruel, blue hill behind him. There he stood, his two enormous tusks a monument to himself, and a monument to the Arica that was—the Africa that had changed, was changing.

“Poor old beggar,” Harry Selby muttered. “Poor, poor old boy.”

I am an elephant hunter, so I will not say my eyes were misty when I shot him twice through the gallant old heart. They misted after, yes, but we had come to find a testimonial to another age and the way to keep him was to shoot him. He lurched to his knees, recovered, staggered a few yards and died in midstride. He fell with a mighty crash, splitting a tusk, and when he died, old Africa died with him.

The shooting of this grand old elephant gave way to a feeling of anticlimax, as the search had been so long, and the coup de grace had come on practically the last available day, because Bob had given up his high hopes and was preparing to leave the area immediately for Nairobi. Later, when weighing the tusks at an Indian dukah, there was some disappointment. Because the elephant had been so old and thin, the tusks had appeared much bigger than they really were. Still, they went over the 100-pound mark, weighing out at 101 pounds on one side and 103 pounds on the other.