Joseph Hilberry Casada, known simply as Joe, was my paternal grandfather. Countless hours spent in his company during my halcyon days of youth served as foundational building stones for some key aspects of my life. In his inimitable fashion, Grandpa Joe introduced me to storytelling, provided hands-on exposure to the traditional mountain way of life, and was a walking encyclopedia of Smokies folkways. A man I idolized, he was most certainly a character—at times exasperating to his wife and children, more than a bit out of touch with the mainstream in about any area you could think of, and obstinate as only the most mule-headed of mountain folks can be. Yet with me, he was seldom judgmental, never really critical and seemingly always willing to listen to a pesky, eternally curious young boy.

Joe Cassada

Grandpa was unquestionably highly eccentric, but if anything, his idiosyncrasies only endeared him more to me. We were buddies in the special fashion only possible when a generation is skipped and those involved are, respectively, of appreciable age and quite young. In truth, Grandpa’s perspective and general approach to life closely resembled that of a youngster. He just had the misfortune of being imprisoned in an old man’s body. Offsetting physical constraints, however, was the decided advantage of being blessed with a lifetime of experience and his youthful zest for life.

Having now reached the approximate age Grandpa Joe was when my first recollections of him begin, I realize just how fortunate I was to have him as a mentor. He was a man of infinite patience with me although he had no tolerance whatsoever for a goodly portion of the adult world. He was distrustful of most of mankind, highly individualistic, perfectly comfortable in his own skin, religious after his own fashion, incredibly hardworking, self-sufficient and possessor of an endless array of tricks.

Thanks to his tutelage, I know how to make a slingshot and select the right type of wood for the task; have a solid understanding of down-to-earth subjects ranging from pulling weeds for pigs to dealing with free-range chickens; can find fishing worms; am able to store pumpkins, turnips, cabbage, apples and other foodstuffs so they will keep for months; hold an advanced education in the finer points of fishing for knottyheads; have solid grounding in many of the elements of storytelling; realize that formal education is by no means the only measure of a man’s intellect or his worth as a human being; am deeply permeated with traditional mountain culture; and most of all, have an abiding appreciation of the meaning of seeking oneness with the natural world. To my way of thinking, in leaving me those qualities as well as many more, Grandpa Joe provided me with a mighty fine legacy.

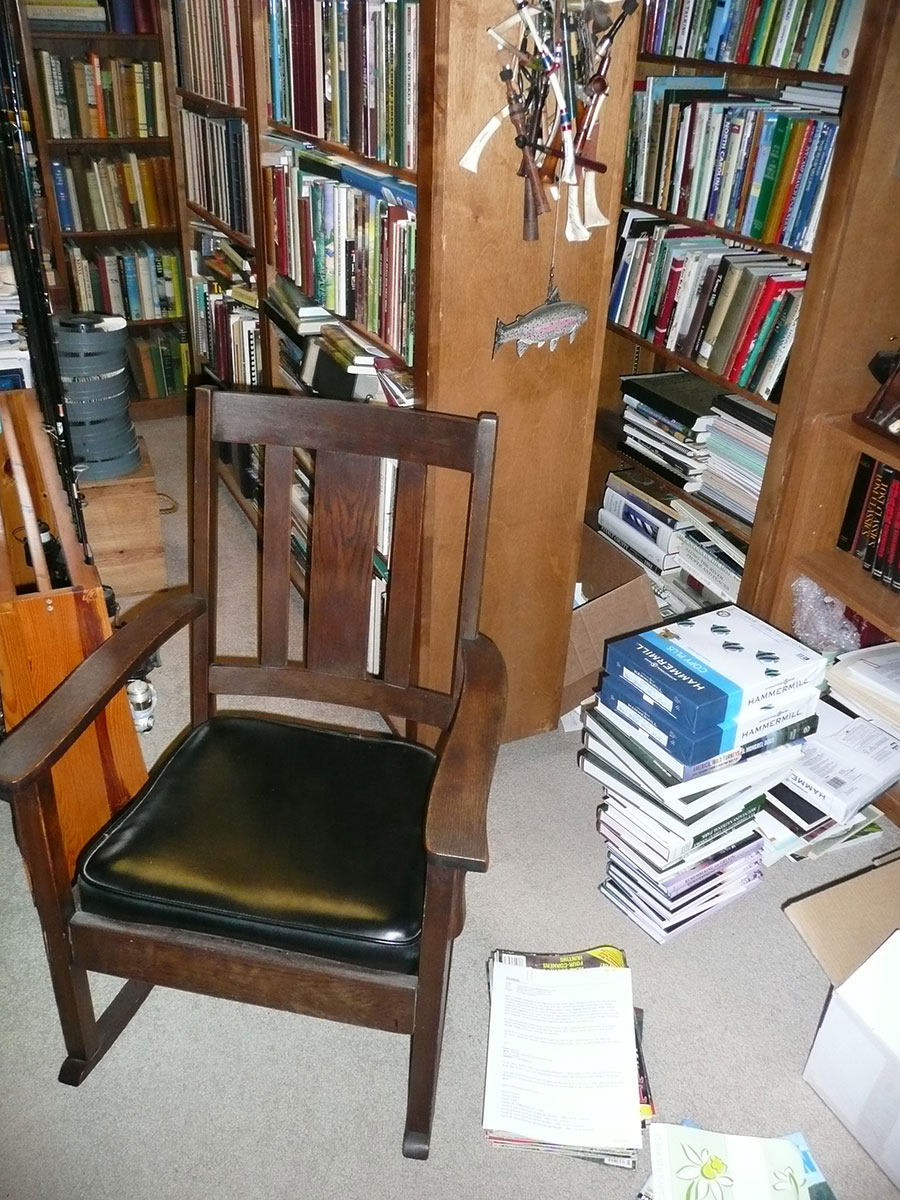

In terms of physical possessions, I have little to recall the man—the rocking chair where he held storytelling court now adorns my study, a single photograph of him by himself, a few family snapshots with him in the company of other family members and a push plow with which he worked his garden for decades. That’s it and it doesn’t matter. I have a storehouse of memories filled with riches miles beyond the measure of material things. As Robert Ruark said of “the Old Man,” all Grandpa Joe “left me was the world.”

Grandpa Joe (right) and Uncle Fred (left).

It was only with his death in 1967, when I was 25 years old, that realization of his legacy began to dawn on me. His death occurred in late February, which seemed to me somehow appropriate, because in our countless sessions of rocking chair relaxation in the heart of winter, as he eased close to the fire and muttered about what he simply styled “the miseries,” Grandpa often philosophized about the month.

“It’s fittin’ February is so short,” he would say, “because 28 days of it is about as much as a body can stand.” He would then opine that the best of winter’s hunting was over, “and besides, these gloomy days of rain and snow are a time for a spry young colt like you, not an old man like me, to be out and about.”

For all that he groused about weather, mistrusted mankind and clung to his independence with ferocious tenacity, it was never in Grandpa’s character to stay pessimistic for long. He had some pains associated with advancing age, but for the most part he ignored them while refusing to have anything to do with pain-relieving medications.

“I reckon an old man’s got a right to ache a bit,” he’d say, “but it don’t do to dwell on it.”

Never mind that he had known poverty all his years and had ample reason to be morose or feel downtrodden, Grandpa was a dreamer. In some senses he spent his whole life dreaming, although his visions and wanderings in the realm of wishful thinking lay outside normal approaches. If financial affairs meant much to him, I never saw any real indication of it, although whenever the subject came up, he always referred to “cash money.” He had so little of it that the redundancy was richly deserved.

Grandpa could outwork men half his age and never shied from doing so, although he was constitutionally incapable of following orders if they involved so much as a hint of supervision or oversight. You could tell him a field needed hoeing, a lawn required mowing or it was time for an orchard to be pruned. Just hire him to have at it and all would be fine. Look over his shoulder or make suggestions on how to perform the job, though, and it was time to seek someone else to handle the tasks. He was so completely his own man that no one, with the possible exception of Grandma Minnie on rare occasions, could tell him anything.

Grandpa’s rocking chair.

Grandpa’s dreams focused not on money but on matters such as the American chestnut’s return, the significance of planting black walnuts (he called them “grandchildren’s trees” because of their slow growth), olden times when he often heard the scream of a “painter” and even killed one, hunting pheasants (his word for grouse) when they existed in large numbers, and indeed sport of any kind. He lived a life partly cast in the past and for the rest looking to the future rather than being preoccupied with the present.

Hunting took primacy of place in his reminiscences, but he also ventured into romantic realms on the fishing side of the sporting equation. I loved to hear him talk about a time when speckled trout (brook trout) were so plentiful you could easily catch a hundred in an afternoon of fishing. Similarly, every time he recounted an epic battle with a giant jackfish (muskellunge), I listened in enchantment. Despite hearing that particular tale times without number, I felt that it never grew old. That’s a hallmark of a masterful weaver of words.

Sooner or later, and especially during the depths of winter when outside activities were limited, he would turn to a subject that brought me endless delight. Grandpa would abruptly switch from musing about matters dating back to the late nineteenth century and focus on the future.

“I’ve always liked figurin’,” he’d opine, “and it’s high time the two of us got busy doing some.” Or maybe he would suggest we needed to undertake a spell of “dreamin’ and schemin’.” Whatever his choice of words, the point of it all was quite clear. He had decided to quit reflecting on the past and start musing on the near future. He reckoned a good dose of planning about events to come offered an ideal antidote for anything from cabin fever to Grandma being vexed with the two of us.

Grandpa would then launch into a detailed plan of what we needed to do to get ready for spring fishing or maybe decide it wasn’t too late to make one more rabbit gum and set it in a likely spot. We might peruse that year’s Sears & Roebuck catalog to compare mail order prices of essential items such as snelled fishhooks or the new-fangled monofilament line with what they cost at the local hardware store. Or perhaps we would get several cane poles rigged and ready for our fishing forays come greening-up time. Year after wonderful year Grandpa showed me that dreaming is by no means the exclusive preserve of the young. You just had to be young at heart. That was one of his finest qualities.

Grandpa Joe never saw the ocean, but he fished pristine mountain streams and drank sweet spring water so icy it set your teeth on edge. He never drove a car, but he handled teams of horses and understood meaningful application of the words gee, haw, and whoa. I’m pretty sure he never left the state of North Carolina, but he lived a full life in the Smokies, mountains so lovely they make the soul soar. To my knowledge he never once ate in a restaurant, but he dined on sumptuous fare—pot likker, backbones and ribs, fried squirrel with sweet potatoes, country hams he cured from hogs he had raised and butchered, cathead biscuits with sausage gravy, cracklin’ cornbread, and other fixins the likes of which no high-profile chef ever prepared.

He never drank a soda pop, but he “sassered,” sipped, and savored pepper tea he prepared from parched red pepper pods like a connoisseur of the finest wines. He never tasted seafood, but he dined on speckled trout battered with stone-ground cornmeal and fried in lard rendered from hogs he had raised. He never ate papayas or pomegranates, but he grew cannonball watermelons so sweet they’d leave you sticky all over and raised muskmelons so juicy you drooled despite yourself when one was sliced. He never had crepes Suzette, but he enjoyed buckwheat pancakes made with flour milled from grain he had grown, adorned with butter his wife churned, and covered with molasses made from cane he raised. He never ate eggs Benedict, but he dined daily on eggs from free-range chickens with yolks yellow as the summer sun.

In short, Grandpa Joe was not, in the grander scheme of things, an individual who garnered fame, fortune, accolades or notable achievements. His life was one of limitations in many ways—geographically, technologically, economically, in breadth of vision and at least in the eyes of some, accomplishments. To my way of thinking, though, he epitomized love; the magic of mentoring; liberal dispensation of that most precious of gifts, time; and sharing of the sort of down-to-earth wisdom redolent in singer/songwriter John Prine’s suggestion that “it don’t make much sense that common sense don’t make no sense no more.”

Grandpa at home on the river.

I didn’t quite think, to echo a refrain from a poignant Randy Travis song about his grandfather, that Grandpa Joe walked on water. Yet seldom has there been a day since his death, now encompassing the passage of half a century, I haven’t thought about him. Invariably those thoughts bring a wry smile to my face even as they produce tightness in my throat. He blessed me with treasures beyond all measure, not the least of which was providing me an endless fund of anecdotes and tidbits of information to use in my writing. For that I owe him an enduring debt of gratitude. He was, in my small world, the most unforgettable character I’ve ever known or will likely ever know.

This piece from Sporting Classics’ Editor-at-Large and Book Columnist, Jim Casada, is a shortened version of a chapter in his forthcoming book, A Smokies Boyhood and Beyond: Mountain Memories, Musings, and More, which is to be published by the University of Tennessee Press later this year. To be notified when the book appears, or to sign up for a free subscription to Jim’s monthly e-newsletter, contact him at jimcasada@comporium.net or visit www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com.

Outdoor Chronicles is a collection of outdoor stories that will make you laugh out loud, and want to carry them wherever you go. They range from a fishing trip to Canada to a little stream that was better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek during a cold, dark, and dreary February, and many more. Buy Now

Outdoor Chronicles is a collection of outdoor stories that will make you laugh out loud, and want to carry them wherever you go. They range from a fishing trip to Canada to a little stream that was better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek during a cold, dark, and dreary February, and many more. Buy Now