Perhaps the greatest Nash Buckingham story of all was the one he lived for himself.

One of the all-time great sporting scribes, Theophilus Nash Buckingham, was born in Memphis, Tennessee. He grew up amidst the genteel society characteristic of late 19th and early 20th century, and his parents likely were fairly well off. In truth, Mr. Buck, as he came to be known to a wide range of friends and admirers, rambled around the rim of a gaping canyon of poverty most of his life. His early ventures as a businessman proved unproductive, whatever he inherited from his parents vanished like milkweed spores in a September storm, a modest fortune his wife brought to their marriage disappeared over time and his productivity as a writer never netted a great deal of income. In the latter stages of his life the wolf of poverty howled at his door, and a cherished friend and wonderful gentleman cut in the Buckingham mold, Dr. “Chub” Andrews, almost certainly helped him keep economic body and soul together.

Those economic considerations being duly recognized, what a life Buckingham lived! He knew the golden era of the bobwhite first hand, shot ducks with many of the nation’s great sportsmen, and knew the joys of the Mississippi Flyway during what he would later describe, somewhat shamefaced, as “The Prodigal Years.” A consultant for Western Cartridge Company and Winchester for many years, he had shotshells aplenty, places to hunt, and ample quantities of that most precious of commodities, time. To look back on the span of his career, which spanned 90-plus years, is to be filled with wonder and more than a small measure of envy.

An individual whose bonhomie was matched by a powerful intellect, he studied first at Harvard and then, homesick, completed undergraduate work at the University of Tennessee where he was a four-sport star. The same marvelous hand-eye coordination that served him so well in a duck blind or quail field came into play in athletics. He was a major figure in amateur boxing and a fine football player, but once college years were behind him Buckingham rather drifted for a time. He wrote for the Memphis Commercial Appeal, owned a sporting goods store, and for a time held an associate editor position with Field and Stream magazine.

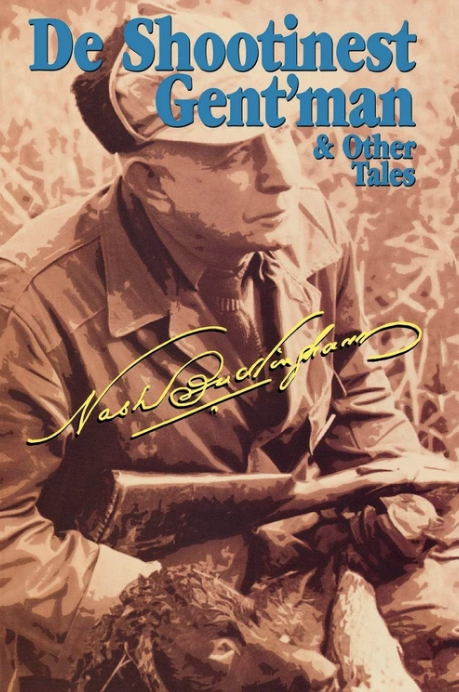

Nash Buckingham was without doubt the greatest outdoor writer of the twentieth century. His stories are told firsthand in the Ole Southern dialect. His vast experiences come from the heart of the Mississippi Flyway, the Gold Age of Wildfowling from the 1890s to 1940s.

Soon after his 1910 marriage to Irma Witt, he pretty much abandoned all pretense of pursuing other careers and gave himself fully to his first and consuming love — the sporting life. His prolific pen produced a steady stream of articles for leading outdoor publications, and many of those pieces formed the substance of his books — De Shootinest Gent’man, Mark Right!, Ole Miss’, Blood Lines, Tattered Coat, Game Bag, and Hallowed Years.

Those books, along with a work he co-authored with William F. Brown, National Field Champions, were spaced over a quarter of a century.

In addition to steady literary output, he was a respected, almost revered field trial judge, and having learned from his prodigality in shooting untold numbers of waterfowl in his younger years, he became a leading voice for conservation. He was a staunch and effective advocate of the federal Migratory Bird Treaty, a moving force in creation of the Federal Duck Stamp program, and tireless in his critiques of game hogs.

Over the course of his long and illustrious career (and beyond) Buckingham won a number of awards. Winchester recognized him as their Man of the Year; his speech connected with the acceptance of that award was a tour de force. Speaking without so much as a single note card to prompt him, he held his audience spellbound in a stirring and eloquent address.

In 1960 the Outdoor Writers Association of America (OWAA), of which he had been a moving force from its founding, recognized him with its top conservation award, the Jade of Chiefs. He is listed as one of the organization’s “Legends.”

Over the years I have written a great deal about Buckingham in various forms — introductions to reprints of several of his books, magazine pieces, newspaper articles, and on web sites. Perhaps sharing three distinctive and delightful experiences growing out of those efforts will provide some measure of the warm, winsome nature of the man and his exceptional knack for making friends.

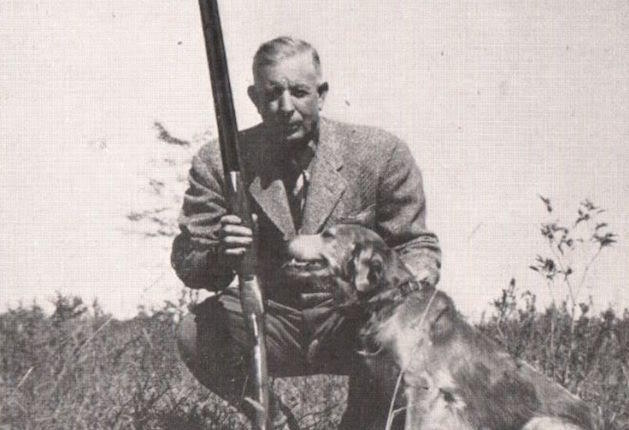

The first came when I was seeking a photograph of Mr. Buck and wrote a letter to that effect to the membership magazine of the OWAA. To my great delight, a few days after it arrived the mail brought a nice letter from a longtime friend of Buckingham’s who was a stellar writer in his own right, John Madson, enclosing a photo. Taken in Mr. Buck’s later years, it shows him holding a cock pheasant, killed at a hunt at Winchester’s famed Nilo Farms, aloft and admiring it.

That same appeal for material brought a response from Henry Reynolds, who was a successor of Buckingham’s at the Memphis Commercial Appeal as well as being his close friend. We subsequently got together when I was in that part of the country and Henry showed me a veritable treasure trove of carefully preserved correspondence from Mr. Buck. As I admired the lengthy letters, written with exquisite penmanship and invariably of considerable length, Reynolds made a wonderful gesture.

“Take one of the letters,” he said. “It will find a nice home with someone like you.”

Today it rests in a signed copy of one of the exquisite limited-edition Derrydale Press originals of De Shootinest Gent’man.

Several years later, in 1988, after exchanging some correspondence and phone calls, I had the opportunity to meet and chat with Chub Andrews, Buckingham’s closest friend late in life and his executor. Chub showed me all sorts of Buckingham memorabilia, from the Burt Becker magnum that replaced his fabled “Bo Whoop” shotgun to the medallion-bedecked hat Buckingham wore when judging field trials.

I left his Germantown home with not one or two but three treasures, and the letter on Chub’s personal stationery describes them perfectly: “This is to certify that the plastic greenhead decoy possessed by Dr. Jim Casada was one of the set of the last working decoys owned by Nash Buckingham. The railroad spike used as a weight came from the platform area of the now defunct railroad upon which the ‘limb dodger’ used to run. These are genuine mementoes of great moments that I shared with Mr. Buck at dear ole Beaver Dam.”

Glued to a platform holding the decoy is a Winchester shotshell from Buckingham’s final box.

Those are memories and tangible treasures to hold dear, just as legions of adoring readers cherish the writings of a man who was never surpassed in his handling of Negro dialect, in his ability to set a scene, or in the sparkling manner in which he told countless tales. He was a sporting scribe for the ages.