Forget the business of slams; it was simple wanderlust, the desire to experience anything foreign and untried that placed bow-hunting Roosevelt elk at the top of my wish list for so many years.

I’d long contemplated driving westward from my home in New Mexico to bowhunt Oregon’s public lands on my own, but reliable intel had proven elusive. Booking a guided hunt to help tip the odds in my favor had remained a financial impossibility.

In time, I met bowhunters who lived in Roosevelt elk country and had experienced some amount of success. Hunt trades were discussed—my success with Coues whitetails always a solid bargaining chip. Several plans were even set in motion, but one thing or another always dashed those hoped-for adventures.

The false starts only made me more determined, elevating the Roosevelt elk to the very top of my bucket list. I’d also adjusted to the notion that the financial end was not as hopeless as it once had seemed, so for the first time in my life I called a reputable booking agent for assistance. This brought southwestern Oregon’s Ken Wilson, owner of Spoon Creek Outfitters, into my life, giving me hope, or more accurately, cock-sure confidence.

The year before, Ken had posted nearly 100 percent shooting opportunity for his clients. Nearly 50 percent of those shots resulted in filled tags, with a good number of those tagged bulls making book.

I had guided New Mexico elk hunters for something like 23 years. I’d taken a couple dozen archery bulls myself, three of those bettering 365 inches. I had literally written the book on the subject: Bowhunting Modern Elk, a book indorsed by none other than Mr. Elk himself, Larry D. Jones. I thought I knew a thing or two about elk hunting. My problem, it seemed, was solved.

Only if you believe in fairy dust and unicorns . . .

This much I knew about Roosevelt elk: They were found only in the steep, wet coastal ranges of the Pacific North-west. This encompasses habitat from northwestern California (where tags are tightly controlled) through extreme western Oregon and Washington (where over-the-counter tags are available, but the hunting pressure on public lands is intense), and north to British Columbia’s Vancouver Island (where the biggest bulls are found, but limited tags had boosted the price of admission from 17 to 25 grand).

All of these challenging rainforest environments are characterized by limited visibility and (typically) non-stop rain. In other words, drastically different conditions than those used in the arid mountains of western New Mexico’s Gila region.

On average, Roosevelt elk sport much smaller antlers than their Rocky Mountain cousins, though the very largest bulls can score in the 350s to 360s. The biggest Rocky Mountain bulls can score 40 to 50 inches more. And while 225 inches of Roosevelt antlers can get your name into archery record books, 260 inches are required to enter Rocky Mountain elk.

Roosevelt elk make up for their smaller antlers with a notably larger body mass, a combination of lush feed and mild winters that enable them reach 1,000 pounds or more.

The hunting details for Roosevelt elk remained blurry, washed in half-baked myth and hearsay. I would ultimately find that many of my assumptions were completely false—and especially that hunting Rocky Mountain elk had taught me nothing useful to employ in Roosevelt country.

It was the third week of September when I arrived at Ken’s, perfectly timed to take advantage of the rut. Through some sort of miscommunication, I’d arrived a day and a half early. Ken’s top guide had planned to take me out, but he was still occupied with other clients, which meant things weren’t going well. I wasn’t overly concerned, though. In fact I was more than happy to hunt on my own until my guide had shaken free. After all, I was in prime elk country, pre-scouted by Roosevelt elk gurus. And I was supposed to know what I was doing, right?

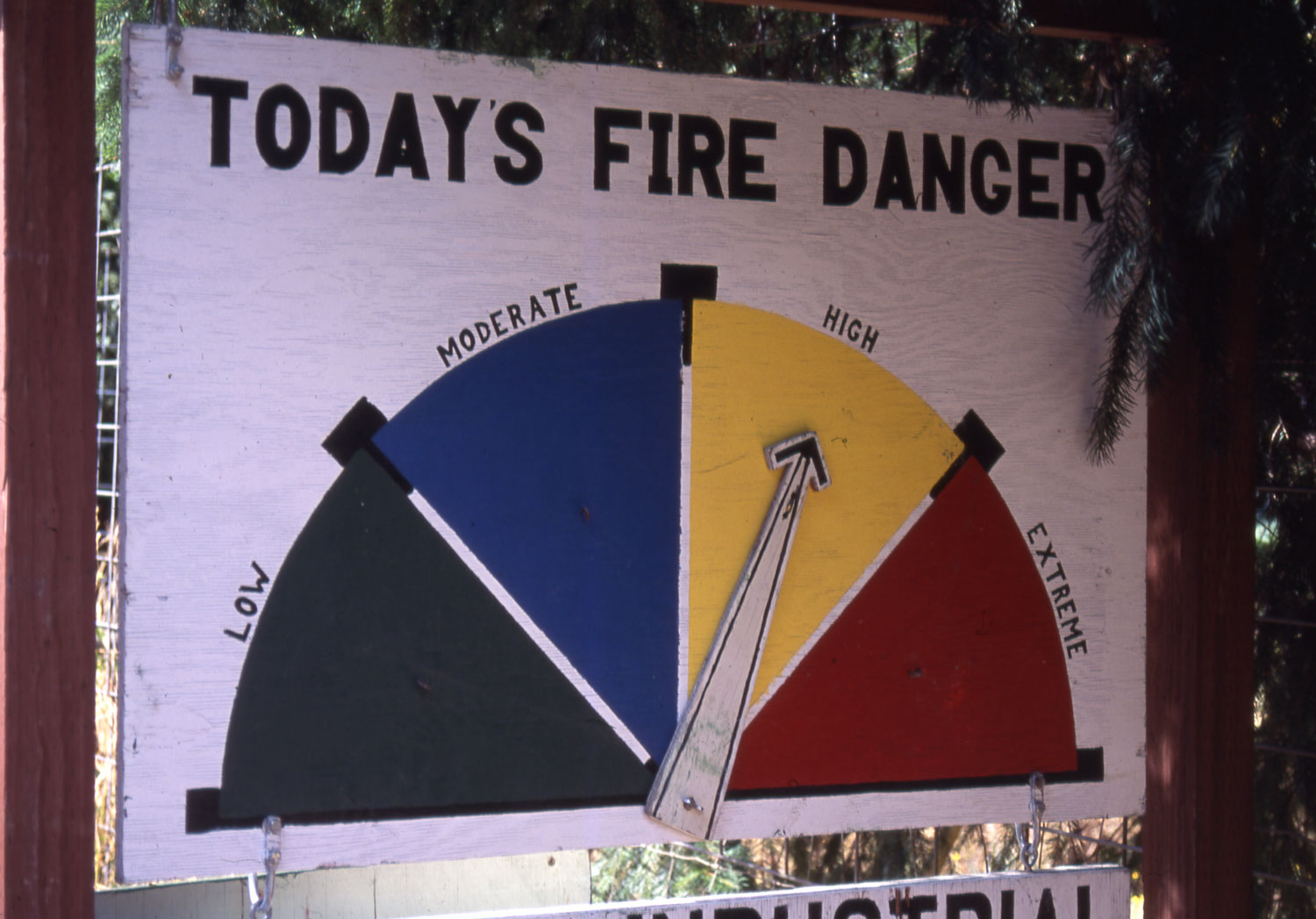

The greater apprehension arrived via a discouraging hunting report: After a couple weeks of concerted effort, no one had killed an elk. It was extremely dry, half the country closed due to fire danger, and many of Ken’s leased timber properties were suddenly off limits. If it didn’t rain to cool things off and quiet the woods, it would mark the worst hunting in years.

In the dark of my first morning, I parked at an inconspicuous roadside pullout. Ken’s directions were explicit, if also lacking a certain bit of detail: Stalk the defunct logging skid slowly and quietly, pausing at various cuts to bugle into the black forest. I’d reach a reseeded area where a nice five-by-five had been seen during summer scouting.

As light oozed across the land, I slipped down the logging road and begun to grasp just what I was in for. I was quickly swallowed by dark, enveloping forest. Forest isn’t really an apt term—it was a rainforest jungle! I had anticipated finding an opening where I might plant myself to glass, but the forest only grew more thronged as I proceeded. I was receiving a crash course in the claustrophobic pretexts of bowhunting Roosevelt elk.

Deeply cut trails showed recent sign, including still-wet splashes of urine. I pointed a bugling tube into the dark forest, cringed, and produced a squealing bugle. The cringe was involuntary, earned after years of bowhunting call-shy New Mexico bulls. Bugling, even cow-calling, had become a sure way to literally blow your hunt back home, something also true in many other Western elk states. I was only following instructions.

This calling business was perhaps the biggest surprise. It had been my impression that Roosevelt elk simply weren’t that talkative; indeed, that they hardly called at all. Long conversations with Ken had revealed that quite the opposite was true. In fact, calling was how most Oregon elk were tagged.

It is the nature of the habitat that has likely created this long-held myth. In these swallowing Coast Range confines, hearing elk talk is simply less likely because their bugles are instantly absorbed by the dense vegetation. The bigger news was that even the largest bulls in Roosevelt country respond to calls, even bugles. In fact, if it weren’t for this fact, few would be tagged at all.

My own bugle elicited no response, so I carried on, emerging into open clearcut littered with smoking-hot elk sign with several prime morning hours remaining. With no answers to my continued bugling, I plunged into nasty-thick forest, following distinct game trails, creating as much clamor as a herd of driven cattle. The forest was as dry as kindling.

It turned into an interesting morning, crashing blindly through that impenetrable cover, following trails that quickly vanished into tangles of thorny blackberry brambles while playing my bugle to a seemingly empty theater. All this was completely unfamiliar to me, and I had to admit, I really did need a guide to show me the way.

Senior guide Ross Morris shook his head knowingly while I related my morning’s frustrations. He reminded me yet again this was not Rocky Mountain elk hunting. Only after a couple days under his tutelage would I fully understand the gist of his words.

Bowhunting Roosevelt elk isn’t the physical dodge I had attempted to make it. It’s more like a game of chess—covering ground, yes, but doing so smartly while anticipating the animals’ moves. Most importantly, you don’t go to the elk; they must come to you. In these dry conditions, and especially in that jungle-like, second-growth cover, going to them was essentially fruitless. It was a complete reversal of everything New Mexico had taught me.

And then, I did succeed in coaxing a bull to me, only to find I was still a world away from success.

I got the bull going after spying a cow many hundreds of yards away at the edge of cover in another of Ken’s scouted hotspots. After closing the distance, I produced a subtle bugle and a bull responded immediately. Slowly I began mixing squealing bugles with cow calls, feigning a traveling herd. The bull seemed to be buying it.

The elk closed the gap quickly. Enthusiastic cow and calf chirps arrived on the wind, and I discerned breaking limbs and thudding, excited hooves. They were just over a lip of pushed earth at the edge of the clearcut. They couldn’t have been more than 40 yards away, but I could see no part of them.

Then I blew it, becoming impatient and more insistent with my calls. The forest grew conspicuously silent. I circled and got the bull going again, but light was draining away quickly. Again, breaking branches, excited cows, but no telltale tan blobs. And then it was dark and with it my vain aspirations of impressing the experts.

Come morning I had Ross to guide me. We traveled a labyrinthine of logging roads, parking well back from landings or inconspicuous road bends, stalking the edges to bugle into clearcuts. We trekked various logging skids, bugling at odd intervals, but turned back when those skids abruptly ended. Ross knew of secret, fern-blanketed benches that traditionally harbored elk. In these cases, we fought brush a half-mile or more, choking on floating fern dust, emerging to produce a couple bugles that fell on seemingly deaf ears.

It became apparent that the Roosevelt elk’s demeanor more closely mirrored that of white-tailed deer than nomadic Rocky Mountain elk. Fresh sign was everywhere, but the animals remained invisible.

We were bowhunting on faith gained through earlier scouting. During the summer months, Ken and Ross had spent endless hours locating elk concentrations, and particular bulls, glassing open clearcuts, attempting to establish patterns, determining if new logging activity had created or destroyed hotspots.

In short, it was the kind of scouting that holds little reward while bowhunting Rocky Mountain elk because they seldom camp out on a single swatch of ground for very long. But it’s effective for Roosevelt elk, because they are less inclined to wander. Even with hunting pressure they are more apt to hunker down rather than seek greener pastures. For this reason alone, we concentrated our efforts on just a few locations, nearly to the point of tedium.

We spent more time in the truck than hiking. For the hunter used to stretching his legs, it became somewhat monotonous, even maddening. This was not the physical game of bowhunting elk back home, where even a blank hunt offers a rewarding hike in the mountains. This hunt was more mental in nature.

During four days of hunting, we had discovered just one bugling bull, who was completely uninterested in our calls. We approached seven or eight cows and a single spike in three separate encounters. At home I might average six to eight encounters for every shooting opportunity, making bowhunting success a game of numbers. In Oregon we weren’t racking up anything close to such figures—due entirely to the weather, or more accurately, lack thereof. The odds had begun to appear very long of returning home with a Roosevelt bull.

Late on the previous afternoon, Ross had tossed a bugle into a familiar canyon head near where I had hunted alone that first day. It came as quite a shock when a bull bugled belligerently in retort. Ross tried him again with the same results.

“We’re in business,” he said, beaming, though darkness was descending quickly and the bull was well out of reach. “He’ll be here in the morning,” Ross assured, reading my mind.

To guarantee that sleep would prove impossible, the bull sent one last bugle ringing down the hollow before we retreated.

At first light we could make out distant tan forms through our binoculars, scattered across the grassy swamp. It was literally my last chance, and my inclination after so many desperate days was to bail off that mountainside like a starving coyote and to bushwhack through dog-hair-thick forest on a beeline toward the elk. Instead, we loaded up, turned the truck around and drove downhill atop blacktop. Ross knew of a relatively passable trail to the clear-cut our elk occupied.

Our bull was talkative, even his cows gossiping busily. As we slipped forward, a second bull joined in the festivities. We quickly set up on him, Ross fading back while I guarded a narrow cut at the swamp’s edge. The bull showed at 50 yards, a just-legal three-by-three. I wanted a Roosevelt badly, but I had glimpsed the herd bull and was gripped by sudden greed.

The small bull suddenly picked up our scent and ran straight into our herd, stirring up trouble. Remarkably, this actually saved us, as the larger bull apparently believed the small bull had arrived to challenge his right to the harem. It was time to get aggressive, something I’d learned from hunting Rocky Mountain. I moved forward in a quiet sprint.

The black-antlered five-by-five was marshalling a dozen or more cows, prodding them toward cover that would end the morning absolutely. I could see him through alder gaps, fervently rounding up reluctant laggards, bugling and panting through an open mouth.

I ducked into cover and rushed forward, taking advantage of the temporary chaos, the wind holding. The distance I popped with my laser rangefinder proved discouraging, but represented something I was certainly prepared for—something the open environments of New Mexico had helped hone to a razor’s edge.

As the bull paused between clumps of brush and fir, I snatched back the bowstring, placed the proper pin on his chest, and after carefully but hurriedly double-checking everything, allowed the string to slip off my fingers. My insides twisted as the bright fletchings arched in slow suspension. The arrow sliced into the bull’s ribs, and I began dancing spastically and pumping my fists—something I normally lambast while watching the rare episode of outdoor television. At that moment, I simply couldn’t help myself. Ross appeared, and I grabbed him in a bear hug, releasing all the frustrations of a mentally exhausting week.

My bull was dead just inside swallowing forest, and as we approached him, I was fully aware of how lucky I had been. The Roosevelt elk just might represent North America’s toughest archery trophy. The steep, jungle-like terrain is certainly part of this assertion, in addition to the secretive nature of animals that have evolved in such a dark and obscuring habitat. But I had also come to understand bowhunting Roosevelt elk requires as much mental toughness as Rocky Mountain elk require physical stamina.

No doubt about it; Roosevelt elk are different.