Think of the name Churchill and Churchill Downs might come to mind with mint juleps, outlandish women’s hats and sleek Arabian steeds or perhaps Winston Spencer Churchill who guided Britain through some of the darkest days of World War II. His quotes are many, but none strikes home more than, “Never was so much owed by so many to so few” when he spoke of the Royal Air Force who fought off the Nazi Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. But there is yet another Churchill: Robert Churchill, or “Bob” as his friends called him, who somewhat resembled Winston being stocky of frame, bald with a bit of the air of a bulldog about him: This Churchill is dear to shotgunners everywhere.

Robert Churchill inherited his uncle’s gunmaking company, E. J. Churchill, at age 24. Uncle Ted’s will read, “The business is to be carried on by my Nephew Robert Churchill whose wages are to be Raised to Three Pounds £3 per week.” The fact it was nearly bankrupt made his work all the harder to turn it into a success. Perhaps it was his other skill, that of a firearms scientist, that gave him the money to keep E. J. not merely afloat, but then turn it into a profitable gun-making company.

Not unlike Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, Robert Churchill was the real thing. He became an expert firearm witness in His or Her Majesty’s courts regarding the use of firearms in crimes. In the book, The Other Mr. Churchill, Churchill’s friend and biographer Macdonald Hasting’s subtitled it “A Lifetime of Shooting and Murder” that alludes to both Churchill’s forensic firearms work and his enjoyment of shooting. In turn-of-the-century Victorian Britain, the facts were that formal forensic work by the police was in its bare infancy. It wasn’t until 1901 when Scotland Yard established a fingerprint department, and it was 1912 before an official police photographer was named. Many such as pathologists and toxicologists remained outside of the official police department and as such, Robert Churchill was their gun expert. In this guise he developed the comparator microscope that allowed two bullets to be examined side by side leading to the matching of bullets recovered at crime scenes with those fired from firearms taken from those crime scenes or the person suspected of the crime. At his “premises” on Orange Street at the corner of St. Martin’s in London, Churchill had a test range in the cellar where shots were but a dull thump to any passersby above. There he checked whether the slugs dug out of a corpse could have been fired from the exhibit gun. His findings led many a miscreant to a “long drop and a short rope,” as was the frequent punishment handed out by Victorian England courts.

Churchill’s daybook contained a variety of notes such as, “Re: The above named who is in custody in this city on a charge of attempted murder, I enclose for your examination…” or, “Lord R. wants to know how soon his guns can be stripped and regulated. S.P. invites you to shoot Saturday. H.R.H. requires 500 cartridges loaded No. 6 1/2 shot. Trigger pulls on J’s gun are 3 1/2 pounds….”

Churchill XXV Hercules grade 20 bore boxlock ejector single trigger game shotgun. Photo Courtesy Morphy Auctions.

Like many gun shops in England, there were multiple floors and, when entering the Orange Street premises, one was greeted by a Dickensonian character named Jim who separated those who were merely curious from those ready to spend pounds sterling on a bespoke shotgun, who were then ushered into a tiny “lift” to the second floor. While E. J. Churchill did not use a proprietary action, he turned out fine bespoke shotguns in great numbers, including his pet XXV gun.

Churchill perhaps was the oldest of the original gunmakers when he died in 1958. He amassed a small fortune from his businesses of gunmaking and putting criminals on the gallows, all the while shooting pigeons, grouse, pheasant and all manner of game as guests at the very best shoots. Churchill made and sold guns to the crowned heads of Europe including the Duke of Windsor who was briefly King Edward VIII before he abdicated to marry “the woman I love,” American divorcee Wallis Simpson, and the likes of British film producer J. Arthur Rank—all part of the golden age of game shooting.

Robert Churchill was not only a gunmaker, but an excellent shot. He often competed at pigeons in Monte Carlo and at Spain’s exclusive clubs and was invited to many large driven-game shoots across Great Britain. Churchill, unlike many who shoot well but cannot translate their success to teaching others, did understand how to be a successful shot, and in 1925, published How To Shoot that was revised in 1927 and later became, in cooperation with author Macdonald Hastings, the more definitive Game Shooting. It is in these books Churchill spelled out proper footwork, gun mount and other aspects that provided an interested shotgunner the means to become a fine shot. Nearly a century later, Holland & Holland, Brian Bilinski’s Fieldsport and others still teach the “Churchill system” at their shooting grounds proving his validity as the basis for good shooting.

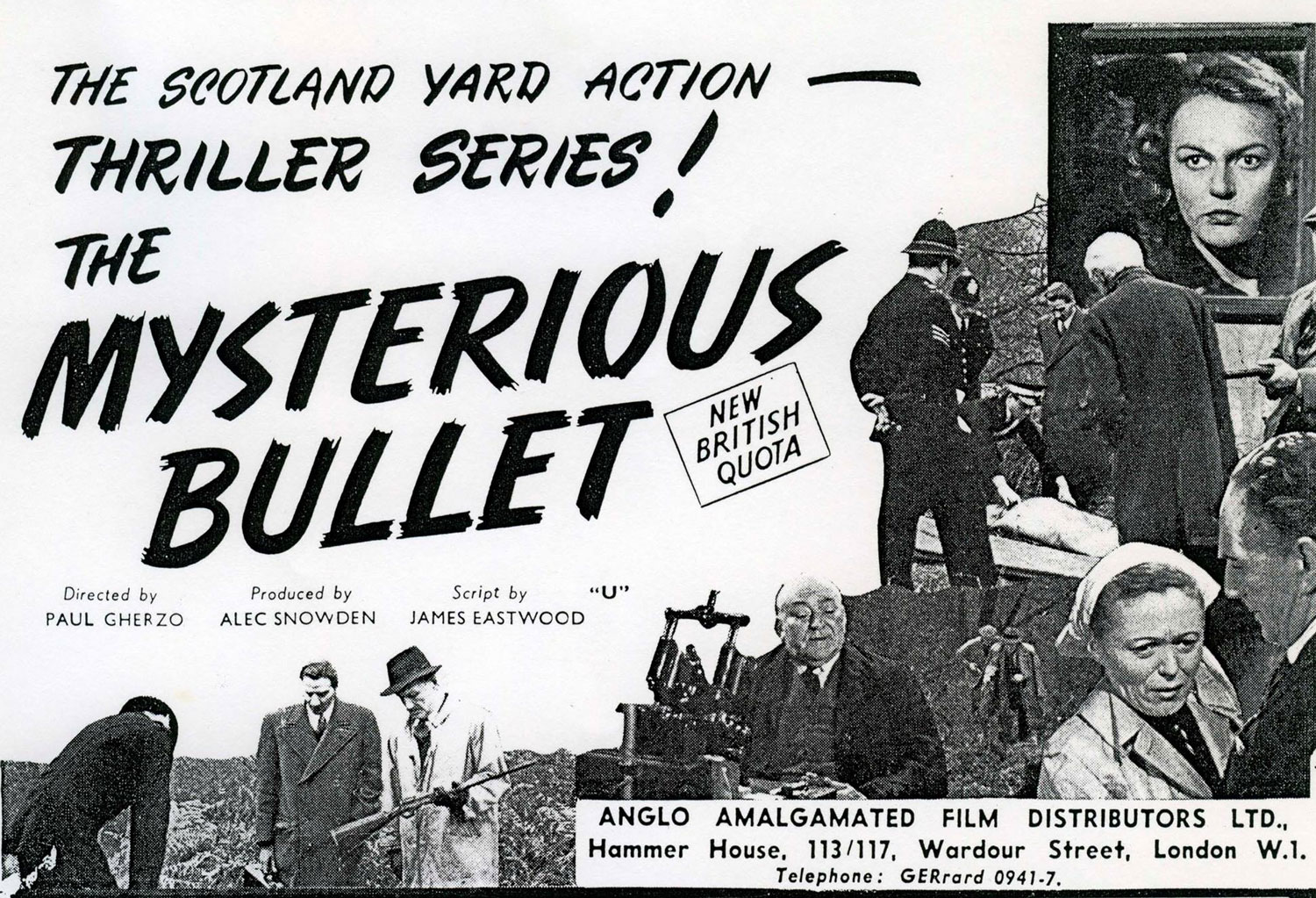

In 1955, Churchill became a film star of sorts, appearing as himself in a 31-minute crime short called “The Mysterious Bullet.”

While Americans feel shooting is an imbedded gene, the British take the attitude that shooting instruction is important and an even more important yearly refresher before the shooting season is a given. Hence, all of the gunmakers had their shooting grounds where you would go for a fitting if you ordered a bespoke shotgun or for your pre-season brushing up. It should be emphasized that if you were invited to a day’s driven shooting, you were expected to be able to hit your share of birds or most likely not be invited back. Churchill made this point by calling it “blotting your copybook,” which compares poor grades in school to equally poor shooting.

Churchill’s teaching elaborated in his books is based on moving the gun from the feet up. For a bird coming to your left, you pivoted on the left foot and pushed around with the toe of a raised right foot and vice-versa for a bird on the right. The gun mount is practiced so that your fitted shotgun, which all-importantly shoots where you look, comes to your face at the instant the lead is achieved and simultaneously the shot is fired. Perhaps the secret of Churchill’s shooting style is his belief that the correct way to shoot any moving target was to engage it at the rear then accelerate through the bird firing the instant the gun passed the beak. His reasoning was that the over-travel of the gun through the momentum of the swing would move it sufficiently in front of the bird to provide the correct lead. Churchill’s style of shooting requires practiced timing, and if that is applied, it works every time.

Perhaps the importance of the Churchill system was emphasized by Holland & Holland’s then-Chief Instructor, now retired Vice President, Ken Davies who repeatedly emphasized “being on the line of the bird,” by engaging at the rear and continuing through to the beak. In so doing, your pattern is centered on the bird and all that’s necessary is to get far enough in front to connect. Several instructors use the same philosophy such as “butt-bird-beak” or other such saying. Davies stated often that as many shots are missed either over or under the bird than can be attributed to faulty lead.

In step with his shooting system of swing velocity equals lead, Robert Churchill introduced his controversial XXV shotgun that was then refined between 1913 and 1915. The XXV had short 25-inch barrels and a unique V-shaped raised rib. Arguments for and against the rib have been carried on among sportsmen since the rib’s introduction in 1913. In Game Shooting, Churchill explained the somewhat controversial inverted-V-shaped rib as, “the rib taper is specially designed to harmonize with the perspective effect of the barrels. When the gun is mounted to the shoulder the result is astonishingly effective, for a twenty-five-inch barreled gun is thus made to convey to the eye the effect of a full thirty inches…. The optical illusion is so complete that he will find it impossible to measure the barrel length with his eye.”

Hastings said of the XXV, “while they don’t suit everybody, they are a boon to many, especially to middle-aged men and those with physical disabilities who think their day is done. I can’t honestly recommend them to a big-boned tall man.”

Robert Churchill was a trailblazer in forensic exploration of firearms as they related to the commission of crimes. He too set the stage for an ongoing style of shooting and shooting instruction that endures to this day. His controversial XXV shotguns also live in gunrooms as used shotguns of great quality. The fact that they were copied by the great Spanish gunmakers such as AyA show that while controversial and not everyone’s cup of tea, the XXV endures. So perhaps not quite as eloquent as Winston, Bob’s writings and fine shotguns live on today if merely hidden from many by the pages of time.

This article originally appeared in the 2021 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.