When I fired my first shot with a centerfire rifle, only about half of all hunters used scopes. Offhand, squinting down the Krag’s long barrel and struggling to hold it up, I tugged the trigger. The report savaged my ears, the steel butt my clavicle. The oil can on the furrow escaped injury.

Thirty years earlier, before a Zeiss engineer trimmed light loss on lenses with coatings of magnesium fluoride, 24-year-old Bill Weaver designed a riflescope and built it by hand. His slim 3x prompted many hunters to consider an optical sight. Priced at $19 with a “grasshopper” mount that resembled a giant paper clip, the 330 was much less costly than Zeiss scopes (the 4x Zeilvier listed for $45 in 1926!). Weaver fitted the 3/4-inch tube with internal windage and elevation adjustments: 1-inch graduations for windage, 2-inch for elevation. A flat-top post was the standard reticle; a crosswire added $1.50 to the tab. Many hunters who bought a 330 would later upgrade to Weaver’s K2.5 or K3, Lyman’s Alaskan or the Redfield Bear Cub first manufactured by Kollmorgen.

By the 1950s Leupold & Stevens had shifted its manufacturing emphasis from surveying and hydrologic devices to riflescopes. The industry quickly adopted Leupold’s clever practice of replacing air in scope tubes with nitrogen to prevent fogging.

For effect, few riflescope developments since can match those pioneering strides!

Reticles, though, have changed a great deal. No one mourns the heavy horsehair reticles whose weight became inertia under sharp recoil. Many broke. Rough-edged by dust and routinely off-center in scope fields, they gave way to fine wire, then etched reticles. Engineers learned how to keep reticles in the middle of the field through windage and elevation adjustment.

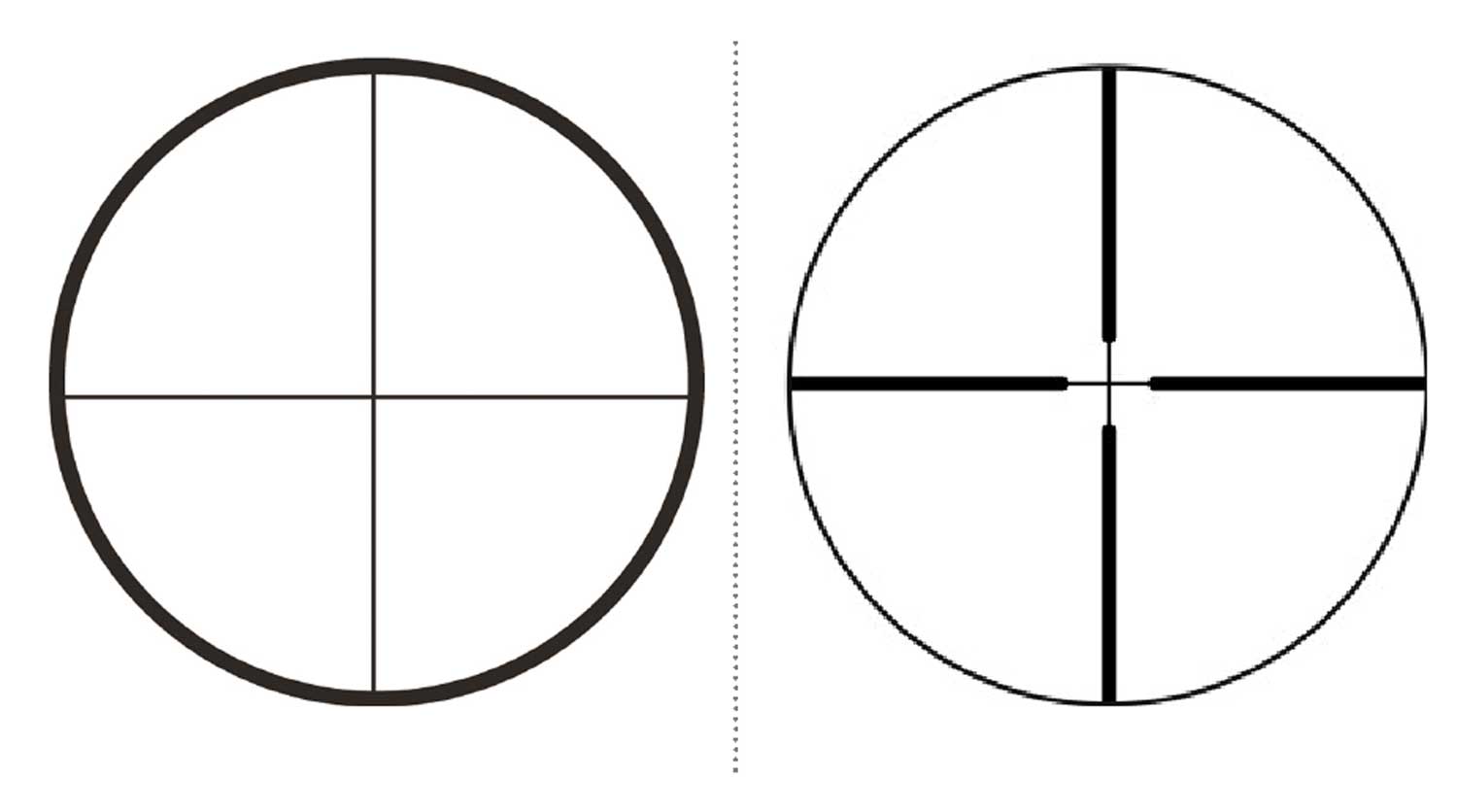

The hair comprising early reticles (left) caught dust; its inertia broke it in recoil; adjustment dials moved it off-center. Now etched, this simple reticle is still useful for hunting or competition. Leupold announced its brilliant Duplex reticle (right) in 1962. Now most scope-makers offer a “plex.”

Post and post-and-crosshair reticles were popular early on because most hunters grew up with iron sights. In military service they aimed with the blade front sight of the ’03 Springfield or, later, the Garand. A post came quick to eye in cover, and sight pictures looked much like those of a blade sight in an aperture. Most game was shot at woods ranges with cartridges of limited reach, and the small fields of view imposed by high magnification slowed aim. So hunting scopes of that era were overwhelmingly 2 1/2x to 4x.

Not that there weren’t reticle options. As early as 1926 Zeiss cataloged a #1 range-finding “graticle”: a post and bars, the gap between bars subtending 25.2 inches at 100 yards. Still, into mid-century, few hunters saw a need to fire much beyond the point-blank range of the 30-30, let alone the 30-06. For fast aim, they found the simplicity of the post and the crosswire endearing.

As a youth, I marveled at T.K. Lee’s .008-inch dot on spider web. That reticle was late to scopes, because making a dot “float” in the field of view and respond to adjustment dials was difficult. Reportedly, an enterprising hunter in the Northwoods tied fine lynx hair in a knot to fashion a dot. Other efforts followed, but commercial success was elusive until Lee, of Birmingham, Alabama, offered a dot that 1) appeared clean-edged and round, 2) could be sized to order and 3) withstood violent recoil. It was suspended by strands of black widow spider web. Oddly enough, he refused to patent this reticle. So instead of becoming public knowledge at a patent’s expiration, the magic behind the Lee Dot passed to Dan Glenn, his assistant.

Later, optics firms probed ways to replicate, then perfect, what T.K. had pioneered. I’ve watched dots installed on spider web. These all-but-invisible filaments are manipulated by keen-eyed, short-tempered people in dark, dust-proof and breeze-proof booths. Enduring my brief visit, one snarled, “Don’t breathe.” Her hands were mannequin-still.

Still sold in a few target scopes, dots have left the reticle rosters of most hunting scopes. A pity. I like the dot. No thinking required. Just put it where you want the bullet to land and fire. The dot obscures almost nothing. There are no wires, bars, tics, numbers or other dots to confuse you or pull your eye off-target—nothing to delay a shot or tempt you to over-think it.

The dot’s signal liability: It can vanish in dark places. Long ago I met an elk in evening’s shadows. Slowly my rifle came to cheek. But I couldn’t see the Lyman Alaskan’s dot against the animal’s dark shoulder or shaded timber behind. I tried looking off center, as if for a faint star. No luck. Desperate, I pointed the .300 at a patch of bleached grass. There! Moved to the elk, the dot winked out. In a last-chance effort, I went back to the grass, glued my eye to the reticle and jerked it up, firing as it disappeared in the elk.

Wayne finds a 2-7x Vortex with plex reticle a fine fit for his Boyd’s-stocked LAW rifle.

Dot size is expressed in minutes of angle, or inches subtended at 100 yards (a minute is really 1.047 inches at 100). For that evening elk, a 4-minute dot would have been a better choice than the 3-minute dot in my 2 1/2x scope. I think the 3-minute option ideal in 4x sights, 2-minute dots best in 6x. In variable scopes with rear- or second-plane reticles, dots appear the same size across the power range. A 3-minute dot at 4x becomes a 1 1/2-minute dot at 8x, as the target image grows. A smart choice is a dot just big enough to see easily against dark and cluttered background irrespective of the power.

Focus that reticle!

From the box, a scope probably won’t give you a sharp reticle image. Get it by rotating the eyepiece (after loosening its lock ring) or its rear extension. Point the scope at a blank northern sky, not at an object that will distract your eye. When the reticle appears sharp, rest your eye, then repeat. Use this setting until age changes your eyes.

Set in the first, or front, focal plane, a dot (verily, any reticle) stays the same size relative to the target as you change power. So a 3-minute dot at 4x is still a 3-minute dot at 10x, where it looks as big as a poker chip. At 2 1/2x that same dot, now very small to the eye, can be hard to find quickly in shadowed thickets. Because it effectively “grows” as you dial up power to smack small targets far away and “shrinks” when you power down for fast, close shots, a first-plane reticle of any kind seems to me ill-suited for variable scopes on most hunting rifles.

Dots as wee as 1/8 minute are fitted to powerful target scopes. The size of .22 bullet holes in X-rings at 100 yards, quarter-minute dots appeal to me in bullseye competition.

Reticle illumination makes dots of modest size easier to see in scopes for hunting rifles.

In 1962, Leupold flattened a section of .0012-inch platinum wire to .0004-inch to fashion its Duplex reticle, an alternative to the traditional crosswire. Posts intruding from the field’s rim direct the eye in poor light; fine wires in the middle afford precise aim. The “plex” form is widely copied now, and the top-selling reticle in hunting scopes. (“Duplex” is still specific to Leupold’s reticle.) Premier Reticle Ltd. has supplied scope-makers with wire ribbon plex reticles. They’re now also photo-etched, with .0007-inch metal foil. Chemicals strip away all but the final form.

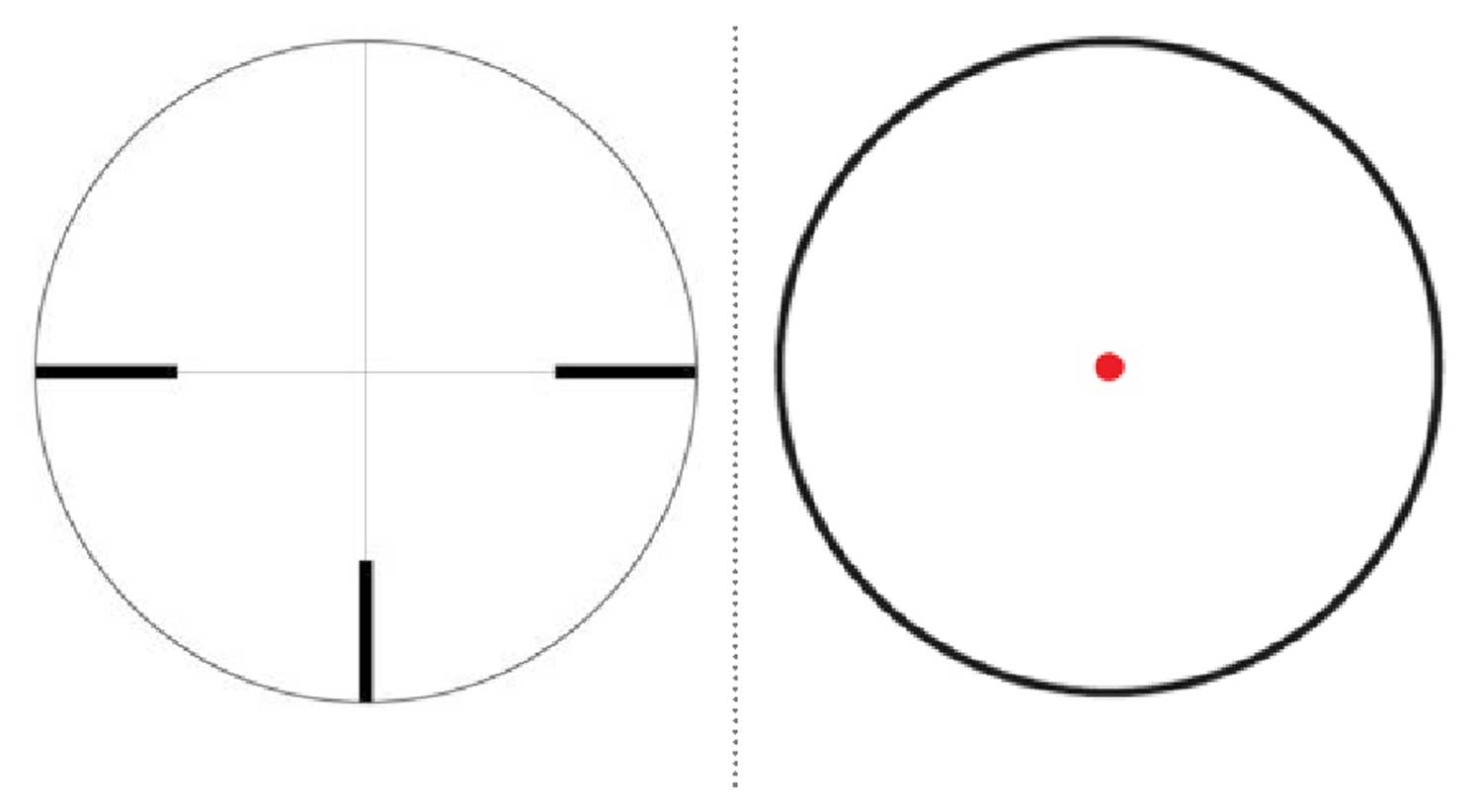

Like the Duplex, the German #4 (left) has “posts” for fast aim, slim center wires for more precision. It has no top posts—“no need to clutter the field or hide details with a post up there.” In good light, a simple dot, illuminated or not, (right) is delightfully simple and can be used to find range.

Even better, in my view: The similar German #4, with no post at 12 o’clock to cleave the field’s upper half. As a range-finding device, the #4 trumps the plex. Its three posts are square-ended, not tapered, so you get a quicker, more accurate read of reticle subtention.

Scopes that bring hits well beyond zero distance have a long history. Courting U.S. Army contracts in the early 1960s, Leatherwood Industries fitted a 3-9x Redfield with a cam calibrated for bullet drop. Rotating the cam moved the scope. This Auto-Ranging Telescopic Sight, or ART, followed a tortuous path into the 1980s.

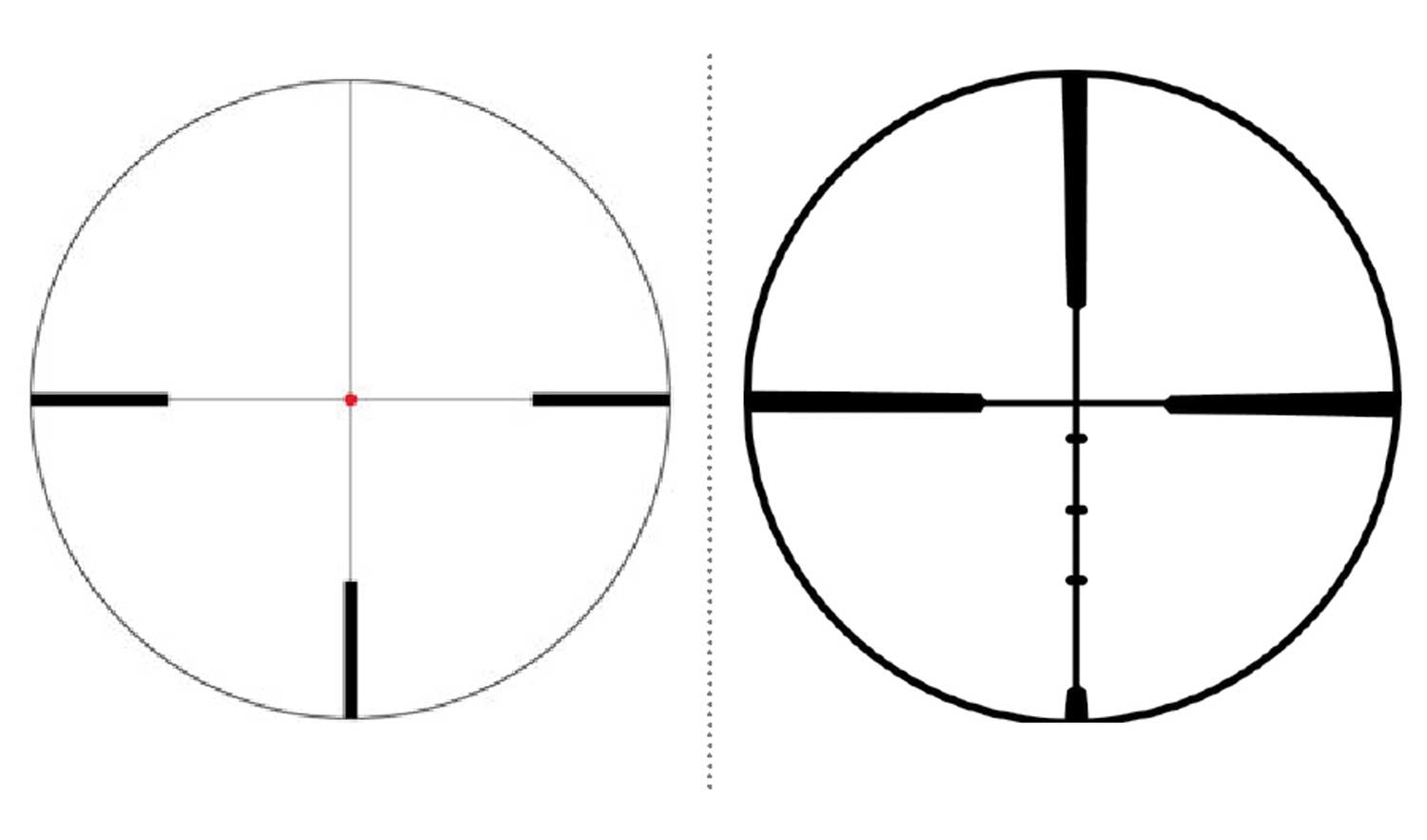

A lighted dot in a German #4 reticle (left) makes any short list for “best all-around hunting reticle.” With three tics for better aim at distance, the Burris Ballistic Plex (right) is still clean, quick on target.

In 1965 the U.S. Marine Corps adopted a 3-9×40 “sniper” scope with a reticle comprising two parallel horizontal bars at the top of the field, a separate first-plane ranging scale below. The shooter zoomed in on an 18-inch target or span until it fit between the top bars. The scale showed the range, from 200 to 600 yards. On a Remington 40x chambered in 308 Winchester, this scope became part of the USMC M40 rifle. Hi-Lux optics has reproduced it.

The Shepherd scope, a long-running optic designed for hunters, also employs second- and first-plane reticles to establish range. Circles of diminishing size “fit” targets at increasing range. They’re placed on the lower wire to provide correct aiming points.

Range-finding reticles with multiple tics, dots and wires proliferate. I’m impressed by the simplicity of the Burris Ballistic Plex. Three small tics are intelligently spaced on the bottom wire to help with holdover at long range. These once helped me take a beautiful pronghorn buck, when another group of alerted pronghorns blocked my approach. On paper I had confirmed bullet drop at each tic, so I knew where to hold for the 385-yard shot.

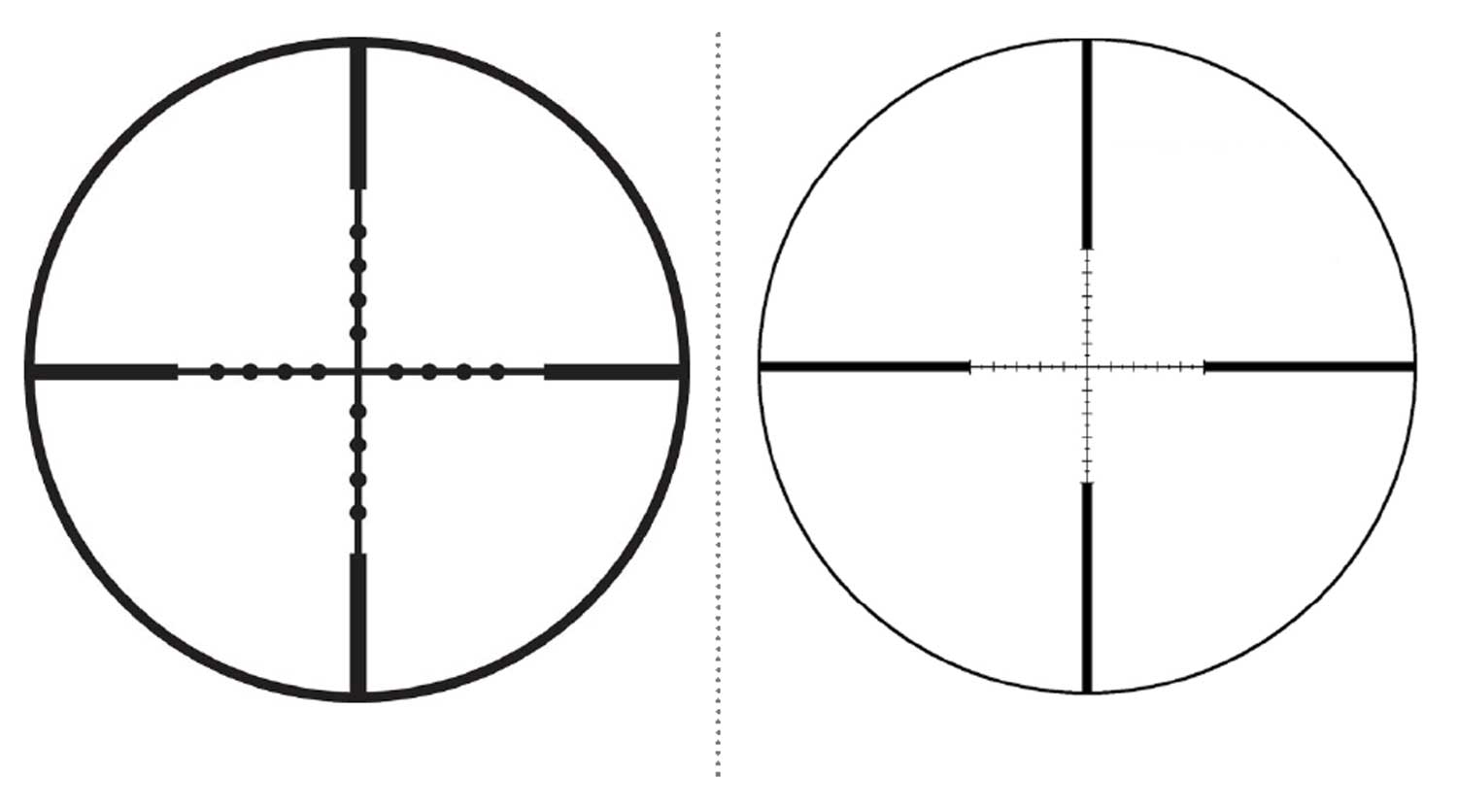

A Mil Dot reticle (left) helps you range targets and provides measured compensation for drop, drift. This reticle in a 5.5-22×50 Nightforce (right) has 1-minute tics, helps you hit small targets far away.

Most common in military circles but useful for hunters too, the Mil Dot reticle is based on the angular measure of a mil, shorthand for milliradian. A mil spans 3.6 inches at 100 yards, thus 3 feet at l,000. A mil dot reticle comprises a crosswire strung with dots a mil apart. Using mils to find range, divide target height in mils at 100 yards by the number of spaces subtending it. The result is range in hundreds of yards. If a buck 3 feet at the shoulder (10 mils at 100 yards) appears in your scope to stand two dots high, you divide 2 into 10 and get 5. The deer is 500 yards away. You can also divide target size in yards by the number of mils subtended, then multiply by 1,000 to get that answer. For the deer in our example: 1 divided by 2, multiplied by 1,000.

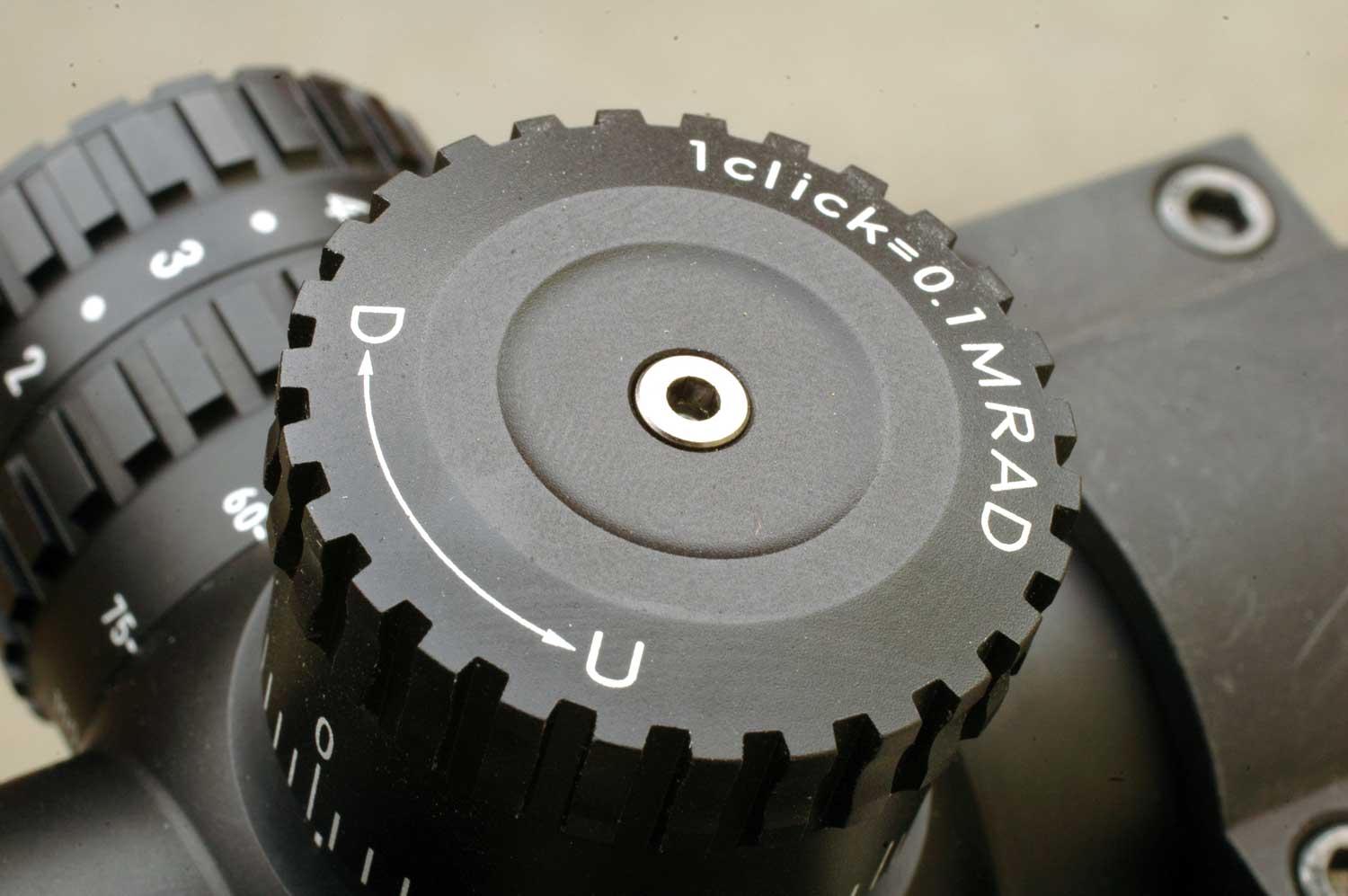

Minutes or mils? Your pick. It’s helpful to “think” in one or the other as you judge range, call shots, adjust dials. A turret with .1 mil graduations (here) pairs nicely with a Mil Dot reticle.

Variable scopes with second-plane Mil Dot reticles accurately range targets at only one power setting—usually the highest. First-plane Mil Dot reticles can be used at any magnification.

Laser ranging has upstaged “bracketing” reticles. While faster and more accurate, scopes incorporating lasers are heavy and bulky, and not everywhere legal for hunting.

In 2018, SIG added laser ranging to a new line of BDX (ballistic data exchange) scopes—without putting it inside. SIG’s BDX Kilo laser rangefinder stores data you enter for your rifle’s load. Bluetooth connection lets you “pair” that Kilo with your scope. Then, as you range a target, a red dot appears on the scope’s plex reticle. Put the dot where you want to hit. Fire.

More familiar with Depression-era Hensoldts than with Bluetooth voodoo, I was coached at BDX’s debut by product manager Joe Fruechtel. After checking 100-yard zero on a rifle in 6.5 Creedmoor, I picked a more distant target. A rangefinder paired with the 3.5-10×42 BDX scope pegged it at 430 yards. A red dot appeared on the reticle’s stem. Dot on the plate, I fired. Whock! Lit by two CR2032 batteries, the reticles have 10 brightness settings, “off” stops between, with auto shut-off.

“If you get a read on wind,” said Joe, “you can plug it into the Kilo’s data, picked up by the scope. A dot appears windward of the reticle.” There are 18 addressable wind hold indicators and 78 vertical hold points. Dots at the ends of the horizontal wire are Level Plex indicators to nix canting. You can switch those off or boost their sensitivity, from a 3-degree cant to 2-, 1-, even a half-degree for greater precision. The adjustment dials provide 50 to 60 minutes of adjustment. But after zeroing, they’re unemployed. The rangefinder does the work.

To focus any reticle for your eyes (not distance!), use the eyepiece or (here) its fast-focus ring.

Separating laser ranging from the aiming optic makes BDX scopes legal in some places that prohibit laser-ranging scopes. These scopes are also of ordinary weight and dimensions, and affordable. At their debut, SIG had four BDX models with three-times magnification ranges, SFP (second plane) reticles and 30mm tubes and: 3.5-10×42, 4.5-14×44, 4.5-14×50 and 6.5-20×52. A series of six-times BDX scopes has followed: 1-6×24, 2-12×40, 3-18×44 and (with 34mm tube) 5-30×56. All can be used without Kilo support. For quick off-the-shelf use, SIG includes eight data sets for popular loads, absolving you of logging bullet and range data.

Best reticle? Depends on the task. To shoot game at ordinary ranges, my usual mission, a 3x or 4x scope with a Duplex, German #4 or 3-minute dot makes sense. But not long ago, bellied on a rock ledge, eyeing a mark a mile off, even a 2.5-10x scope proved inadequate. A pal handed me his rifle, a 6.5 Creedmoor sporting a Nightforce NXS 5.5-22×50 with a 100-minute elevation range. “You’ll need ’em all,” he grinned.

We did. At 1,300, then 1,680 yards—just shy of a mile—the power and adjustment range of that scope and its 1-minute reticle tics were invaluable. Even a light breeze had us counting tics on the horizontal wire. But that’s another story.