One of the redeeming features of existence in a small Canadian town is that at all seasons of the year some form of woodland sport lies within an hour’s walk or drive or paddle of your door. For the monarch moose and the shy, capricious caribou, one must go far afoot. All other kinds of game that offer reward for the hunter’s toil may easily be found and brought to bag within the compass of the short autumn day. The Divide between Clearwater River and Shanley Creek, in western Montana, was covered with a four-foot burden of crusted February snow, when Mr. De Witt, hunter Jim Culbertson and Indian guide Tah’won left camp on the Clearwater. The object of the party was, if possible, to capture a bull elk alive and bring him in a prisoner.

The conditions were favorable, for whilst the crust would readily bear a man on snow-shoes, it was not strong enough to support an elk or a deer for an instant.

They started on skis, or Norwegian snow-shoes, made of wood, eight feet in length, six inches broad, and half an inch thick. These skis—more suggestive of snow-skates than shoes—are turned up in front something after the fashion of sled-runners, and a man skilled in their use can travel at surprising speed over good snow. In addition to the shoes, the party was equipped with lariats, one large toboggan and three pairs of netted snowshoes for use in the timber.

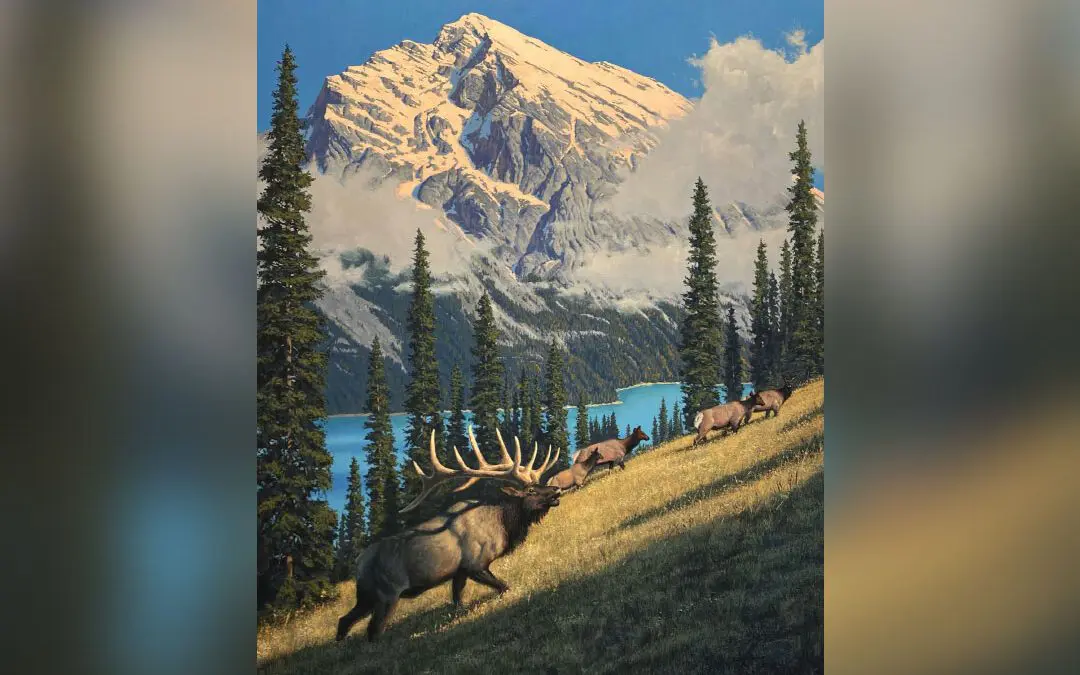

The western slope of the Divide is a succession of benches and rolling foothills, extending from the Clearwater nearly to its summit, before the timber is reached. On the east slope are numerous little parks in the timber, many of them marshy, having living springs that do not freeze except in the most severe weather. In such spots the tall swale-grass grows luxuriantly, and they are generally surrounded by thick bushes, while all about in the woods are large trees and no underbrush. In these parks the elk like to winter. Sheltered by the timber and the bushes, they paw through the snow to the tall grass, browse on the brush and, having plenty to eat and drink, are content unless disturbed.

After shoeing for about two-and-a-half hours, the party reached the summit of the Divide and separated—Jim Culbertson making a circle to the right and Tah’won to the left—leaving Mr. De Witt with the toboggan. In 20 minutes Tah’won signaled Mr. De Witt that he had found “sign.” Mr. De Witt signaled Jim to return, and they cautiously followed. The Indian, Tah’won, had discovered where the elk had been browsing and, following up the sign, led them down the east side of the Divide near to a little park. Moving carefully around from the windward they reached the park, and found the snow tramped down by the hoofs of game. Evidently the elk were yarding there.

Looking cautiously through the cover they enjoyed a revelation of beauty sufficient to warm a sportsman’s heart. There stood a family of seven elk, and among them one large bull. The keen-nosed game presently winded the intruders, and the big bull, with an impatient stamp of his foot, turned toward the foe. His mighty head held high, nostrils dilating and eyes blazing, gave him an air of mingled curiosity and defiance. The other elk bunched behind him, ready to fight or flee. It was a striking picture, worthy the brush of Landseer. A white ground of smooth tramped snow, framed by a circle of red and gray bushes, tall, straight pines and larches in the background. In front, standing in bold relief, the antlered monarch of the mountains, and grouped behind, his handsome family, waiting for his signal.

“Thet thar elk ’e’ll weigh nigh a tho’sand pounds, an’ his antlers is six foot long, wi’ a spread o’ four foot at the pints,” whispered Jim, “an’ ’e’ll give us a right smart tussel, but we’ll captur’ him ef you say so.”

Jim gave a shrill whistle as he stepped into the opening with his rifle thrown across his arm. The elk gave a whistling snort, turned and, with a shambling trot, went across the park, jumping into the deep snow.

The Indian ran, coiling his lariat as he went into a large loop. Coming up with the bull, which was in the lead of the band floundering in the snow at every jump, Tah’won threw his lariat, which uncoiled in circles. As it fell, the bull threw up his head disdainfully, his nose struck the lower part of the coil, knocking it up, and the lariat tightened about his antlers only.

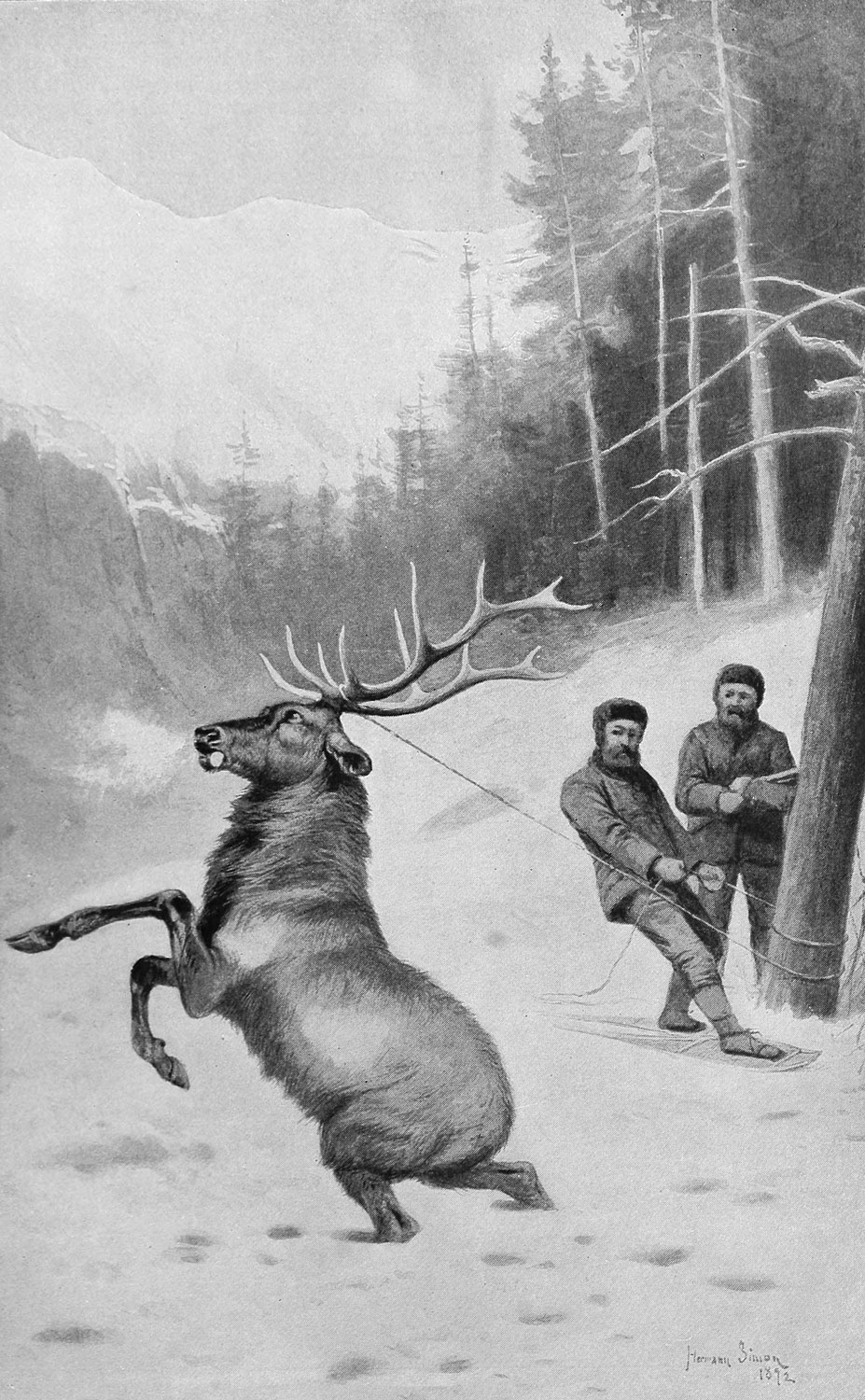

As soon as the lariat was thrown, Tah’won, keeping hold of the end, turned to run, but, unfortunately, his snow-shoe caught in the limb of a fallen tree in the snow, and he was thrown forward on his face. As he fell he gave one frightened, expectant look back over his shoulder. The elk did jump toward him, but being deep in the snow when he jumped, struck his breast against the same limb of the tree and was knocked back. At that moment Jim, coming from behind, quickly raised his rifle but, seeing Tah’won once more on his feet, did not shoot. Quick as a flash the Indian took a turn with his lariat round a tree before the elk had recovered from his fall. But in another instant the elk was on his feet again and, finding himself fast, jumped and bucked in the wildest manner. The other elk, after running off a little way into the timber, stood anxious spectators of the scene.

Tah’won now showed himself a little to one side of the tree, and the enraged elk, with a snort, immediately charged.

Taking in the slack as the elk came on, Tah’won fell back to the next tree and made his lariat fast. Then, taking another lariat, he slipped behind the elk, which had trampled the snow down all about him, and was still jumping and plunging to the extent his short rope would permit. Throwing the lariat again skillfully, he caught both hind feet of the elk in it, and the animal was stretched and thrown. The second lariat was made fast to a tree behind, and in a few moments the bull was secure.

The men then sat down to recover their breath, for waltzing around on snowshoes is rather awkward unless one is used to it, especially if disposed to be “pigeon-toed”—in that case, one wearing web snow-shoes must, as Jim expresses it, “step high, wide, and han’some.”

Tah’won was the first to recover himself, and remarked, “ H-e-a-p big el-lock. Ugh! ’most catchee Tah’won!”

“Yes,” said Mr. De Witt, “he would have caught you if the limb of the tree had not knocked him back in the snow and, if he had, the sharp hoofs of his forefeet would have pierced your body, and like enough he might have picked you up and given you a ride in that cradle he carries on his head.”

“Ugh, no! Big hunter Jim shoot ’em el-lock!”

“No, Tah’won, ef he hadn’t a-bin stopped in his fust jump, he would hev reached you, sartin, becase the bushes was atwixt him an’ me, an’ I couldn’t see ter git a shot. But now we’ll try to give him a ride.”

Jim brought around the toboggan, the elk was rolled on it and made fast, and then came the tug of war. The three men moved the game where the snow was trodden down. When they came to the untrodden surface they could not draw the toboggan up on the crust, which was not as strong in the timber as in the open. The edge of the crust broke down with the weight on the toboggan, and they soon became convinced that they were stalled. They had captured more spoils than they could retreat with. But unlike the Indians who kill the captives they cannot get away with, they determined to brand the captive and let him go. So a string was tied about his neck in token of his captivity. While Tah’won unbound the elk, Jim held him down by his horns until all fastenings were off save one lariat, which was kept fast with a slip-noose around both hind feet, the other end being fast to a tree. When all were well out of the way, the lariat was cast off from the tree, and the elk soon recovered himself; the loop, loosening, dropped from his feet and, with a bellow, he started for his band.

“Mr. De Witt,” said Jim, “you hev put your brand on ’im. I’ll brand ’im so we’ll both know ’im next time we see ’im.”

He quickly brought his rifle to his shoulder and put a bullet through the left ear as the elk ran directly away.

Determined not to be entirely foiled, they made haste to overtake the band and capture a small elk that could be handled. Speeding on their wood shoes nearly as fast as they could have gone over the ice on skates, they soon came up with the band, which was making slow progress by floundering through the snow.

Tah’won had to be wary in approaching the band, for the big elk was still mad and would charge at the slightest provocation. After a little, the Indian selected and caught a young bull from the rear of the band. This one was about 18 months old and, with the help of Jim and Mr. De Witt, he was soon bound and lashed to the toboggan. For a short distance, until they reached the summit of the Divide, the men had load enough and were compelled to rest frequently. But gradually the party worked their way back from the hills, the elk riding his toboggan, and as much frightened as an animal could possibly be. At sunset they reached camp on the Clearwater where the captive was made comfortable in a stall in the horsebarn. And so ended a novel and most extraordinary experience.

This article originally appeared in the February 1893 issue of Outing.