With horse and rifle he explored frontiers, indulging a lust that would transcend politics.

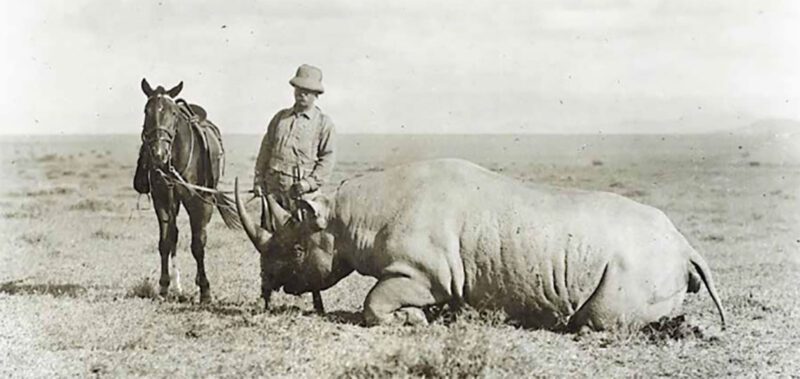

“Every sense keyed up…I pushed forward the safety of the double-barreled Holland rifle. As I stepped to one side [to aim], the rhino saw me and jumped to his feet with the agility of a polo pony…. I put in the right barrel, the bullet going through both lungs. At the same moment he wheeled, the blood spouting from his nostrils, and galloped full on us…. I struck him with my left-hand barrel, the bullet entering the neck and shoulder and piercing his heart.” – African Game Trails

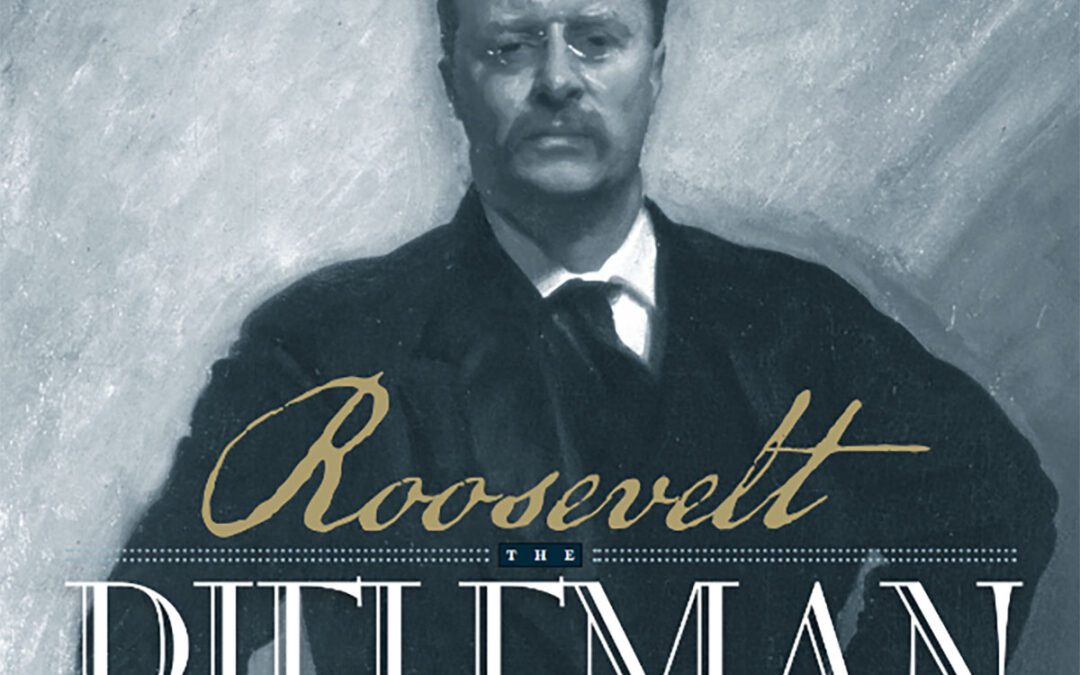

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. defined the bully pulpit, spared the teddy bear and led the strenuous life. “I do not believe,” he declared in a late retrospective, “that any president ever has had so thoroughly good a time as I have had….”

Theodore Roosevelt with Rhino – one of Kermit Roosevelt’s photographs of the African safari, 1909-1910

Born to privilege October 27, 1858, young Roosevelt had no given middle name. He endured the length of his first and last until a charitable soul eventually hailed him as T.R. Debilitating asthma struck the lad early on. He worked to build his body and condition it for the outdoors. Home schooling prepared him for later years at Harvard College.

During Roosevelt’s childhood, civil war rent the nation’s bonds and tested its resilience. Into this tumult came an arresting new firearm. “… Where is the military genius [to] modify the science of war as to best develop the capacities of this terrible engine, [which might] enable any government … to rule the world?” So Oliver Winchester urged the Army to adopt the 1860 Henry rifle, offspring of Walter Hunt’s 1848 Volitional Repeater.

The slim, lightweight ’94 was an instant hit in 30 WCF (30-30), our first smokeless round.

Hunt had sold early patent rights to George Arrowsmith. After ministrations by Lewis Jennings, the balky rifle went to Courtlandt Palmer, who asked Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson to bless it with a metallic cartridge. The three men formed a partnership in 1854. A year later, 40 investors bought them out to found the Volcanic Repeating Arms Co. Oliver Winchester became its director. When slow sales forced receivership in 1857, Winchester paid $40,000 for all assets and, under the fresh banner of the New Haven Arms Co., hired Benjamin Tyler Henry to refine the Hunt repeater.

Though few Henry rifles were issued, their 15-shot capacity got the attention of Confederates. By 1866, New Haven Arms was Winchester Repeating Arms. Its sequel to the Henry: the Winchester 1866. A side loading gate made the ’66 easier to load. Its magazine was sturdier and enclosed by a wooden forend. As on the Henry, the firing pin had two prongs to strike both sides of the .44 rimfire cartridge. A new load fired a lighter 200-grain bullet from a frothier 28-grain powder charge.

Between 1883 and 1900, firearms genius John Browning developed Winchester’s top-selling hunting rifles.

Firearms would dominate headlines during the 1870s, as a tide of wrecked lives broke over the harsh, lawless landscapes of the West. Clinically called expansion, its destiny was anything but manifest.

The Earp-Clanton brawl at Tombstone’s OK Corral in 1873 was more the climax of a feud than law enforcement. Remarkably, for all its celebrity, this 30-shot firestorm claimed just three of the eight antagonists, at ranges reportedly averaging 6 feet!

George Custer’s troops suffered heavier casualties on the Little Bighorn in 1876 – a truly lethal year. William Butler Hickok was shot in the back of the head at a Deadwood card table by Jack McCall. The James-Younger gang was minced by citizen gunfire during a bank holdup in Northfield, Minnesota.

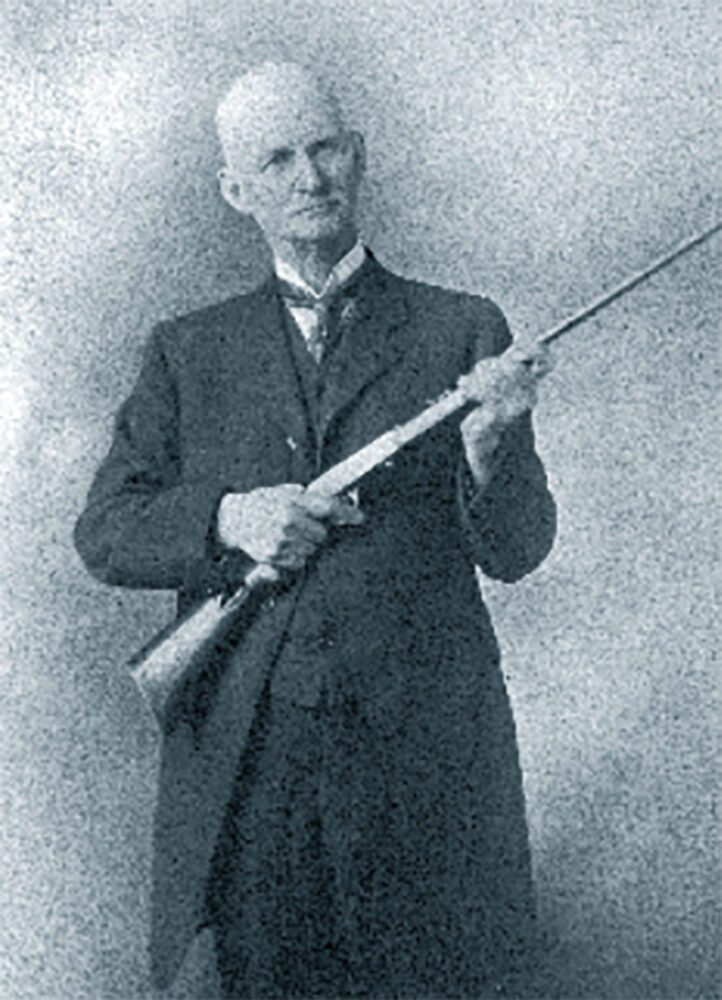

About then a young Tom Horn was drifting west from his home in Missouri. His path would later cross T.R.’s in Cuba, where Horn served as a packer for the Rough Riders. Work as a livestock detective later proved his undoing. In 1903 he was convicted of killing 14-year-old Willie Nickell and hanged, age 43.

Not all was violence. By 1876 Phoebe Ann Moses had beaten Frank Butler in a rifle match. The Ohio girl was 15 when they married, then joined his traveling show. As Annie Oakley she earned a place in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, where she shot coins from Frank’s fingers and aimed in a mirror to shatter glass balls he tossed. Her eye-popping routines and sweet demeanor endeared her to audiences. Johnny Baker, another pro, tried for 17 years to outshoot Annie, “She wouldn’t throw a match,” he said. “You had to beat her. And she just wasn’t beatable!”

After the 1903 Springfield replaced the Krag, the 30-40 gave way toe the 30-06 in both infantry and sporting rifles.

Winchester, meanwhile, had introduced two new rifles. Its Model 1873 was an improved 1866, iron then steel replacing the brass receiver and a carrier cover shielding the action from dust, rain and snow. The 1873 chambered Winchester’s first centerfire round. The 44-40’s 40 grains of blackpowder hurled a 200-grain bullet at 1,200 fps. In 1875 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody effused: “… For general hunting or Indian fighting I pronounce your improved Winchester [1873] the boss….” The 1873 was later bored to 38-40 (38 WCF, in 1880) and 32-20 (32 WCF, in 1882). Beginning in 1884, the mechanism was modified to cycle 22 Rimfire ammo. Hailed for its part in settling our West, the ’73 traveled abroad, helping militias mold nations. The last of 720,610 of these rifles shipped in 1924.

Winchester’s Model 1876, of similar design, had a bigger mechanism to handle such cartridges as the 45-60, introduced in 1879. Tom Horn may have used this mid-length round, with 300-grain bullets at 1,315 fps. Friskier than the 44-40, it still fell shy of matching the loads of “buffalo rifles” – Remington’s Rolling Block and the 1874 dropping-block Sharps.

Roosevelt favored the saddle-friendly model 1894, his “little 30,” for all-around hunting in the West.

During the post-war decade that coaxed T.R. from his native New York, cigar-size cartridges in those single-shots – and the Army’s 1873 “Trapdoor” Springfield – purged the plains of bison. “Brazos” Bob McRae claimed his Malcolm-scoped 44-90 Remington took 54 of the beasts with as many shots from one stand. After an 1873 hunt with a Rolling Block, George Custer noted: “I killed far more game than any other single party…at longer range.” As the price of buffalo hides climbed to $50, ambitious hunters could earn $10,000 a year. A Rolling Block rifle cost $8. With Sharps 1874s, Rolling Block 44-90 match rifles designed by Remington’s L.L. Hepburn beat a swaggering Irish team in much-heralded competition at 800, 900 and 1,000 yards on Creed’s Farm, Long Island, September, 1874.

Christian Sharps would die of tuberculosis before his rifles played their starring role in the West. The New Model 1869 was the first for metallic cartridges, preceding the New Model 1874 that defined the brand for 12 years after its 1870 debut. The .50 made legend by buffalo hunters burned 100 grains of blackpowder in a 2 1/2-inch case, behind a 473-grain paper-patched bullet. Sharps did itself no favor with its proprietary cartridges (six .40s, three .44s, four .45s, three .50s).

By 1878, Colt and Winchester were producing revolvers and rifles in 44-40; Army rifles and carbines fired the 45-70. Plains Indians coveted those arms for their ubiquitous ammo. A Sharps appealed only if ammunition was found with it. Besides, the utility of these cartridges had diminished. By the mid-’80s, so many buffalo had been shot that human scavengers would glean 3,000,000 tons of bones from the fly-blown prairie. The Sharps Long-Range Model 1877, a bargain at $100, faced a tide of reliable lever-actions selling for as little as $11.

The artist’s rendering shows Winchester’s competition: the Remington Rolling Block rifle.

Roosevelt and other hunters in the late 1800s preferred repeaters, and Winchester owned that part of the market. Credit John Browning. For 17 years after Winchester President (and Oliver’s son-in-law) Thomas Bennett bought rights to a Browning rifle that appeared as Winchester’s Model 1885, he kept the Utah genius busy. Winchester bought 44 Browning designs, shelving those it did not intend to produce to keep them from the competition. Models 1886, 1892, 1894 and 1895 lever rifles were Browning designs.

“The Winchester,” T.R. would write, “stocked and sighted to suit myself, is by all odds the best weapon I ever had, and I now use it almost exclusively, having killed every kind of game with it…. [It] is deadly, accurate and handy…stands very rough usage and is unapproachable for the rapidity of its fire.”

Model numbers seemed immaterial to many of the faithful then writing about their favorite lever rifles. Even after the turn of the century, “Winchester” was descriptor enough!

First rifle! T.R. owned several Model 1876s, big but relatively weak and short-lived repeaters.

Roosevelt bought two 1876s in 50-95 when he was 22. A trip to Dakota Territory fueled his zest for the outdoor life. Arriving in clothes that by his later admission made him out a “cowboy dandy,” he impressed the ranchers whose skills and resourcefulness he admired. His enthusiasm was infectious; he threw himself into hard work with gusto. And he killed his first buffalo – oddly enough with a Sharps in 45-90. Enamored of frontier life, Roosevelt invested in the Maltese Cross Ranch.

His return to New York was attended by tragedy. On a single day in February 1884, T.R. lost his mother to typhoid and his wife Alice to Bright’s disease. She had just given birth to a daughter. Grieving, the young man sought solace on his Dakota property and increased his stake with the Elkhorn Ranch.

In 1886, weather tested his resolve. A blizzard of historic ferocity ravaged the northern plains, killing up to 90 percent of its livestock. Roosevelt’s wealth sheltered him, but many cattlemen lost their struggle for a life already imperiled by fences and feedlots.

T.R. had famously poor eyesight and freely admitted he was a mediocre marksman. He favored lever-action rifles mainly because they could be cycled from the shoulder. “I don’t shoot well, but I shoot often!” He liked costly indulgences, ordering engraved, case-colored receivers and half-octagonal barrels, fancy walnut stocks with crescent cheek-pieces and pistol-grip wrists. Half-magazines, shotgun butts and Freund sights caught his fancy. Roosevelt enjoyed the company of other rifle enthusiasts, even those who gave Winchesters and fencing pliers the same maintenance. He presented one of his elegant Model 1876s to his Dakota hunting guide and ranch manager William Merrifield.

Next on T.R.’s shopping list was a Model 1873 in 32-20 and another’76, in 45-75. At the time there were few options in repeaters. But that was about to change.

Winchester’s 1892: essentially a short-action ’86. More than a million would ship before the last in 1941. Roosevelt’s first was evidently in 32-20.

Winchester’s 1876 lasted just a decade. Its weight and bulk belied genetic weaknesses. Asked by Bennett to come up with a better rifle, John Browning applied the vertical locking lugs he had designed into the rifle that was now Winchester’s Model 1885. Even before the company had that single-shot into full production, Browning delivered a superb lever-action that would handle bigger cartridges and higher pressures. He earned $50,000 for the Winchester Model 1886 – “more money than there was in Ogden.” Roosevelt used it afield and liked it immensely. Bennett immediately put Browning to work on a short-action version. The Utahn dismissed a two-month deadline, hiked the price and told his New Haven boss, “I’ll have it to you in 30 days, or it’s free.” Incredulous, Bennett agreed. Browning came through early.

Available in 44-40, 38-40, 32-20 or 25-20, Winchester’s Model 1892 held up to 17 rounds and weighed as little as 5 1/2 pounds. More than a million would ship before the last in 1941. The Model 1894 came on its heels. It fired mid-length cartridges, notably the 30 WCF, or 30-30, our first smokeless hunting round. At its debut, the 1894 sold for $19.50. Tom Horn was carrying one when arrested for the Nickell slaying. Theodore Roosevelt would count a ’94 in 30-30 among his favorite Winchesters, calling it his “little 30” and keeping it on his saddle for western hunts. He fitted another ’94 with a Maxim silencer for home use at Sagamore Hill.

T.R. used a Springfield in 30-06 like this one on his 1909-1910 safari, reporting kills at more than 300 yards.

T.R.’s public service career began with his election to New York’s State Assembly and various appointments that followed. At war’s onset in 1898, he organized the 1st Volunteer Cavalry. A charge up Kettle Hill during the Battle of Santiago brought Roosevelt and his Rough Riders wide acclaim. That year he won the race for Governor of New York. But his personality didn’t please the Republican machine. Its plan to shelve him in the office of Vice President failed short months after the election of 1900.

On September 14, 1901, President William McKinley succumbed to a bullet from anarchist Leon Czolgosz. At 42, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. became the youngest President of the United States.

While that post demanded much of him, it didn’t diminish his affinity for rifles or hunting. T.R.’s energy dominated the White House and impressed outdoorsmen. One of these was Holt Collier. Born into slavery, Collier served from age 14 as the Confederacy’s only black soldier from his native Mississippi. After the war, he worked as a dog handler. On a 1902 hunt with the President, he roped then tugged to shore a bear that had sought refuge in a lake. Roosevelt refused to kill it. Cliff Berryman put “Teddy’s bear” in a Washington Post cartoon. The toy industry responded.

Five years later in Louisiana, the President got another chance. Again Collier handled the hounds. “Mr. Clive,” he urged the hunt-master, “don’t put him on no stand. He ain’t no baby.” Roosevelt couldn’t have asked for higher praise. The bear he shot at 20 yards would be his last. T.R. thought a lot of Collier and presented him with a rifle (sources differ as to whether it was a Model 1894 or an 1886).

In 1907, during his full term as President, Roosevelt bought an NRA Life Membership for $25.

For heavy game, Kermit used big-bore Rigby rifle. (T.R.’s was a Holland & Holland 500/450.)

By then he’d adopted a new Winchester, the Model 1895. It differed dramatically from previous Browning-designed lever rifles. Instead of an under-barrel tube, the magazine was a box in the receiver’s belly. Vertically stacked instead of nose-to-primer, pointed bullets posed no hazard in recoil. They flew flatter and retained energy better than did flat-nose bullets mandated by tube magazines. Offered first in 303 British and 30-40 Krag, the 1895 later appeared in 30-06, and in 35 and 405 Winchester. Many in 7.62 Russian were sold to the Russian government. Roosevelt called his 405 his “big stick.” He’d rely on it often during the hunt of his lifetime.

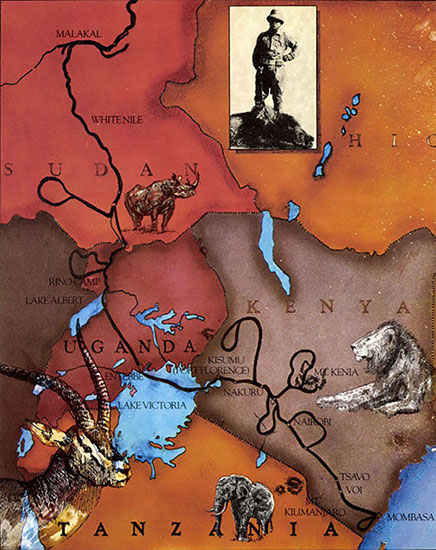

He began that safari March 23, 1909, less than three weeks after his friend and Secretary of War William Howard Taft assumed the Presidency. T.R. had served seven years. Despite his popularity, he’d declined to run again. “I am fond of politics,” he said, “but am fonder still of a little big game hunting.” With Roosevelt’s backing, Taft beat William Jennings Bryant in his third and final try for the oval office.

Roosevelt left the country with his 19-year-old son Kermit on the steamer Hamburg. At Naples they changed to the Admiral, under German registry. They reached British East Africa (now Kenya) at Mombasa, terminus for the Uganda railway. Newland & Tarlton handled the outfitting. Australian Leslie Tarlton would join the safari, with R.J. Cunninghame at its head. To fund the trip, Andrew Carnegie had matched T.R.’s own contribution of $25,000. Another $50,000 came from the Smithsonian Institution. Roosevelt was accompanied by three naturalists, one a taxidermist, as the safari was to collect specimens for the Smithsonian and the American Museum of Natural History.

The kit, carried off-rail by 250 porters, included powdered borax and four tons of salt for preserving hides. T.R. had also brought 60 pounds of books in a trunk – “my pigskin library,” plus 15 crates of rifles, ammunition and spare parts. He put “in each provision box a few cans of Boston baked beans, California peaches and tomatoes.”

By good account, the hunters’ battery comprised five Model 1895 Winchesters: a 30-06 and four in 405, one with a Maxim silencer. A Marlin 1893 was the only lever-action not a Winchester. T.R., who would eventually own at least 20 Winchesters, liked this rifle, a 25-36. He brought “an army Springfield” in 30-06 (“lightest and handiest of all my rifles”), a Holland & Holland double in 500/450 and a 12-bore Fox shotgun. In his African Game Trails he noted that Kermit packed a Rigby double rifle.

The group traveled northwest to the Belgian Congo (now the DRC), then to the Sudan, hunting on a 10-month trek. A keen observer, T.R. noted in detail the country and the cultures visited. This excerpt is from a Masai lion hunt:

For heavy game, Kermit used big-bore Rigby rifle. (T.R.’s was a Holland & Holland 500/450.)

“His mane bristled, his tail lashed, he held his head low, the upper lip…drawn up so as to show the gleam of the long fangs…. It was a wild sight; the ring of spearmen, intent, silent, bent on blood, and in the centre the great man-killing beast…. [He] looked quickly from side to side, saw where the line was thinnest and charged at topmost speed…. With shields held steady and quivering spears poised, the men in front braced [as] from either hand the warriors sprang forward to take their foe in flank. [The leader’s] long spear flickered and plunged…. [The lion] then flung himself on the man in front. The warrior threw his spear; it drove [shoulder to thigh], a yard of steel through the great body. Rearing, the lion struck the man, bearing down the shield, his back arched, [slaking] his fury with fang and talon. But on the instant I saw another spear driven clear through his body…blades darting toward him were flashes of white flame…. As he fell he gripped a spear-head in his jaws with such tremendous force that he bent it double.”

Roosevelt told the two injured men he’d give each a heifer. “A Nandi prizes his cattle rather more than his wives; and each sufferer smiled broadly at the news.”

T.R. reported in detail, with candor but also the eye and interests of a rifleman: “I killed a topi bull at 260 yards with one bullet and a wildebeest bull with a dozen; I crippled him with my first shot at 360 yards….”

Another time, “Tarlton, whose eye for distance was good, told me the hyena was over 300 yards off [so] I put up the 300-yard sight and drew a rather coarse bead; and down went the hyena [at] just over 350 long paces.”

Again: “I had the little Springfield, and was anxious to test the new sharp-pointed military bullet on some large animal. [A big eland] was facing me just 280 yards off…. The tiny ball broke his back.” A following shot killed the second bull of the pair.

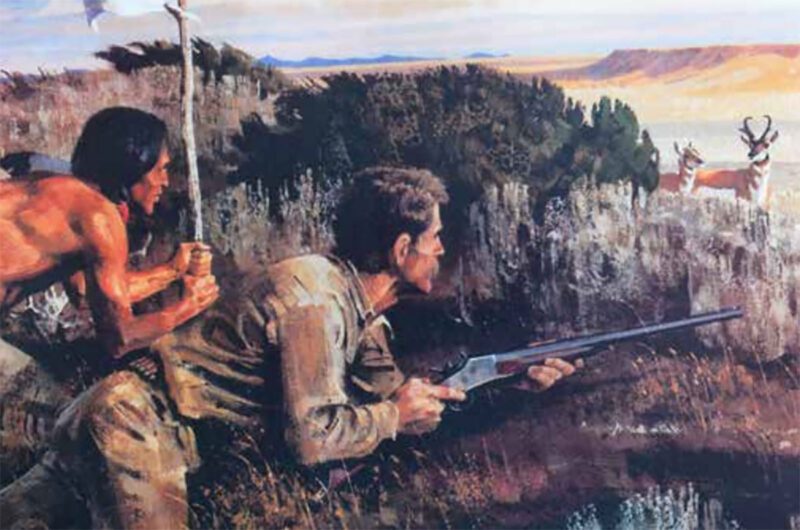

Buffalo Rising (detail) by John Seerey-Lester

Even when excitement ran high, Roosevelt showed the analytical bent of the true rifle enthusiast.

“… We kept the Winchester bullets both from Kermit’s giraffe and from mine. I made a point of keeping as many as possible of the bullets…to see just what was done by the different types of rifles….”

Retrieving 405 Winchester solids from a rhino carcass, T.R. found they had “mortally wounded” the beast but “inflicted no such smashing blow as the heavy bullets of the Holland, [tending] to break into fragments, while the big Holland bullets ploughed through.”

Theodore Roosevelt, Leslie Tarleton and R.J. Cuninghame (on elephant), with dead elephant in Meru, Kenya.

Like many hunters, T.R. found elephant hunting a powerful experience: “The cover was so high that we could not see their tusks, only the tops of their heads…. I fired when [the biggest] was 60 yards away. [Missing the brain, the bullet] brought the elephant to its knees; as it rose I floored it with the second barrel….”

T.R. reloaded and fired twice at the next animal. It fell, but the first rose. He gave it both barrels; however, the “brain is not an easy mark…. I snatched up the little Springfield rifle and this time shot true….” The first elephant got up and escaped.

Another time: “A few more steps gave Kermit a chance at its head, at about 60 yards, and with a bullet from his 405 Winchester he floored the mighty beast. It rose, and we both fired in unison, bringing it down again; but as we came up it struggled [to rise; so again] we both fired together. This finished it.”

Roosevelt’s summations are almost clinical in their candor. Never one to downplay the violence and risks of “the arena,” he told frankly of ragged killing. In that day, it was broadly accepted.

“My bag for five days included 14 animals….. The average distance at which they were shot was a little over 220 yards. I used 65 cartridges…. One wounded animal got away…. Many of the cartridges expended really represented range-finding.”

T.R. recorded only one rifle failure: “Stalking as close as he dared, [Kermit] fired three shots [into the eland].” He saw it was a cow as the much bigger bull appeared. He downed it. It rose. He struggled to eject the spent hull over the 1895’s now-empty magazine.

In safari gear of the day, with a pose also then in fashion, Roosevelt stands over a fine lion shot with his Winchester 1895 in 405, a rifle he considered ideal for hunting big cats.

“The faithful Winchester, which Kermit had used steadily for 10 months…which had suffered every kind of hard treatment and had killed every kind of game, without once failing, had at last given way….” The bull recovered and made off as Kermit at last filled the magazine. He followed “a mile or two,” hit it twice with four shots as it got up. Hundreds of yards on, he killed it with his last bullet.

As much as he thrilled to the shot, T.R. kept in mind the safari was for others as well. He took no kudu, bongo or sable – though Kermit killed at least two each of these coveted antelopes. Of the 11,397 animals recorded on the trip, fewer than 5,000 were mammals. Only 61 were of the “big five.” The 4,000 birds, 2,000 reptiles and amphibians and 500 fish would make cataloging an eight-year project.

Roosevelt the Rifleman

The Roosevelts returned early in 1910. A few months later, T.R. was ready for another adventure. Denied the Republican ticket by the party for the 1912 presidential race, he ran as a “Bull Moose.” The split in Republican ranks threw the election to Woodrow Wilson.

Ever one for the wilderness, T.R. chose a trip down South America’s River of Doubt as his next bite of the strenuous life. It almost finished him. Arguably the Republicans’ Presidential hope for 1920, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. died of a pulmonary embolism at his Oyster Bay home early in 1919. He was 60.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2020 Nov./Dec. issue of Sporting Classics.

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now