“The man should have youth and strength who seeks adventure in the wide, waste spaces of the earth, in the marshes, and among the vast mountain masses, in the northern forests, amid the streaming jungles of the tropics, or on the deserts of sand or of snow. He must long greatly for the lonely winds that blow across the wilderness and for sunrise and sunset over the rim of the empty world . . . He can journey through the northern forests, the home of the giant moose, the forests of fragrant and murmuring life in summer, the iron-bound and melancholy forests of winter . . . ”

“The man should have youth and strength who seeks adventure in the wide, waste spaces of the earth, in the marshes, and among the vast mountain masses, in the northern forests, amid the streaming jungles of the tropics, or on the deserts of sand or of snow. He must long greatly for the lonely winds that blow across the wilderness and for sunrise and sunset over the rim of the empty world . . . He can journey through the northern forests, the home of the giant moose, the forests of fragrant and murmuring life in summer, the iron-bound and melancholy forests of winter . . . ”

So wrote Theodore Roosevelt from his home at Sagamore Hill, New York on January 1, 1916 as part of the foreword for his soon-to-be published book, A Book Lovers Holiday in the Open. The last chapter in that book, “A Curious Experience,” described a Quebec moose hunt that almost ended very badly a few months earlier.

The hunt was still fresh on his mind and for good reason. Roosevelt and his two guides had been attacked by a rogue bull moose, and he had been forced to shoot the enraged animal at a distance of only 20 feet. Although the incident left an indelible imprint on his psyche, little could he know at the time this was to be the last big game animal on which he would ever squeeze the trigger.

Always the adventurer, Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) had traveled to the wilds of South America a few years earlier in 1912 to obtain specimens for the Smithsonian Museum just as he had on his historic, one-year African odyssey back in 1909. Having been recently defeated by Woodrow Wilson in a bitter presidential campaign, South America seemed just the place to lick his wounds. The trip proved to be an overwhelming success as far as collecting material for the museum was concerned, but it was also grueling and dangerous. Roosevelt contracted a fever in the jungles of Brazil that nearly killed him. For a man who had seemingly been invincible to assassin’s bullets and charging lions, the illness took its toll. He never fully recovered.

By 1915, TR had indeed reached a pinnacle in his life through many years of fast-paced living. He possessed the energy of at least three normal men and he had achieved countless accomplishments. He had looked death in the eye on San Juan Hill, faced dangerous animals in Africa and attained the highest office in the land. He had brought in the new century with a long list of unprecedented achievements, including being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The 57-year-old “Bull Moose” jumped on a train in New York City and headed to the wilds of Quebec for “a fortnight” of moose and caribou hunting.

In July, after giving a major political speech and seeing his youngest son off to college, the 57-year-old “Bull Moose” jumped on a train in New York City and headed to the wilds of Quebec for “a fortnight” of moose and caribou hunting. His worn-out old body might have been beginning to tire a bit, but his attitude was full steam ahead.

Roosevelt was thrilled to have been invited to hunt on the well-known Tourilli fish and Game Club property with his good friend and companion of many previous hunts, Dr. Alexander Lambert. Composed primarily of wealthy American and Canadian sportsmen, the Tourilli Club then boasted some 250,000 square miles of prime hunting and fishing territory leased from the government in Quebec Province. The club, incidentally, still thrives today.

Roosevelt arrived in Quebec and obtained a license to shoot one bull moose and two caribou of either sex. TR and Lambert spent two weeks in early September hunting moose and caribou. They dined on moose meat provided by the good doctor. Because caribou numbers had declined in the area, it was decided no cows were to be shot. At that time, only a small, remnant population of caribou still existed in southern Quebec. Most had been killed out during the previous decades by excessive market hunting. According to Roosevelt’s guides, wolves had made a recent comeback to the area and they were also impacting the few remaining caribou.

Roosevelt arrived in Quebec and obtained a license to shoot one bull moose and two caribou of either sex. Because caribou numbers had declined in the area, it was decided no cows were to be shot.

TR and Dr. Lambert stayed in a cabin on a picturesque lake in the Ste. Anne River country 30 miles northwest of Quebec City. A series of alluring finger-lakes were connected by short, overland portages and Roosevelt was anxious to do some exploring.

On the first day out, Roosevelt saw a caribou cow and two calves. A day or two later he set out with two strapping young French Canadian guides, Arthur Lirette and Odilon Genest, for a small, remote cabin where Lambert had once stayed on one of the distant lakes. After they settled in camp, TR killed a small caribou bull for meat.

The men usually hunted from canoes, paddling around the lake and scouting the edges for feeding game. On the morning of September 19, 1915, Roosevelt was out with his guides when he shot an outstanding bull moose with antlers measuring 52 inches. Most of the midday hours were spent skinning, caping and butchering the meat for transport.

By mid-afternoon, the men neared the final portage area where they would carry the canoe across a small section of land to an adjoining waterway that led back to Lambert’s cabin. Just as they were about to beach their canoe, a second bull moose suddenly appeared out of nowhere. Roosevelt described it as being much larger in body size than the bull he had killed earlier. Judging by its odd behavior, he believed it to be an older animal that had never before seen a human.

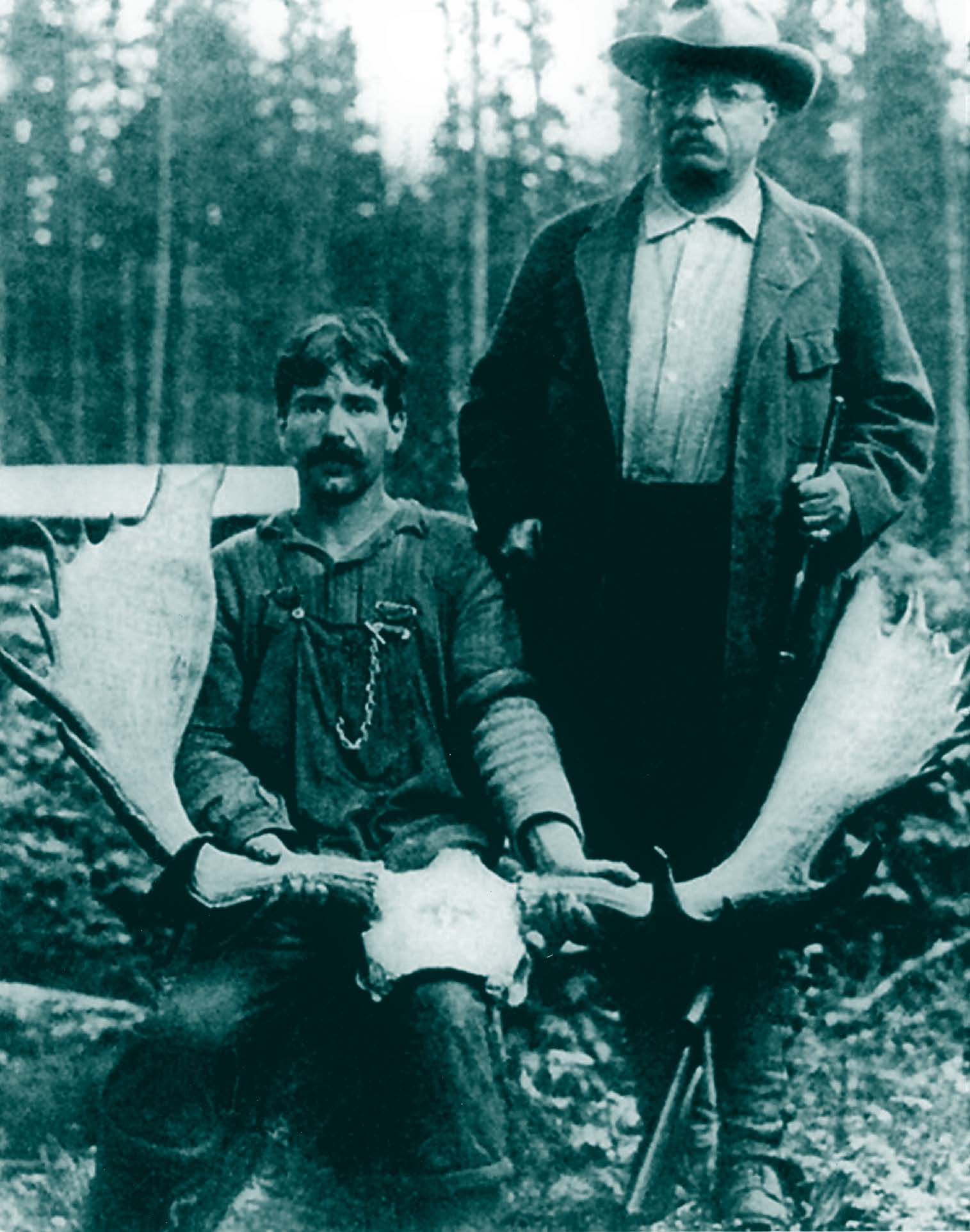

Theodore Roosevelt and his guide, Arthur Lirette, pose with the antlers of the moose that TR shot at point-blank range with his trusty Springfield .30-06 during his 1915 hunt in Quebec. Although TR gave away most of his big game trophies to friends, family and museums, he kept this rack as a reminder of his hair-raising experience with a very belligerent bull moose. The rack has resided at Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, New York for more than 100 years.

As they approached the shore, the moose became very agitated and aggressive with “hair bristled.” The three men made noise, pounded on the side of the canoe, and paddled up and down the lake for at least an hour as the bull followed their every move and made threatening advances whenever they neared the shoreline.

By late afternoon, the moose finally melted into the bush, and it seemed as though the coast was clear. The men quickly landed the canoe and started portaging across to the other waterway. Suddenly, as they neared a small stream, the moose appeared out of nowhere and charged. Roosevelt described the chilling event in the last chapter of A Book Lovers Holiday in the Open.

“After about ten minutes, the trail approached the little stream; then the moose suddenly appeared, rushing towards us at a slashing trot, its hair ruffled and tossing his head. Arthur Lirette, who is one of the game wardens of the Tourilli Club [as well as one of Roosevelt’s guides], called out to me to shoot, or the moose would do us mischief. In a last effort to frighten it, I fired over its head, but it paid no heed to this and rushed the stream at us.

“Arthur again called ‘Tirez [shoot], monsieur, tirez, vite, vite, vite’, and I fired into the moose’s chest, when he was less than twenty feet away, coming full tilt at us, grunting, shaking his head, his ears back and his hair brindled; the shot stopped him; I fired into him again; both shots were fatal; he recrossed the little stream and fell to a third shot; but when we approached, he rose grunting and started towards us. I killed him. If I had not stopped him, he would certainly have killed one or more of our party; and at twenty feet I had to shoot as straight as I knew how or he would have reached us.”

Roosevelt had been hunting with his trusty Springfield .30-’06 bolt action. Since he technically had broken the law by shooting a second moose for which he had no license, he filed an affidavit with the proper authorities in Quebec describing the incident so he could clear his name. In part the affidavit read:

“If I had not stopped him (the moose), he would certainly have killed one or more of our party. I had done everything possible in my power to scare him away for an hour and a quarter, and I solemnly declare that I killed him only when it was imperatively necessary, in order to prevent the loss of one or more of our own lives, and I make this solemn declaration conscientiously, believing it to be true, and knowing that it is of the same force and effect as if made under oath, and by virtue of the Canada Evidence Act 1893.”

Roosevelt was cleared of any wrongdoing and given possession of the rack. The incident had shaken him to the core, and he told several friends he hoped nothing like that ever happened again. Sadly, his health began failing shortly after the Quebec hunt.

Three years later, in July, 1918, as World War I raged in Europe, Roosevelt was informed that his youngest son Quentin had been killed in combat in Europe. The news was crippling. Some said the old war horse lost his will to live.

On Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, Roosevelt was rushed to a New York hospital where he spent six weeks trying to regain his strength. He was allowed to go home in late December for the holidays. Two weeks later, on January 6, 1919, after working on a magazine article about postwar reform regarding the conservation movement in America, he went to sleep and never woke up.

Roosevelt’s historic home at Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, New York.

Roosevelt cut his big-game-hunting teeth on whitetails and mule deer in South Dakota where he purchased a ranch in the mid-1880s. Totally distraught over an earlier loss—the sudden deaths of his first wife and his mother within a 24-hour period (his wife had died shortly after giving birth to a daughter in 1884 and his mother had died in the same house the very day before), he left his baby daughter to be cared for by his sister and headed west. It was the best therapy he could have chosen.

For the next few years, TR was in his element, living the “strenuous life” outdoors he so deeply treasured as an adult. Several years of ranching and hunting at every opportunity reinvigorated him as nothing else could. Although he eventually hunted grizzlies and most other big game species in the West, and later pursued other dangerous game in Africa and South America, he always had a special place in his heart for whitetails—the deer he liked to call “the little deer of the river bottoms.”

Roosevelt on his horse, Tranquility, during his year-long safari in Africa. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF ANDRÉ BEAUDRY

After Roosevelt returned to New York from his life-changing exile in the Dakotas, his fast-paced political career took off and never slowed down. Among numerous other achievements, he became the nation’s 25th president, he won the Nobel Peace Prize, he founded the Boone and Crockett Club, and he became a driving force in the conservation movement of the early 1900s. By the end of his short, 60-year lifespan, he had written more than 30 books.

Roosevelt gave away the antlers and horns from most of his big game trophies to friends, relatives and the Smithsonian Museum. Even though the antlers from his rogue bull moose were never mounted, they hung on the wall in his study at Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay New York long after his death.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Included here are the experiences of Teddy Roosevelt in “The Wilderness Hunter,” of Jack O’Connor in “The Leopard,” of J. C. Rickhoff in “Wounded Lion in Kenya,” of Frank C. Hibben in “The Last Stand of a Wily Jaguar,” and of John “Pondoro” Taylor in “Buffalo,” among others.. Shop Now