A raging wildfire threatens to bring President Roosevelt’s safari to a quick and untimely end.

It was a terrifying sight that greeted Theodore Roosevelt as he stepped from his tent that morning in 1910, and it was something that could have brought a costly and premature end to his great African safari.

TR looked in horror as a raging fire roared toward him and his camp. Flames leapt high in the air as the fire raced through the tall, dry grass. Lions could be heard in the distance roaring their disapproval and flocks of birds flew frantically in all directions as they escaped the approaching flames.

The President was coming to the end of his African safari and had made camp in the Lado Enclave, a small strip of land in the former Belgian Congo, south of what is now southeast Sudan and northwest Uganda.

In December 1909 King Leopold of Belgium died, which left this Belgian outpost without a governor. As a result, it became a no-man’s land of lawless elephant poachers. It remained like that for almost a year, until it was decided who should be in control.

TR, however, had been granted special permission to hunt white rhino there, to complete the requirements of the National Museum in Washington, DC.

Half of the President’s safari was camped farther upriver where R. J. Cunninghame, the safari leader, along with zoologist Edmund Heller and their native helpers were working as fast as possible to prepare the skins of rhinos already collected.

Back at the main camp, TR knew that he had to move fast if he was going to halt the fire. So Kermit, the president’s son; Edgar A. Mearns, the safari’s physician; zoologist J. Alden Loring; and Quinton O. Grogan, one of the last great elephant hunters who had recently joined the safari–all pitched in to help the natives dig a network of fire lanes around camp.

They knew that if they couldn’t hold back the fire, it would soon engulf the tents and they would lose everything.

Other members of the safari were too far away to come to their rescue, and unknown to TR, Heller and Cunninghame were fighting their own battle. Apparently, the lions TR heard beyond the fire had been driven toward Heller and his skinners, trapping the men in their temporary camp.

At the hunters’ main camp, every available man was put to work digging and setting backfires on the other side of the fire lanes; others stood by with tree branches and wet gunny-sacks to beat out the flames should the backfires need controlling.

As night approached, the fire swept into a vast stand of papyrus and the flames climbed 50 feet into the air. The men continued to work late into the night as the fire raged toward the camp. They watched helplessly as scattered, wind-borne flames, which appeared to be dying, dropped onto small thorn trees and crackled back to life.

TR and his native helpers struggled to move valuable equipment and goods to the other side of the camp away from the fire. All night the men watched as the flames danced around their camp.

As morning approached they could see their backfire, now almost 100 feet from camp, about to meet the wildfire as it crested a small hill. As they met, there was a huge, crackling roar, and then the fire died down and slowly burned out.

TR breathed a sigh of relief as the opposite edge of the fire cast an eerie glow over the savannah. As the smoke slowly drifted away, TR could once again hear the lions, their roars growing louder and louder as the big males called desperately for their mates across the smoldering savannah.

As the sun rose into the African sky, birds of all kinds chirped and chattered into view as they scratched across the charred land looking for insects. TR was intrigued to see the larger animals return to their normal feeding patterns, even though small flames danced only feet away from their heads.

The fires continued to burn for several days, but they did not threaten the camp again, and TR and Kermit resumed their hunts for white rhino.

Heller and Cunninghame returned to the main camp the next night, surprised to see what the President had to contend with during their absence. It’s safe to say there were many stories told at camp that night.

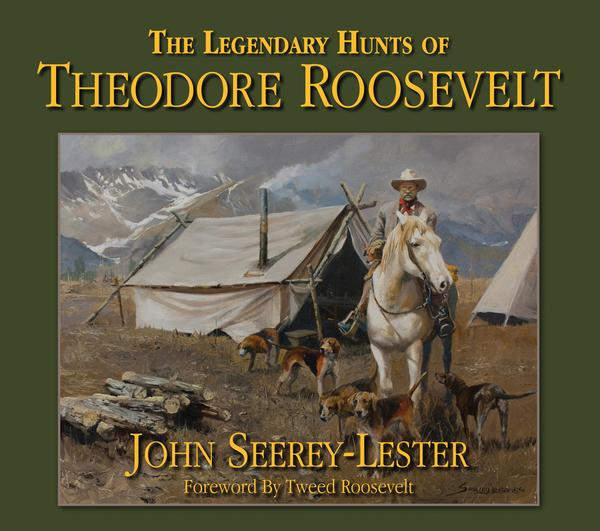

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now