If there is a moral to being a sporting artist, it is the necessary presence of a practical interaction between the artist and nature.

There is no substitute for being there and getting some scratches on your pants, so to speak; soaking up the feel of the place and the action, wherever the picture is happening. This outdoor connection must be maintained and nurtured, whether we like it or not (Have you ever heard of a better excuse for going hunting? Sorry, Dear, I want to get to the storm windows, but today I’m morally obligated to chase grouse). Despite my levity, this is an absolute truth.

Training the Pup

Early in my life I didn’t think of myself as an outdoorsy person, though in retrospect it is obvious I was attracted to nature more than I realized. I was raised in Hammond, Indiana, a cinder-strewn city in the middle of the steel district, locally known as “duh region” and not exactly a jewel-like setting, from which I probably became an artist in self-defense. As kids many of us “hunted” with our BB gun s and slingshots; sparrows and garter snakes being our elusive quarry — a rabbit was big game Later my dad taught me something about shot-gunning on the then deserted strands west of Gary, where we’ d bounce tin cans along Lake Michigan with his old Ithaca double. On summer vacations I learned to use his flyrod back in the days when you pretended to hold a tobacco can under your casting arm.

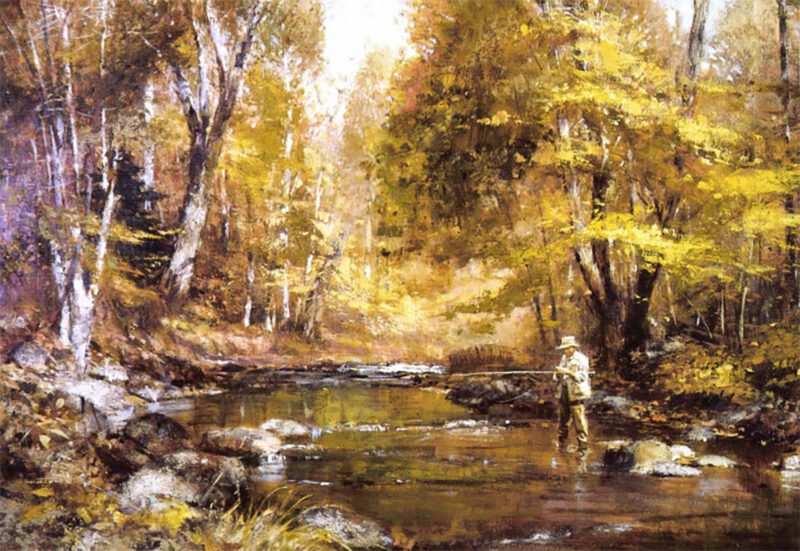

Autumn Pools depicts a small trout stream near the artist’s home in Connecticut. “There’s no denying that painting water is a stumbling block to many artists,” says Abbett. “It certainly has given me some rough times. My aim here was to show the right color — not always blue — and describe the surface of each stretch in the river.”

The first half of my art career was spent as an illustrator in Chicago and then in New York, during which I did a number of outdoor and adventure subjects, hunting and fishing scenes included. Most important, I learned that a special mood or storyline was necessary to bring the viewer into a picture, whatever its subject. When I moved into gallery painting and sporting art, this philosophy proved even more vital along with the caveat that paintings must smack strongly of personal outdoor experience.

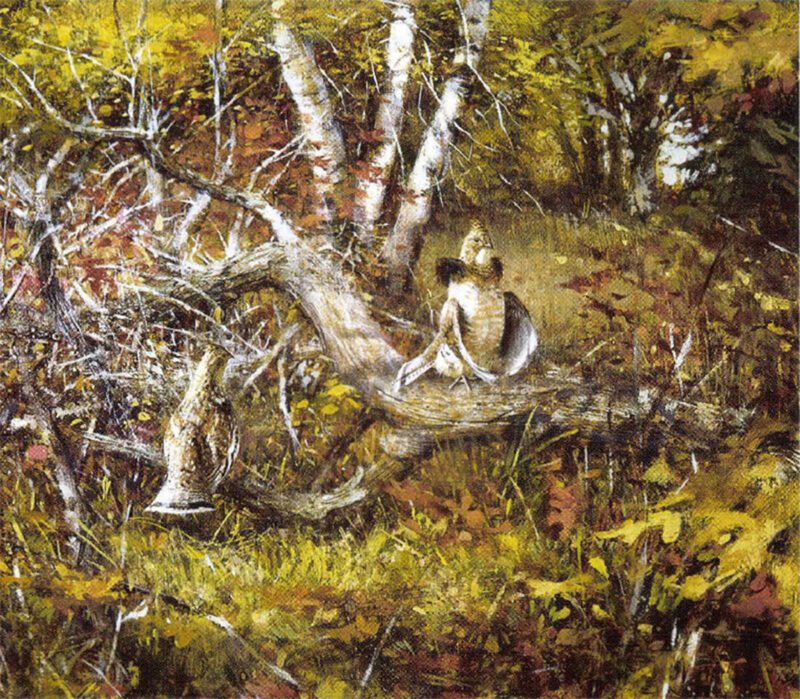

Training the Pup is a fair case in point — its storyline is simple the relationship between hunter and a young dog in that small slice of time when they develop a lifelong bond. Is there really a bird there? Will your dog be steady to wing and shot? It is not unlike the feeling you had when you let go of your kid’s bike for the first time. How many of us have lived that same moment?

In Happy Dog – Golden Retriever, Abbett set out to show that some breeds of sporting dogs actually look good with their tongues out. Says the artist, “Sportsmen can recognize the various expressions of their own dogs. To me, the smile on this golden retriever tells us that all’s right in his world.”

In 1985, I wrote an article for the November/December issue of this magazine describing some of my adventures in sporting art, and in it, I mentioned being on a commission trip to the piney woods of South Carolina to paint a portrait of an English setter. It was there, on a tranquil November morning, that I noticed all the people involved in the operation stretched out behind me — the plantation owners, one or two trainers, a mule driver, a visiting knighted gent leman from Scotland, somebody’s girlfriend, etc., — and said to myself, “Abbett, you sure better know what the hell you’re doing!”

Well, I’ve spent much of the last twenty-odd years trying to make sure I “know what the hell I’m doing.” The painting of the setter did turn out all right; I did visit Sir William Gordon-Cumming at his estate, Altaire, and I did paint his dogs. I also completed several paintings for the owners of the setter. Seeing how one painting often spawns several others is reason enough not to spend all my days in the comfort of the studio. But the most important reason for being out in the field is that it is the only way good sporting art can be accomplished – for the artist to know what the hell he’s doing. We have to see firsthand where the birds flush and work with some well-notched gundogs, to leg it through the covers and along the trout streams enjoyed by so many outdoor-minded people.

The response to my early paintings revealed the hunger for sporting scenes and dog art that existed in the 1970s. When I concentrated on these subjects, a career began to take shape Having paid my dues with that flyrod and shotgun, not to mention chasing ruffed grouse halfway across New England, I found I could begin to do such pictures with some conviction and authenticity.

Few people have ever seen grouse drumming in the wild. It is generally believed the bird’s cupped wings move with enough force to pneumatically generate this rhythmic sound. This is River Quail, 1979

Hunting the Edges is typical of the grouse cover around our Connecticut place, where to me, bringing home an idea fora painting was more important than limiting out. And most important has always been to capture “the feel” of being there at that moment. I have to agree with the late Ogden Pleissner, who in his one and only book (1984), mentioned that he would never have found the scenes he painted if it weren’t for his hunting and fishing.

My art led me to meet people and visit shooting estates and countless covers and streams that would make a sporting writer weep. While building up a credible storehouse of outdoor experiences, I also found that the people involved are usually strong conservationists. They’re more interested in watching a good dog than filling a bag limit and often work hard to insure the next season’s game crop.

“After years of chasing grouse,” says Abbett, “I’ve learned that they can often be found along forest edges. The birds feed on berries, clover and other foods in the open, sun-washed areas, but if danger threatens, they’re only a few wingbeats away from thick cover. I guess you could say that Hunting the Edges is my tribute to this well-known tendency in grouse behavior.”

I’ve been privileged to shoot at several well-known southern plantations and shooting clubs such as Clarendon, Wild Fair, Riverview and Borderline, to name but a few. To a relatively untraveled northerner, doing the southern quail shooting routine complete with a mule-pulled Thomasville wagon and a lunch served on red checkered tablecloths, was one of life’s finer treats. I found the gently slower pace of the South something I could comfortably grow into. It was at one of these southern locations where, while working a dog for the camera, one lad sang out, “Hey, give the Yankee a gun and let’s see if he can shoot.” This was during my more competitive days, so I accepted the challenge and dropped the next bird a bit closer than the cook might have suggested.

C. B. Cox commissioned me to paint a typical bird-hunting scene at his Riverview Plantation in Camilla, Georgia, and my painting, Riverview Quail, was later published in a limited edition. I remember Mr. Cox was as proud of his customized hunting Jeep as he was of his sprawling shooting facility! Again, being there enabled me to paint the picture with conviction and accuracy.

Two pointers watch a gaudy ringneck clatter skyward in At the Edge of the Cornfield. “The trick was to show just enough to say ‘corn’ without painting every stalk and kernel.”

Quite a way northwest of Georgia, near Minneapolis to be exact. I found myself on the back-water lease of Dan Luther, where we worked his dog “Rocky” in preparation for his portrait. Having all the appropriate gear assembled in one place, at the proper location in the right season, made this painting a pleasure to do, and of course made the portrait extremely personal to Dan. The remaining prerequisite was to (try to) portray the intensity and excitement of the dog.

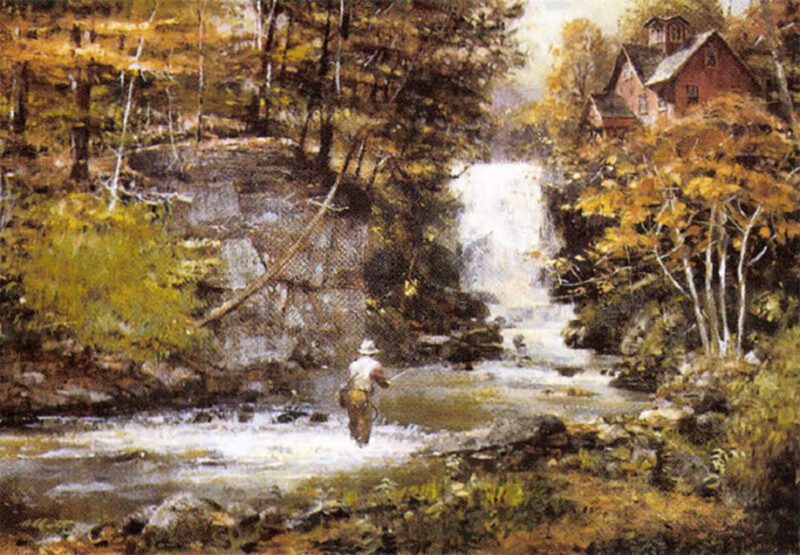

Sometimes, though, the home scenes are right there waiting to be done. I found the setting for Ruffed Grouse less than a half-mile from my studio, and Autumn Pools was painted from a delightful stretch of Pond Brook near Newtown, Connecticut. no more than ten miles from our home. Pond Brook has awarded me with many more paintings than fish, for that matter. I know that when I see a fisherman standing in a good-looking stream and tying on a fly or checking the current. it gets my juices going and there’s no rest till that painting is underway!

Preston Falls, a 24 x 30 oil completed in 1995

During these past years of my involvement with outdoor paintings, I’ve been conscious of a marked erosion in the public acceptance of (other people’s) shooting and hunting sports. This troublesome attitude, I would guess, is but one symptom of a wider agenda which is constantly being pushed at us. I hope my art, in its own way, can remind folks of the traditions we should actively strive to retain. Fortunately, I do see a consistent vein of outdoor-minded people who quietly and firmly continue to pursue and enjoy hunting, fishing and shooting They may not make as much noise as their antagonist s, but they’ll not give up these activities easily. Just as one painting may spin off several more, hopefully these traditions can and will be passed along to many others after us.

Brittany Head Study III, a 16 x 20 oil which appeared on a sold out print by Wild Wings.

Sporting art, like wildlife art, got a considerable leg-up from the almost manic popularity of environmentalism since 1970. Back then, there were half-a-dozen artists known for this subject matter as compared to hundreds today I’m always leery of manias and fads, and though western art proved to be robust and lasting, I believe wildlife art has settled into a more realistic level. Now I can only hope that environmentalism itself can find a more cautious and mature level from where it can continue the truly meaningful services it was meant to attain in the first place.

Where sporting art will go from here is difficult to say. It certainly depends upon the artists who take it up; if their personal goals and experiences coincide with their talent and love of nature, the genre will be with us for a long time. I recently wrote an article for Wildlife Art magazine in which I time-lined the lives and careers of sixteen deceased wildlife and sporting artists. The results were inspiring — nearly all were outdoor people from the get-go; many were drawing animals and birds in early childhood, and almost all grew up to be hunters and fishermen. These guys were real brush-busters— they had a paintbrush in one hand and either a flyrod or a shotgun in the other — or both.

“After years of chasing grouse,” says Abbett, ” I’ve learned that they can often be found along forest edges. The birds feed on berries, clover and other foods in the open, sun-washed areas, but if danger threatens, they’re only a few wingbeats away from thick cover. I guess you could say that Hunting the Edges is my tribute to this well-known tendency in grouse behavior.”

It is my hope there are more talented, individualistic outdoor men coming along who, if they can tear themselves from their VCRs and get out into the bush, will continue to make the sporting art we’ve known and enjoyed for so long.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now