Instead of just two bulls, Theodore Roosevelt and his party were suddenly confronted by a huge herd of angry Cape buffalo.

The buffalo rose like massive black warriors from the papyrus swamp. Theodore Roosevelt and his party had just come face-to-face with one of Africa’s most dangerous animals.

It was 1909 and TR’s safari had arrived at Hugh Heatley’s 20,000 acres located between the Kamiti and Rewero Rivers in British East Africa (now Kenya).

Heatley was helping to guide TR, his son Kermit, and safari leader R. J. Cunninghame through the tall grass and clumps of papyrus. They were searching for the “black ghosts of the papyrus,” the Cape buffalo TR needed for his museum collection.

Earlier, Heatley had suggested they dismount, leave the horses with the syces (groomsmen), and walk to the distant swamp. The papyrus stood more than 20 feet high in some places, and the stems grew so close together that once inside the stand, the hunters couldn’t see more than a few feet in any direction. There was also the problem of waist-deep mud and water. Escaping an emergency here seemed impossible.

They decided to take advantage of a half-dried riverbed that ran roughly parallel to the swamp. The watercourse twisted and turned through banks four and even five feet high, so it was difficult to see the buffalo herds.

Cunninghame, an experienced white hunter, knew full well the dangers of hunting buffalo, especially when at a disadvantage. While Heatley went on ahead to scout for buffalo farther down the trail, Cunninghame took control and told the hunters to creep up the watercourse, keeping their heads down while crawling on all fours.

Before long the hunters spotted what they thought was a small herd of buffalo about 200 yards away. As they slipped toward the herd, two bulls caught sight of the men and rose from the grass adjacent to the swamp. Shots immediately rang out from the hunters’ double rifles and both bulls went down while the rest of the buffalo scrambled to their feet. But instead of a dozen or so as they had originally thought, the herd numbered more than 75 buffalo.

TR, who had also wanted a cow for his collection, singled out a mature female and fired. Only injured, she turned and limped within the sanctuary of the herd, which had closed ranks and formed a semi-circle while advancing toward the men, their massive heads outstretched in a threatening manner. The hunters froze, not wanting to invite a full-scale charge, which would mean certain death for some of the men, if not the entire group.

“Stand Steady! Don’t run!” TR shouted, as Cunninghame, with his arm on Roosevelt’s back, called out, “And don’t shoot!”

A few tense seconds passed before the herd turned and pounded away. The hunters then concentrated on recovering the downed buffalo.

Edmund Heller and J. Alden Loring, both renowned zoologists and naturalists, supervised the skinning process right at the site. A native team of skinners worked carefully and dutifully under Heller’s watchful eye. Sometimes the cleaning process would take days and separate camps had to be set up, complete with askaris (native soldiers) to protect the men and trophies from marauding hyenas or lions.

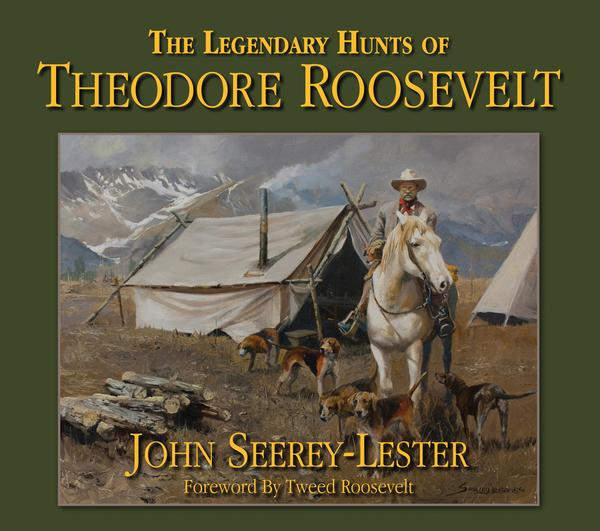

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now