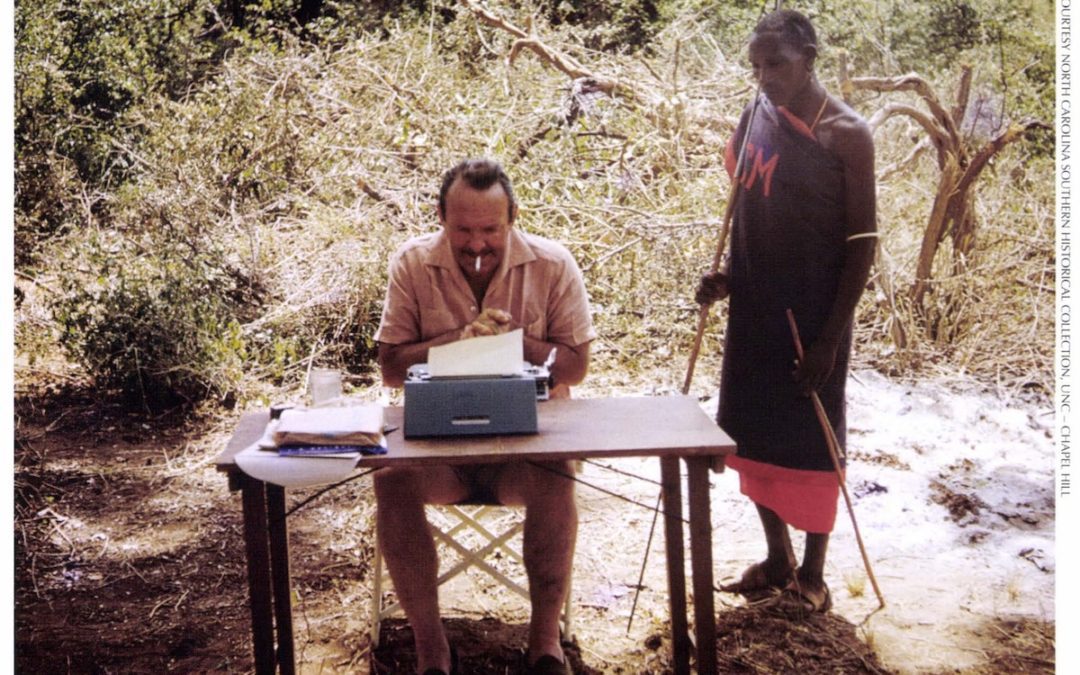

An excerpt from Ruark Remembered by Alan Ritchie who served as Ruark’s personal secretary for 12 years.

During the next few weeks we’ve changed locations many times with a series of fIy camps, sometimes setting up without anything except mosquito nets. The whole experience was intriguing. I must admit, though, sometimes at night in a half sleep I found that a camel’s grunt sounds awfully like a lion’s roar.

On one of these moves we had been going all day with the horses and had ridden or walked a good 25 miles over boulders, rocks, dry riverbeds, and dusty game trails. The temperature was stifling, and on arrival at our new camp, we were all completely dehydrated. I even felt as if I had a touch of sunstroke. While everyone else settled down to drink tepid soft drinks in order to come back to life, after a slight attempt at one Seven-Up, Bob turned to the gin bottle and proceeded to quench his thirst with half glasses of neat gin.

On these occasions Harry Selby and I became very nervous, and we couldn’t really look at Bob when he was drinking. Selby had all too clearly in his mind what had happened the previous year in Nairobi and various other places. He had seen the result of Bob’s excessive drinking, and the collapses and fits that followed. Although Harry was frightened that Bob was drinking so heavily there might be a repetition, it seemed extremely difficult for him to try and stop a client from drinking, just as difficult as it was for a secretary to admonish his employer. We were particularly worried because if Bob collapsed here, it would be many days before he could receive proper medical help.

Fortunately, nothing serious happened. The safari progressed and the campfires at the end of a hard day were a delight. We had many hours of good conversation around the fascinating light of flickering fires in the middle of nowhere. I noticed that Bob would sit staring into the log fire after everyone else had turned in, though this was normal for him as he never went to bed early.

The safari was on the whole a happy one. Bob was enjoying everything and I was still wide-eyed at everything. Still, I worried a little more each day about Bob, because he appeared to be drinking at an increasingly high rate. I think he was inclined to give the impression that because of his contentment on safari, he tended to drink far less, though I would say from my observations this was opposite the truth. For one thing, the fresh air and exercise made him feel fit and probably increased his tolerance for alcohol. Also, Bob was a great one for the satisfying drink, and no better place to enjoy a bottle of whisky can be found than around a campfire after a hard day in the bush.

We had been out a number of weeks when we began to realize that we probably would not find any big elephants. It was so terribly dry they were no doubt all on the other side of the Matthews mountain range where there would be suitable green forage after rains in that area. Still, as we searched for an elusive big elephant, we were sufficiently entertained by fascinating countryside.

It is a fantastic county—scattered aimlessly around as if God just got tired packing and threw His leftovers out the window. Its mountains are aimlessly placed, and the people, what there are of them, match the mountains. It is desert-hot, hence the camels, and dry as the martini I wish I had but haven’t.

I have seen all of Kenya, save this area before, and some of Kenya is unbelievably beautiful—soft and cool and green and vibrant with life. But I like north country best, I think, possibly because everything and everybody in it is lean and hard and tempered to tough times as a steady diet. Everything in the north is functional. Either it is functional, ascetically honed to the bone, or it dies.

But man has not trampled this land, and nearly everything we have done so far has comprised a “first,” which is telling in itself. The country is exactly the same as it was since the day the great earthquakes tore the African continent apart and created the Great Rift Valley. There must be elephants here who were born before 1800, and although the object of this safari is to find and shoot some monster bull whose tremendous teeth are achy and whose ancient bones are weary of seventy years of ceaseless searching after water, I really don’t care if we do or not. It is enough, in this harassed and confused world, momentarily to enjoy the simple act of wandering lonely as a cloud through a vast wasteland, which was never seen even by the first white man who clapped eyes on this part of the continent. —Robert Ruark