The old knife was one of those singular objects in life that can never be replaced, an inseparable part of what and who you are.

Knives are like friends: you know many over the years, but it’s rare to keep one for life.

My first was my father’s folding Camillus. I was ten when he gave it to me, and saw it as a rite of passage, a sign that I was finally trusted with the accruements of manhood.

“Don’t be an idiot and cut yourself,” Dad said.

My father was an electrician who used the knife to strip miles of insulation from electrical cables. He also used it to scale a million perch, clean a thousand pheasants and skin hides from untold numbers of deer. He constantly whetted the knife to keep it sharp, and a lot of steel was worn away. By the time he gave it to me the single blade resembled a porcupine quill.

Still, it was a real knife and I immediately set about whittling. The first item I whittled was my thumb. After Mom finally stemmed the bleeding and my screams she sent me off to bed. I emptied my pockets on the nightstand: baseball cards, marbles, a steel penny and my beloved pocket knife. In the morning everything was there but the Camillus. Like most knives, it had vanished.

“I can’t find my knife,” I told Mom.

“Maybe it will turn up,” she said. And it did, 30 years later, in a box she had used to save my childhood artifacts.

I grew up in a big family where most of the things I could call my own were hand-me-downs or homemade articles.

The latter included a flat file from my father’s tool shed. I reduced it to molten metal on a hot plate before grinding it on an emery wheel, trying to shape a bastard file into a Bowie knife, but ending up with an ice pick.

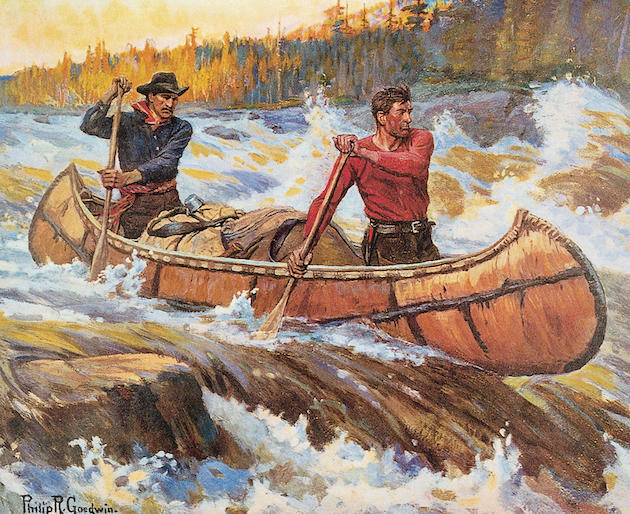

“Red Demon of the Forest” by Philip R. Goodwin.

I was 12 when I started hunting, and Moochie was my usual companion; he could talk me into anything. After trying to clean a rabbit with my homemade ice pick, Moochie insisted we buy a real hunting knife. We strode into Irv’s Army Surplus Store where hundreds of knives made of cheap Japanese steel lay gleaming like El Dorado. Moochie favored a World War I trench knife, the sort that had brass knuckles for a handle — you never knew when Prussian soldiers might storm your duck blind.

Irv offered me a British Commando model that looked like the daggers Errol Flynn clenched between his teeth in the movies. I settled on an imitation Ka-Bar and Moochie immediately talked me into playing “stretch.” He pulled the knife from its sheath and on his first toss struck a rock, curling the blade into a giant fish hook.

“I can fix that,” Moochie said. We went into Dad’s shed and turned on the emery wheel. Ten minutes later I owned another ice pick. After that knives came and went like pimples. Each cost $1.29 and were made by the Imperial Knife Company.

Every smoke shop kept a display case of Imperial Knives on the counter, usually right above the comic books and candy bars. All were ill-designed and incapable of holding an edge. The knives never sliced or cut — they sawed their way through squirrels.

Occasionally I’d buy a chunky, inexpensive Case knife. They were the cutlery version of girls I dated whose best feature was “a nice personality.” The more desirable models had Chevrolet tastes, and I was on a Schwinn budget. Like girls with nice personalities, Case knives inflicted serious wounds when handled improperly.

We lived along the feral edge of a Midwestern town, where the factories stopped and woodlots began. It was assumed I’d work in a mill like everyone else, but all my dreams for the future had to do with the woods.

The day after we finished high school Moochie and I said goodbye to our families and left for the canoe country of northwest Ontario. While friends took jobs on assembly lines to save money for weddings and college, Mooch and I were determined to build a log cabin and become backwoodsmen. We were clueless, not only about the immense difficulties of wilderness life, but also why we were fleeing an easy and comfortable existence.

Part of it, I suppose, was rebellion: We resisted convention and the idea of being like everyone else. The adults we knew were content with familiar routines, accepting tintype copies of the lives their friends and neighbors shared. I couldn’t bear the thought of routine and accepting a life I never made or chose.

“Into New Country” by Philip R. Goodwin.

Two weeks later, lost and living on suckers and berries, we wandered into a Hudson Bay Company store north of Lake Superior. The post was like something out of a Jack London story — a small store filled with canoes and Indians, trade goods and traps, guns and moccasins, furs and fishing tackle, snowshoes, tump lines, and Duluth packs. Entering the Hudson Bay store was like stepping into another world; from that instant I knew the life I wanted and where I would live it.

After buying all the canned food our canoe could hold, I looked for some small, inexpensive item to remind me of my visit. I found it in a $2 trade knife. I think it was a kind of trout knife — if trout knives weighed as much as decoy anchors. Rugged and primitive as the land in which I’d found it, it was a straight, thick, 3¼-inch blade with so much carbon content that the steel was already as gray and discolored as an Indianhead nickel.

The keen edge easily shaved hair from the back of my wrist — and much of the rest of my arms. There was no hilt and the handle was a chunk of rough wood dipped in red paint. The rigid plastic sheath lacked a tab to hang on a belt, so I simply stuffed the sheathed knife into a back pocket. There it would stay for years to come.

I purchased the knife, we returned to our canoe, pointed the bow south, and headed home. Moochie took a job in an American Motors plant, but soon the red knife and I were back in the North, setting about the long process of making a life in the Lake Superior woods.

At first the red knife was used for the usual things a young male will do when living alone in the backcountry: whittling toothpicks and prying caps off beer bottles. Then — older, wiser and out of necessity — I used it to dress and butcher deer, fillet hefty pike, cut tent stakes, set traps, skin fur and perform first-aid on broken paddles and people.

That first winter I was crossing a frozen lake when the ice cracked and I plunged into the frigid, lambent depths. I hit bottom and pushed off, luckily coming up through the hole where I’d fallen, but each time I clawed at the ice to pull myself free of the water my fingers slid away as if greased. I grabbed the red knife, held it like an ice pick, and drove the blade into the ice.

I kept punching at the frozen surface until the knife stuck like an anchor. I wrapped both hands around it and pulled myself to safety.

The following year I made the mistake of waiting until dusk to pick a place to camp and was forced to pitch my tent in a spot fishermen had used all summer. The place reeked. I hurriedly fried up walleyes and turned in to escape the flies and stench.

I dozed until the tent flaps were parted by a black bear.

“Yeooowww!” I shouted. “Get outta here!”

The bear stepped forward, placing a heavy, padded paw between my legs. I grabbed the red knife and, holding it like a hammer, brought the butt down hard on the animal’s nose. The bear bellowed like a wounded bull, spun around and fled.

“Nothin’ scares a bear like a good smack on the schnoz,” an old trapper later told me. “They’re just like bullies: hit ’em in the nose and they’ll run every time.”

I was slowly learning how to live in the North. In the process the red knife did everything from picking my teeth and blazing trees while cruising timber to cutting wildflowers for my new wife and teaching our young son the elements of “stretch.” Over time it took on a quality and character that were irreplaceable.

Eventually the handle split. It was held together with duct tape for years until it came apart while I was cleaning pike beside an Arctic stream. I last saw that red handle bobbing on the amber current of a wilderness river, floating away toward Hudson Bay, which to my way of thinking is where it belongs.

Nowadays I keep the knife in a desk drawer and occasionally come across it when scavenging for stamps. Every time I see that tarnished blade I’m reminded how much of me is contained in its steel and how, in a real sense, the life I have was fashioned by that knife.

The red knife is not a mere token or memento. It means more to me than my retired Stevens and rusty wolf traps. Like a wedding ring, it’s one of those singular objects in life that can never be replaced because it is more than the thing that is seen — an inseparable part of what and who you are.

Over the years I’ve owned my share of Gerbers, Bucks, Brownings and even a Russell, but none ever acquired the sense of intimacy I feel toward the knife I keep in a drawer. Home is still a wild place: Lake Superior literally lies in my backyard and roadless wilderness is a short walk away. A teenage voyage toward self-discovery led me here; a knife from that trip keeps me pinned in place. And although I now know all of us, everywhere, are bound to routine, the red knife at least gave me the chance to make and choose my own.

Let this Bob Loveless tribute knife speak to your own refined style with its balance, function and beauty. This drop point hunting knife makes field dressing game an almost effortless task. Buy Now or Shop more knives at the Sporting Classics Store.

That was a great read – thanks!