For many years after Goodwin’s death, he was largely ignored in art circles.

His “real” specialty,” he told a friend, was painting “hunting scenes with action” for sporting goods calendars. Yet wildlife, hunting, fishing, and western paintings signed “Philip R. Goodwin” are in galleries, museums, and various public and private art collections throughout the United States and Canada.

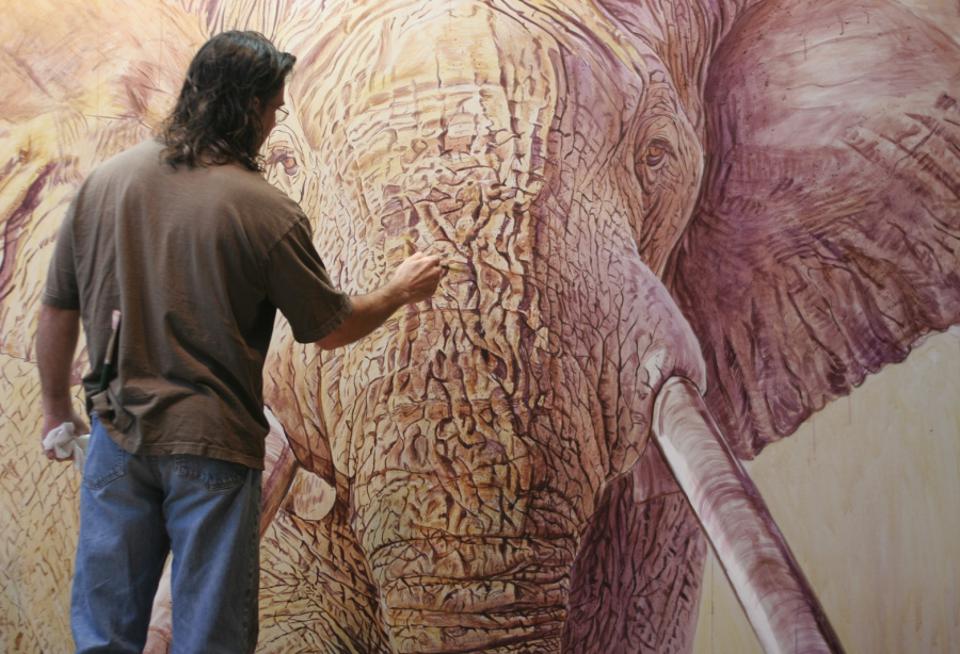

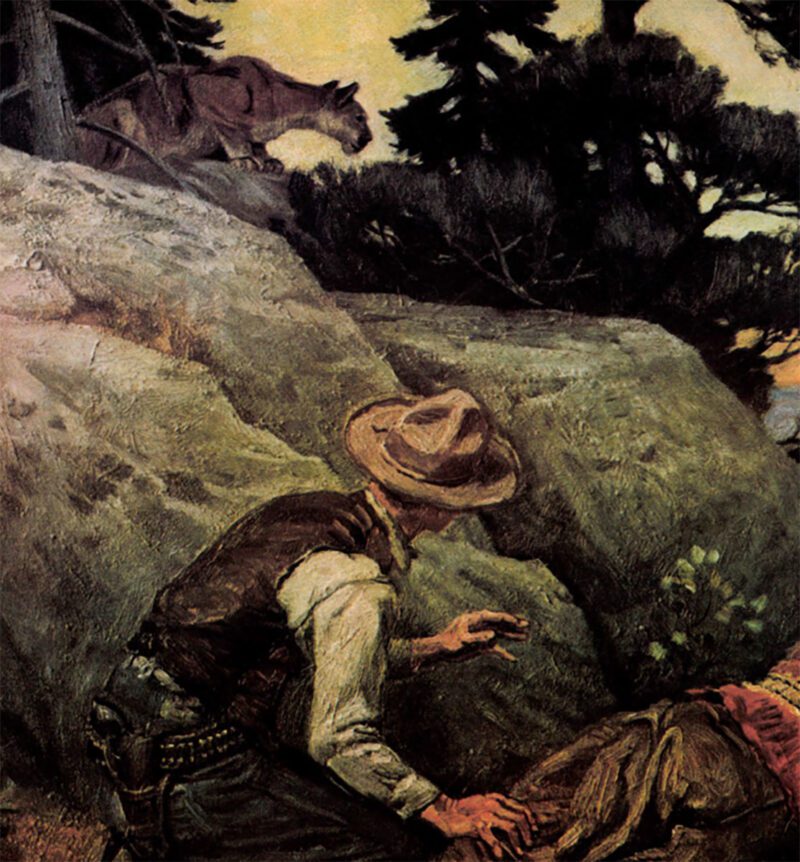

The Interrupted Shot (detail)

Considering the prominence of the artist’s work during his lifetime, and the great esteem in which his paintings, particularly those sporting scenes, are held today, surprisingly little is known about the man. himself. Even the American Museum of Natural History in New York, which for several years displayed a collection of Goodwin’s wildlife paintings, provided the public little information about the artist. Those paintings, originally commissioned by Theodore Roosevelt, were later moved from the museum to Sagamore Hill, Roosevelt’s home at Oyster Bay, Long Island, where they are housed today.

Philip Russell Goodwin was born in Norwich, Connecticut in 1881; he was the son of John B. and Ella Raymond Goodwin. He began sketching and painting as a child and at 11 made his first sale-an illustrated story to Collier’s. Four years later he was to receive first prize in a Harper’s Roundtable competition for his illustrated “A Story of Strife.” By this time, he was designing family Christmas cards and painting family portraits, including self-portraits.

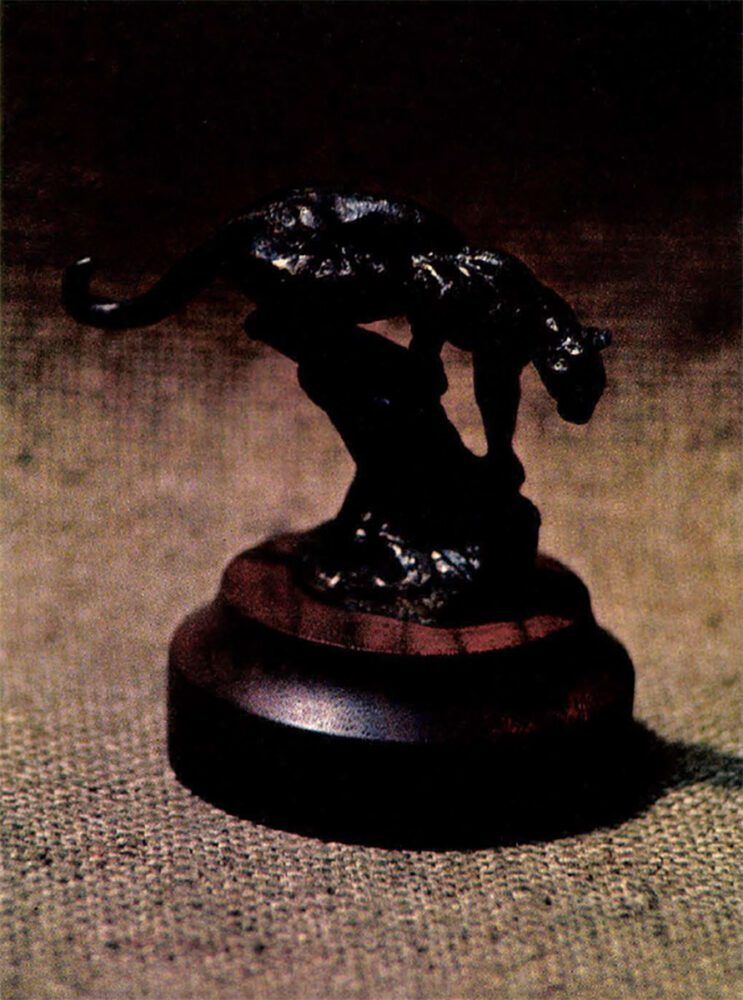

Mountain Lion 2 3/4″ high, bronze. Philip Goodwin tried his hand at modeling animals and casting them in bronze. Today his bronzes are prized art objects among collectors.

Philip Goodwin studied at both the Rhode Island School of Design and the Art Students League in New York City; but his greatest development as an artist seems to have been made during the time he studied under Howard Pyle, at Pyle’s Brandywine School at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Noted as an art school which accepted “only the cream of the art classes,” that “cream” included, in addition to the 17-year-old Goodwin, the great majority of the young men and women who were to become the leading illustrators of their time. In a photograph of Pyle and some of his students taken in the summer of 1903, Goodwin, then 22, appears to have been among the youngest.

The students relaxed with impromptu entertainment group singing, charades, and various improvised presentations. Goodwin was credited with being the best ham actor and mimic. His fellow students recalled long afterward his rendition of a bear fight. For a time Goodwin was a studio-mate of James E. McBurney, Samuel M. Palmer and Francis Newton, and a classmate of Clifford Ashley, Gordon M. McCouch, William J. Aylward, Henry J. Peck, Ernest J. Cross, Arthur Becker, Stanley Arthurs and Frank Schoonover. At other times, Philip Hoyt, Alan True, Harry Townsend, George Harding, Walter Whitehead, Thornton Oakley and N. C. Wyeth were among his classmates.

A “Bear” Chance was commissioned by the Nabisco Company for an advertisement. The original oil now hangs in the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

By 1904, Goodwin had his own studio in New York City and was working on commercial assignments. For many years he furnished illustrations for McClwe’s Magazine, Collier’s Weekly and Everybody’s Magazine, and did covers for The Saturday Evening Post. His subjects were always to include wildlife. He painted animals for circus posters and advertisements for various prominent companies, some of which became famous. The original oil of a brown bear devouring a wooden crate of Cream of Wheat now hangs in the Minneapolis Institute of Art, a gift from the Nabisco Company who commissioned it.

Philip Goodwin is sometimes called a “western artist”; indeed, a collectors’ society in Minneapolis who reproduced four of his wax animal sculptures in bronze called him “one of the big three of Western Art” (the other two being Carl Rungius and Charlie Russell). The set of bronzes, a lynx, a sitting bear, awaking bear, and a mountain lion, were offered in a limited edition of 2002 and sold out quickly to friends and members of the society.

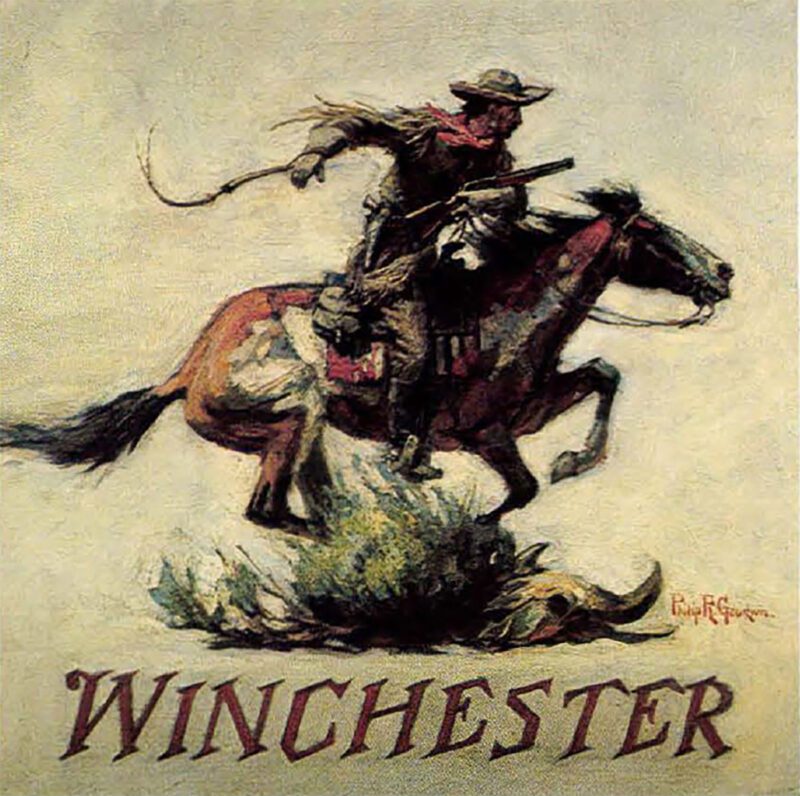

Horse and Rider has been the famous trademark of Winchester Western ArmsCompany (now US. Repeating Arms Company) since 1919.

The American Cowboy in Life and Legend, by Bart McDowell, published by the National Geographic Society in 1972, has as a frontispiece Goodwin’s oil “When Things Are Quiet” — a Montana cowboy on a hillside overlooking his herd. In the same book is Goodwin’s “Early Morning Visitor,” the picture of a camper, still half in his bedroll, taking aim at a huge, snarling grizzly on the rock just above him; the original now hangs at the Thomas Gilcrease Institute in Tulsa, Oklahoma. And Goodwin’s famous “Horse and Rider,” showing a frontiersman on a galloping horse, with a Winchester 73 Carbine — “the gun that won the West” — nestled in his arm has been the trademark of Winchester Western Arms Company since 1919.

But Philip Goodwin was never, and never claimed to be, a true western artist. He was an excellent portrayer of animal life and sporting scenes; inevitably, in an era in which the whole nation was “looking westward” and sportsmen and outdoorsmen in general were fascinated by the special nature of the western wilderness area, some of his paintings were laid in the West.

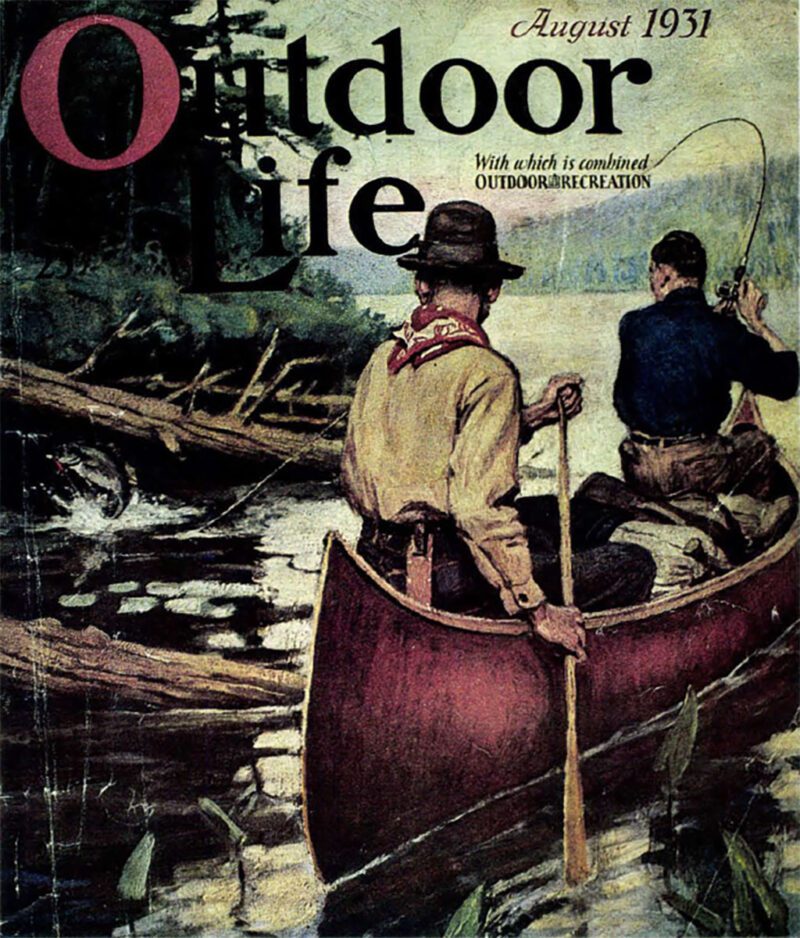

Goodwin illustrations for magazine covers and sparring calendars were a familiar sight to a generation of sportsmen who were fascinated by the western wilderness area.

Goodwin’s sporting paintings commissioned as calendar art and advertisements for gun and ammunition companies — moose hunts, bear hunts and the like — had great appeal. He did many calendars for the Peters Cartridge Company (a division of Remington Arms since 1934), Winchester-Western, Marlin, DuPont and Harrington & Richardson.

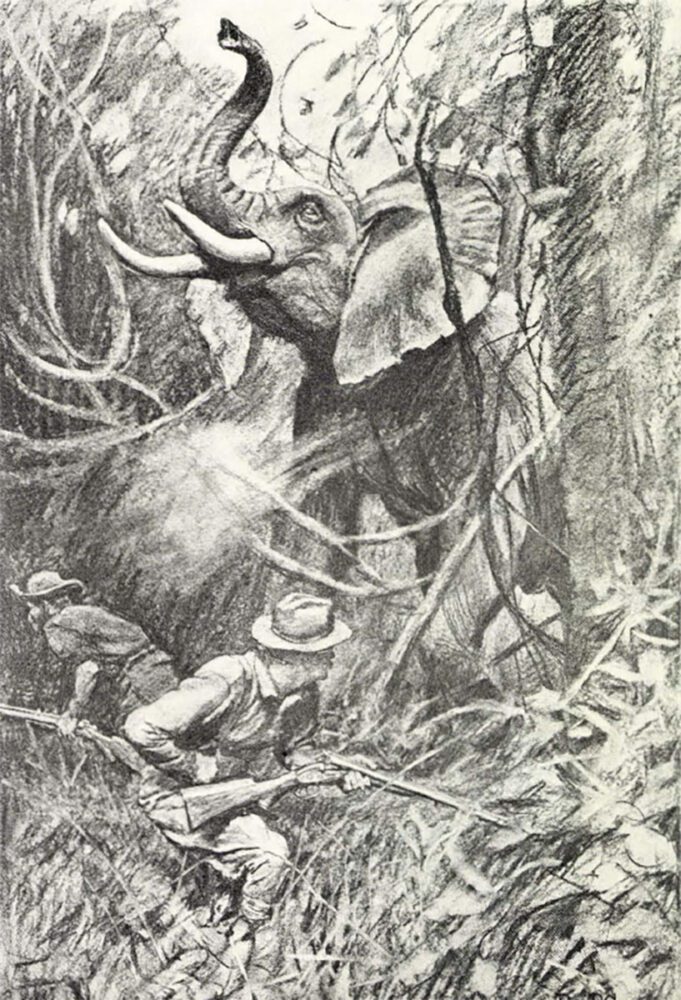

He illustrated many books, both fiction and fact, but all were about animals or the hunting of animals. Best known of his book illustrations are those he created for the early editions of Jack London’s Call of the Wild and Theodore Roosevelt’s African Game Trails. A copy of Roosevelt’s book, which is today in a collection in California, carries the inscription: “To Philip R. Goodwin, with the hearty thanks of Theodore Roosevelt, September 15, 1910.”

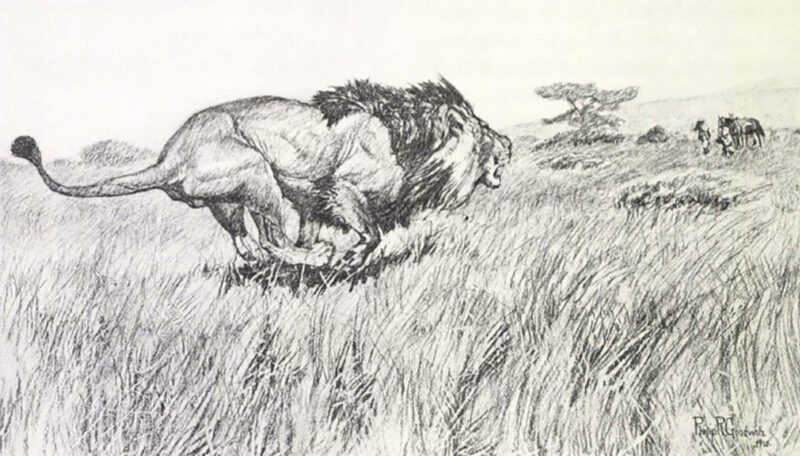

Friends of Goodwin recorded that he spent several weeks in Roosevelt’s home while the ex-president gave vivid, detailed instructions about the scene he wished illustrated. Teddy, crouching and jumping about while demonstrating the animals’ actions, made an unforgettable Sight. According to one account, “Teddy paced off every shot and remembered just exactly how he stood; and he snarled and made faces and skinned his teeth to show how the lion looked. Goodwin wanted to put both man and beast in the foreground of the picture, but Teddy was adamant; he had killed at 150 yards and one hundred and 50 yards it had to be and not a hair’s breadth less. And at one 150 yards either Teddy or lion — whichever was in the background — looked very small.”

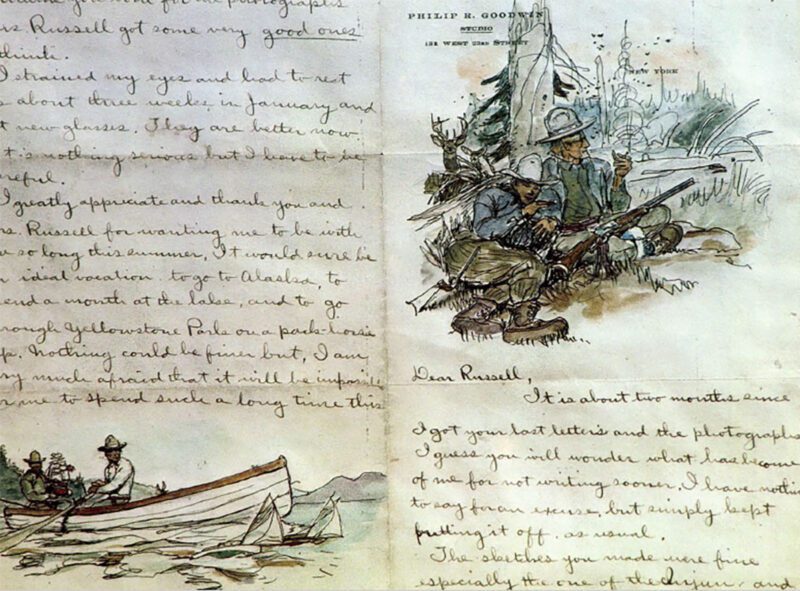

Charlie Russell and Goodwin were friends for many years and often exchanged illustrated letters. The drawings show the two enjoying their vacation.

Roosevelt was delighted with the eight “charging beast” drawings Goodwin furnished — two each of lion and rhinoceros, and one each of leopard, buffalo, hippopotamus and bull elephant. Sportsmen who read African Game Trails can hardly believe that Goodwin was not a member of the African expedition and that he worked largely from Roosevelt’s descriptions and demonstrations.

Goodwin, an ardent outdoorsman and a splendid horseman, spent all the time he could in wilderness areas — the Maine woods, the Colorado Rockies, remote areas of Canada, and with Charlie Russell and his wife Nancy at their mountainside lodge in Montana.

It isn’t known when Philip Goodwin and Charlie Russell first met but by 1906, Goodwin was regularly visiting Russell, who was 17 years older. The two hunted and fished together and remained close friends until Russell’s death in 1926.Goodwin was a favorite of Nancy Russell’s, too. In July 1908, Philip wrote Charlie that he would have to postpone his planned visit with the Russells. He was not “exactly hard up” but felt he should hang on to what money he had. “There isn’t much work around,” he wrote. “The only magazine work I have had since last January were two stories from The Saturday Evening Post and a bear story from Everybody’s, but I have been doing considerable gun calendar work.” At the time he wrote he was struggling with “a gun calendar of a hunter coming around the edge of a log cabin and a big grizzly just rushing out of the door, the man is about to fire from the hip.”

Goodwin, who for some time had been experimenting with animal modeling, working both from zoo animals such as mountain goats and from animals he observed in the wild, wrote that it was “a cinch to work from the real animal” and that he was getting “more and more action” into his figures. Today, his animal bronzes mountain lions, bears, lynx, deer, elk-may be seen in several collections throughout the country and are prized art objects. His trips into the Canadian wilderness inspired some of his most dynamic work, and today more than 30 of his original paintings are on display at the Glenbow-Alberta Institute in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

From African Game Trails.

In the summer of 1910, Austin Russell, Charlie Russell’s nephew (and one of his biographers), visited Charlie and Nancy at their place on Lake McDonald, in north-western Montana, the same time that Goodwin was there. Austin wrote that he was “surprised to find so well-known an artist as the New York animal painter Philip R. Goodwin so modest. He was a slim, black-haired, very boyish fellow — he was 28 or 29 but didn’t show it.”

Austin told “how the wife of an early railroader,” an aspiring authoress who came to Lake McDonald to hire Charlie to make pen illustrations for a book she was writing, viewed Philip: “The first time she saw Goodwin he was working on a model yacht … showing Charlie how to stretch a rubber band from the tiller to the mainsail so that the ship would steer itself and come about in the wind. She thought Goodwin a mere child and when, next day, she saw him making oil sketches of the river mouth-to be used later in calendar pictures — she expressed admiration just as you would to a child and referred to his ketches as ‘pretties’. Goodwin was indignant! And he had to endure endless teasing by Charlie about it. Every few mornings Charlie would ask, ‘Well, my boy, going to make any pretties today?'”

From African Game Trails.

Philip and Charlie worked well together and Goodwin, on one of his first visits to Lake McDonald, enjoyed helping his host build a new hearth and chimney. The two decorated the fireplace by scratching drawings of moose, deer and the like into the wet cement. They put big bear tracks into a wide concrete strip around the cabin. When Russell died, Goodwin helped Nancy Russell with a book of her husband’s letters, Goal Medicine. Will Rogers, who wrote the introduction, autographed a copy “To Phil and Charlie, partners in commercial art crime.”

Austin Russell recalled: “Goodwin was bashful; he couldn’t sing in the daylight, but one night, just after Nancy blew out the lights, he surprised us all by suddenly piping up in a high-pitched, unnatural, embarrassed but resolute voice, and sang an ancient ditty from his childhood:

My father had an old black horse

With a pain down in his thorax,

So he took a great long rubber tube

And filled it full of borax.

He put one end in the horse’s mouth,

In his he took the other;

When he blew in that horse blew out.

And the blow almost killed father.

That summer of 1910, Austin Russell’s pretty young sister also visited at Lake McDonald, and “Goodwin suddenly went soft at the top about her. . . His queer clumsiness was as if he was mentally slipping off his perch. . . but kid sister was too young and Goodwin far to unenterprising for anything to come of it.” By late September all the Russells and guests except Charlie and Philip had departed. The two friends mounted range horses and rode off for several days in the ranch country, stopping overnight at ranch houses. Then Goodwin reluctantly returned to New York.

From African Game Trails.

Philip Goodwin never married. He made his home with his mother until she died in 1924. During his last years he lived alone, except for his dog Jock, in his studio in Mamaroneck, New York. In early December 1935, the 54-year-old artist finished two or three New York assignments and was completing plans for a move to Death Valley, California, when he became ill with pneumonia. On December 11, he was found unconscious in his studio and taken to the United States Hospital at Port Chester, New York. He died the next day. After services at a funeral home in Mamaroneck, his body was taken to Norwich, Connecticut for burial. The New York Times, in a very short obituary, gave his age incorrectly and said only that Philip Russell Goodwin was an illustrator known for his wildlife and sporting pictures and that he had illustrated Theodore Roosevelt’s African Game Trails.

For many years after Goodwin’s death, he was largely ignored in art circles. Austin Russell remembered going through the card index in the art room of the New York Public Library shortly after World War II; there was not a scrap of evidence that Philip R. Goodwin had ever existed. But since his passing he has certainly been “rediscovered,” with his wildlife, hunting and fishing scenes enjoying increasing popularity. Some experts in the field of sporting art are of the opinion that his popularity has been sparked by the realization that modern sportsmen have less and less chance of experiencing the deep-country adventure that Philip Goodwin so delightfully recorded on canvas.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1983 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

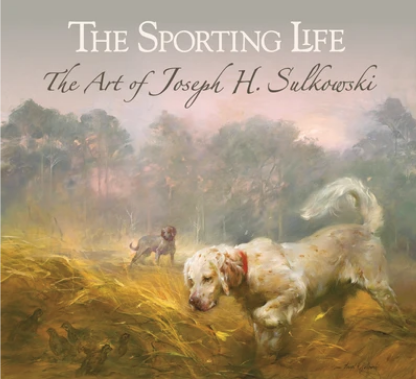

Acclaimed as one of America’s premier dog and sporting artists, Sulkowski shares his personal conversation with the outdoor life in a style of Poetic Realism. Influenced and guided by the hands of the Old Masters, he creates fluid brushstrokes that imbue his canvases with a compelling blend of light, atmosphere, and spatial effects that bring his passion for the sporting life into vivid focus for the viewer. Buy Now

Acclaimed as one of America’s premier dog and sporting artists, Sulkowski shares his personal conversation with the outdoor life in a style of Poetic Realism. Influenced and guided by the hands of the Old Masters, he creates fluid brushstrokes that imbue his canvases with a compelling blend of light, atmosphere, and spatial effects that bring his passion for the sporting life into vivid focus for the viewer. Buy Now