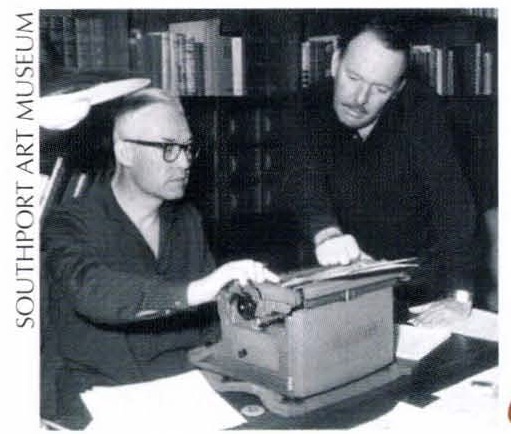

Alan Ritchie served as Ruark’s personal secretary for 12 years.

An excerpt from Ruark Remembered by Alan Ritchie who served as Ruark’s personal secretary for 12 years.

I had a feeling that Hemingway’s death affected Bob more than he would have admitted at the time, and, during the remainder of the safari he was puzzling out a problem…the destruction of a writer…and why?

Around the campfire quite one evening, after everyone else had gone to bed, Bob began to talk about Hemingway. He recalled some of the writer’s past and his great writing ability and, in Bob’s opinion, the eventual decline of this ability. He noted how as long ago as 1955, when he had finished Something of Value and was in the States enjoying its terrific success, he had deliberately avoided contacting Hemingway. This was because Bob had heard he was having some trouble with his latest novel, and he didn’t want to embarrass his old friend with his presence at a difficult time.

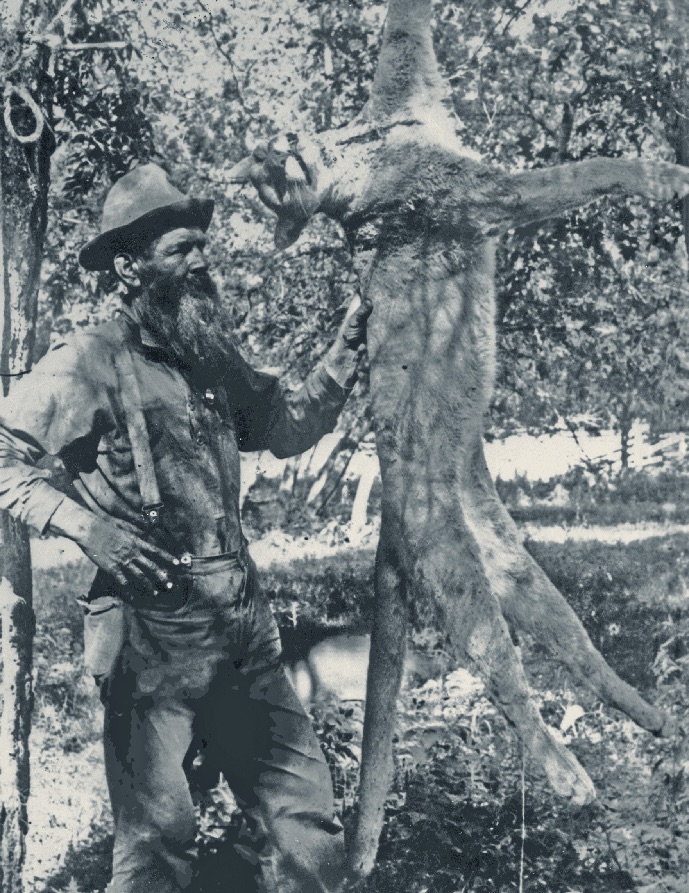

Ernest Hemingway with a Cape buffalo he took in Kenya in 1934. This buff was brought down with his much loved Griffin & Howe Springfield .30-06.

Although Bob had a great admiration and affection for Hemingway, he continued at length to make a strong point that he, in fact, knew Africa better. He had been there more often and had traveled far more and had far more safari experience than Hemingway. In addition, he’d had the advantage of jet aircraft, something that made an enormous difference to the world traveler. Then Bob turned to his frequently expressed objections to criticism that he had copied Hemingway. He denied angrily that he had ever done so. He said the fact they both had been to Africa and Spain was sufficient for some critics to make this accusation, but that they conveniently overlooked the fact that a great many other people had also traveled to these places.

Robert Ruark stops a charging rhino during the filming of African Adventure, a full-color movie that first appeared in theaters in 1954.

After a lengthy silence, during which we both stared into the campfire, Bob got up to replenish his whisky glass and to kick the fire into a crackling roar with the aid of an abundant supply of fresh logs, something he loved to do. Reseating himself on a large log, he then expounded on what was really worrying him—the possibility of a prolific writer running out of words and arriving at the stage of being unable to write.

A great many people would have wondered why a man like Hemingway wanted to shoot himself, why he couldn’t have relaxed and enjoyed his successes, and perhaps written a little when he was able. But I could see very clearly that Bob knew why. I believe that it frightened him that he would one day arrive at the same point, and maybe at this moment he decided he would not allow it to happen. Authors have a habit of destroying themselves, but there are various means of self-destruction. Robert Ruark was never a potential suicide—not with a gun, that is! He used other means to destroy himself.

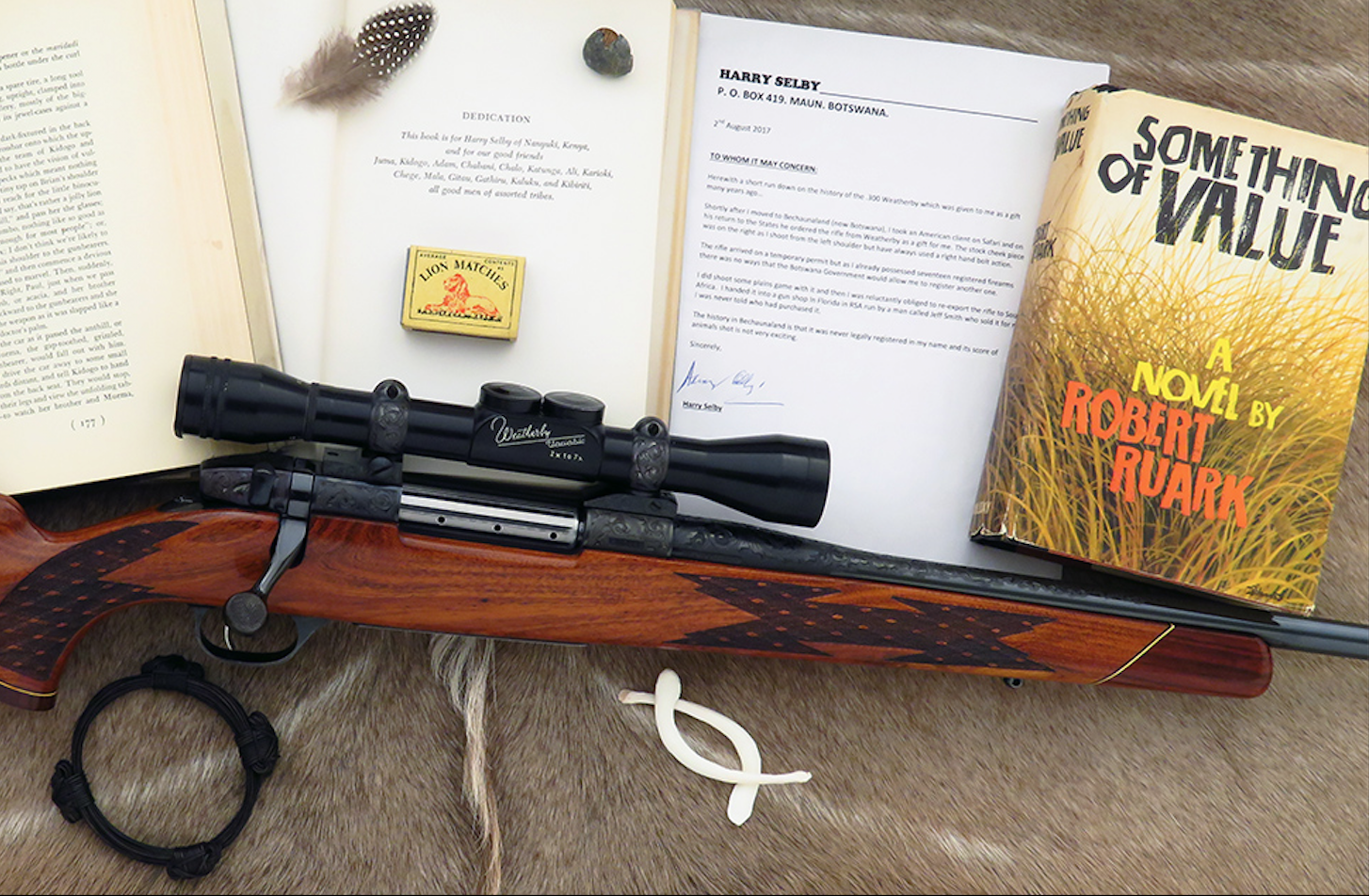

Ruark killed this huge bull elephant while hunting in northern Kenya in 1953. The tusks weighed 109 and 110 pounds. With Ruark are professional hunters Harry Selby (center) and Andrew Holmberg.

Later in a column Bob wrote:

I hunted hard for three weeks in new country, and I couldn’t get Hemingway out of my mind. We were friends and I greatly admired some of his work, but I did not think his work was flawless. He preyed on my mind. And one day when I shot a very old elephant, I sort of got rid of brooding about Papa. What bothered me, I think, was that both Hemingway and Negley Farson had died more or less by their own hands in the last year. Farson didn’t actually kill himself—he wore himself out just living hard and free. But to me, both writers stood for something that we seem to be running short of. I am talking of manhood, pure and simple, and the uncontrived joy that man has always derived from hunting and fishing and camping and fire light and good bourbon and a reeking pipe and a sound collection of poker players, who also tell tremendous lies about past exploits, which have become fact instead of fancy merely by the rubbing of frequent usage.

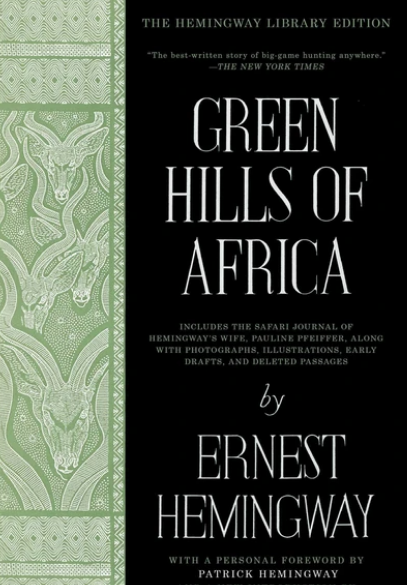

When it was first published in 1935, The New York Times called Green Hills of Africa, “The best-written story of big-game hunting anywhere,” Hemingway’s evocative account of his safari through East Africa with his wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, captures his fascination with big-game hunting. In examining the grace of the chase and the ferocity of the kill, Hemingway looks inward, seeking to explain the lure of the hunt and the primal undercurrent that comes alive on the plains of Africa. Green Hills of Africa is also an impassioned portrait of the glory of the African landscape and the beauty of a wilderness that was, even then, being threatened by the incursions of man.

When it was first published in 1935, The New York Times called Green Hills of Africa, “The best-written story of big-game hunting anywhere,” Hemingway’s evocative account of his safari through East Africa with his wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, captures his fascination with big-game hunting. In examining the grace of the chase and the ferocity of the kill, Hemingway looks inward, seeking to explain the lure of the hunt and the primal undercurrent that comes alive on the plains of Africa. Green Hills of Africa is also an impassioned portrait of the glory of the African landscape and the beauty of a wilderness that was, even then, being threatened by the incursions of man.