A growing number of artists are making contributions to our world that reach far beyond the framework of their paintings.

Some artists are more socially significant than others, and it has more to do with how strongly they believe in human or environmental conditions than how well they paint. You can recognize many of them as well as I can. Just list the twenty wildlife artists you think have contributed most to our understanding of the environment. Most likely, your list will include such artists as John J. Audubon, Roger Tory Peterson, Sir Peter Scott, and more recently, Robert Bateman. While many other artists have contributed in a variety of ways, for me these artists provide recognizable benchmarks in the evolution of wildlife art. They’ve each contributed significantly to human perceptions of our world, but more importantly, their concepts reach well beyond the framework of their art. They’ve become spokesmen for the issues of their time.

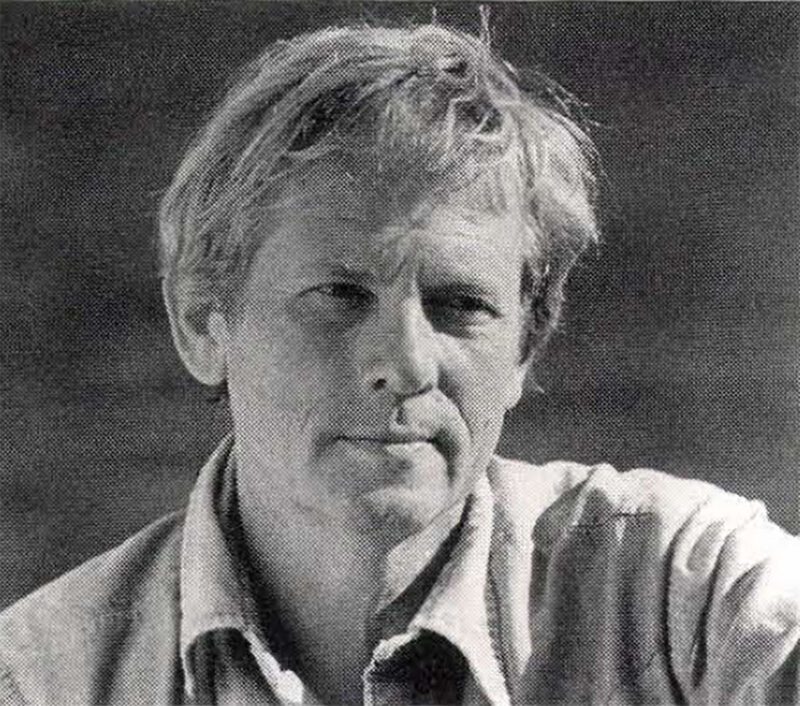

The popular Canadian artist has dedicated a number of his wildlife prints to conservation causes.

Audubon was an explorer as much or more than he was an artist. He chronicled the vast American West. His work fulfilled a significant need that reached well beyond the market value of each image. Through his art, he became an expert about his subjects as much as any naturalist during that period of time. Roger Tory Peterson added a new dimension. He made bird identification something of interest to common folks and not just scientists. He has done as much as any artist to make nature study an enjoyable adjunct to outdoorsmanship. He too has become famous more as a naturalist than as an artist. His art only added to his many contributions.

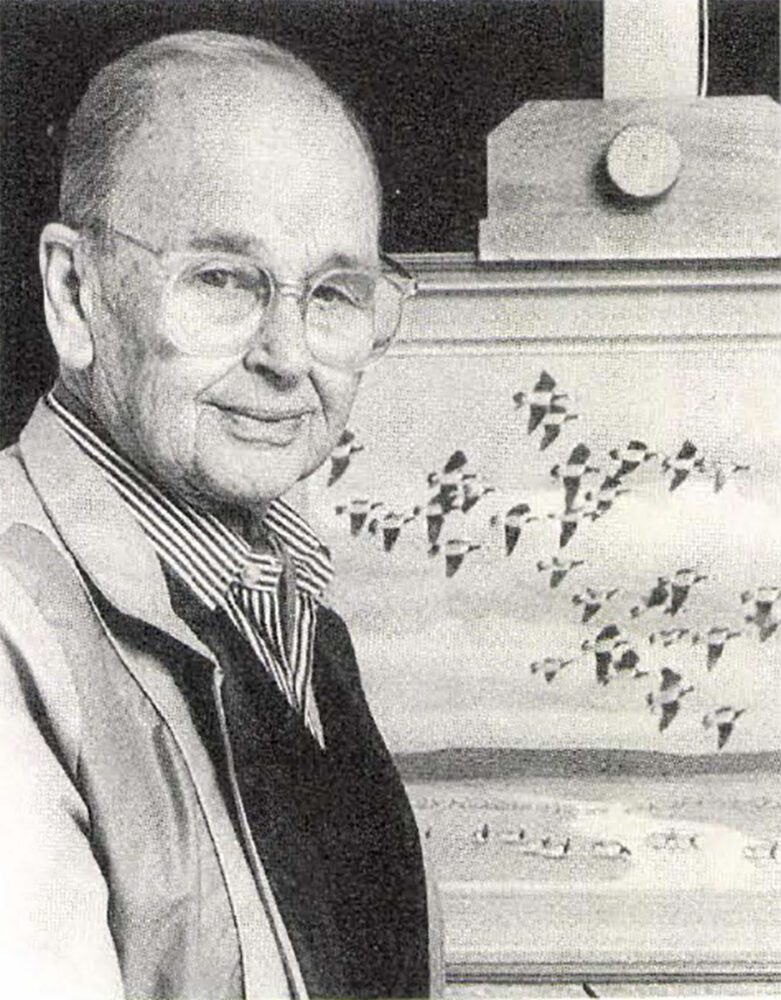

Sir Peter Scott’s contribution to environmental awareness has reached into other realms. His work echoes broader ramifications of the natural world. He used his art to speak of the panoramas of life, not as images in themselves but as adjuncts to those ideas and ideals he promoted beyond art. He was much larger than his art because of the issues he raised.

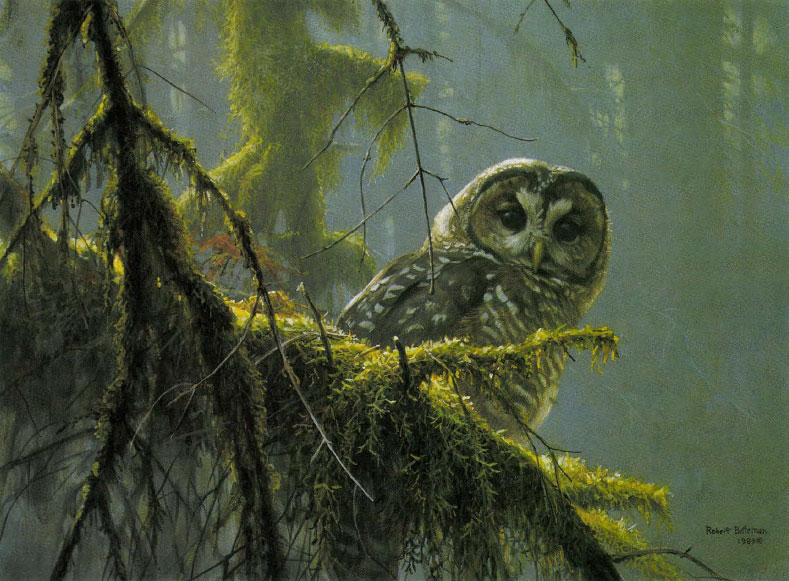

The artistic quality of Robert Bateman’s work speaks for itself. As with Sir Peter Scott, some of his art offers a broad panorama of nature. Others offer unique, intimate views. I dwell on Bateman because closer analysis of his designs and subjective components of his paintings discloses keys to his greater contribution as an educator and naturalist. His paintings are visual hints of natural dynamics, a play of rhythms and harmonics that toy and tantalize the conscious edges of the viewer’s psyche. This, too, is the role Bateman has chosen for himself as a person. He probes, pulls, and tantalizes us to begin thinking about our surroundings. He does this when challenging other artists to perfection, and he does it as a fellow human trying to motivate us on environmental issues! His concerns beyond art are reflected in his comments that he’s more willing to spend time addressing environmental issues than art issues. In this way, he has been a leading force during the ’80s.

To a significant degree, Bateman’s acceptance as spokesman of subtle designs, artistic and environmental, has created opportunities for a great many other artists as spokespersons in the ’90s. There’s a growing need for understanding and appreciating the environment on subtle levels, a need to begin dealing with those delicate issues that artists so adroitly address as visual poets. We’re beginning to reach beyond commercialism toward resolving our problems, and more wildlife artists than ever before have already addressed these kinds of issues in their work. And, more than ever before, many are making dramatic visual statements. Now they’re beginning to voice opinions in other ways. A few are taking strong stands on environmental issues, as well they should. Most are appropriately trained for the task.

Many of us in wildlife art are formally educated in the environmental sciences or some aspect of wildlife management. If not formally trained, we’re fairly astute, self-taught naturalists. Some of us are former fish and game people or habitat researchers who have left the political frustrations of state or federal management programs fora more direct assessment of the issues through art. Others are former high school or college science teachers who have quit the formal teaching profession to reach the general public more directly with a barrage of visual messages. Just by the nature of our work, wildlife artists become wilderness philosophers, storytellers, and visual poets. We’ve long been qualified as spokespersons for major issues, but little recognized for our potential. That’s changing.

Now, more than ever before, artists are forming partnerships with wildlife agencies and organizations in ways that add new and interesting twists to the old static shoulder-to-shoulder booth arrangement of art shows. We’re helping turn these exhibits into full-fledged, multi-media programs of interest to everyone, not just art collectors. We’re combining slide and movie programs with the best attributes of art exhibits and the excitement of public participation found in the many sportsmen’s shows held all across the country.

Twenty Whistling Swans Came Out Of The Mist, by the late Sir Peter Scott of England. Scott was involved in a variety of conservation projects, from whales to wild pandas. This artwork and Batemans Spotted Owl are reproduced courtesy of Mill Pond Press, Inc., Venice, Florida.

As an artist and writer for the past 20 years, I’ve done my share to promote these expanded concepts. In 1984, I organized a Wildlife Art Plan-of-Action Program initially as an artists’ network for sharing ideas. The concept was later expanded through my feature columns in Wildlife Art News magazine and articles such as this one. Our artists’ symposium scheduled for Alaska in mid-May,1990, is another example. Featuring renowned artists like England’s Alan Hunt, Englishman and now U.S. resident John Seerey-Lester, Morten Solberg, award-winning sculptor Terri Malec Barnett, Wildlife Art News Editor and Publisher Robert Koenke, myself as organizer, and many artists from all across the country, it offers us the opportunity to coordinate our efforts. It gives us an opportunity to coalesce ideas and ideals, and assess ways in which we can make our work more socially significant and ourselves more responsible members of society.

While many wildlife artists tend to think this means addressing only environmental issues, it doesn’t have to be that limited. There are hundreds of ways to make art and artists more effective proponents of a broad range of social issues. In 1984, I designed the concepts of a traveling art show to be used as part of a statewide industrial development program-art as the centerpiece for a public forum between regional residents and leaders of various industries. It was side-tracked by a lack of public funds to get it started. In 1985, a first National Wilderness Art Show was sponsored by the Wilderness Research Foundation at Colorado State University in conjunction with a scientific symposium. Unfortunately, artists were not made part of the conference, and the show itself was segregated by five city blocks from the site of the scientific meetings. The concepts themselves were valid.

I’ve long pushed for a greater role for artists as spokes persons in the many national-level, pay-for-space shows sponsored by state habitat foundations or regional wildlife groups. One organization that has groomed this kind of working relationship with artists is Tacoma, Washington’s Snake Lake Foundation. They sponsor the annual Pacific Rim Wildlife Art Festival and continue to add new and far-reaching working arrangements with artists. No doubt, future shows will incorporate many of the seminar and symposium concepts I designed for our Alaskan Symposium.

The same approach has been used by many wildlife artists as part of their one-person gallery or museum shows. Many include outdoor adventure slide programs with their art exhibits-programs appropriate for anyone interested in the out-of-doors, but who may not be interested in art. Many of us trained in disciplines other than art treat our paintings or poetry, our sculpture or prose, as a means to an end, rather than end products in themselves. My experience in art and writing gives me some technical proficiency in those media, but I continue to be driven more by what I say than how I say it. It’s little different than many of us who started in science and then turned to more graphic forms of environmental education. That’s the name of the game: communication and education. And artwork is but one means of communicating ideas.

The same approach has been used by many wildlife artists as part of their one-person gallery or museum shows. Many include outdoor adventure slide programs with their art exhibits-programs appropriate for anyone interested in the out-of-doors, but who may not be interested in art. Many of us trained in disciplines other than art treat our paintings or poetry, our sculpture or prose, as a means to an end, rather than end products in themselves. My experience in art and writing gives me some technical proficiency in those media, but I continue to be driven more by what I say than how I say it. It’s little different than many of us who started in science and then turned to more graphic forms of environmental education. That’s the name of the game: communication and education. And artwork is but one means of communicating ideas.

John James Audubon, Roger Tory Peterson, Sir Peter Scott, and Robert Bateman give us but a few examples of what can be done. In retrospect, their roles in the evolution of environmental statements are obvious, but what lies ahead? What are the artistic and artists’ roles for the future? Only those of us willing to probe the options will know. One thing for sure, there are more than a few wildlife artists willing to share ideas about environmental and social issues beyond their art. More than a few want to plan new and innovative projects with fish and game agencies, habitat and wildlife rehabilitation organizations, educational leaders, and social and industrial planners across the broad spectrum of human endeavor.

Now more than ever before, artists are becoming integral parts of the process as thinkers, planners and communicators of vital issues, their contributions reaching far beyond the framework of their paintings.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1990 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.

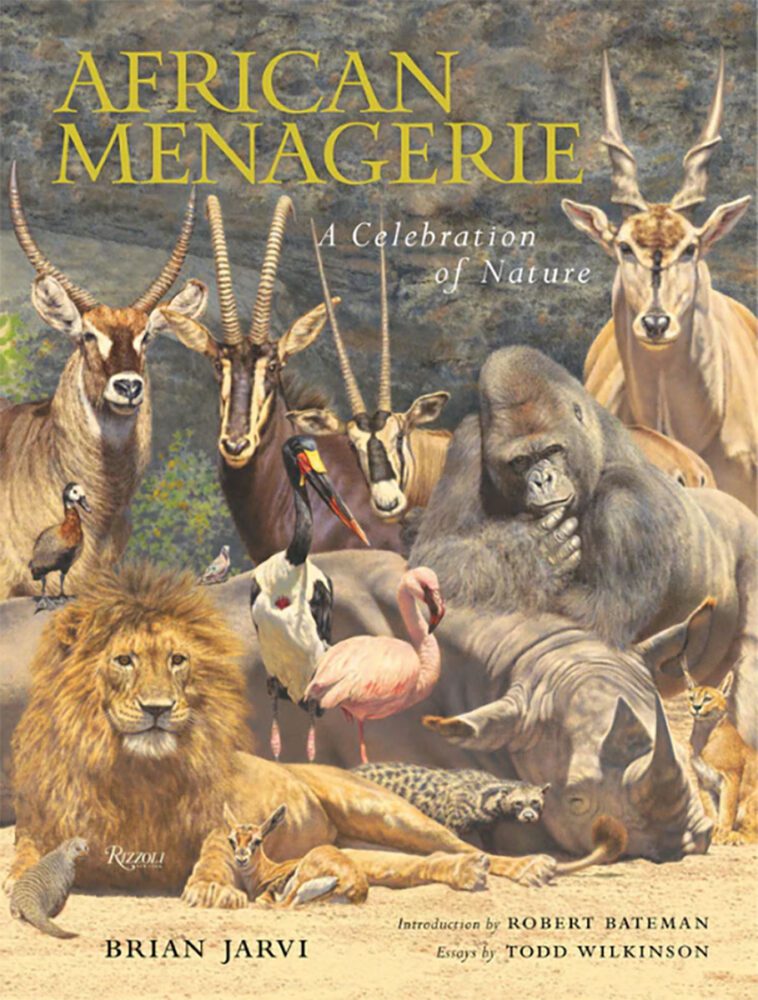

Depicting more than 220 African species, the stunning large-scale mural African Menagerie is artist Brian Jarvi’s masterwork. Lavishly reproduced in an oversize format with a gatefold, this book brings this landscape masterpiece to the conservationist, lover of Africa, and fan of wildlife art. In oversized color reproductions, the book African Menagerie offers readers a look at the finer details of the realist renderings of the animals and birds across the seven panels and thirty feet. There are also reproductions of the animal studies Jarvi created in the seventeen years leading up to the final work. Buy Now

Depicting more than 220 African species, the stunning large-scale mural African Menagerie is artist Brian Jarvi’s masterwork. Lavishly reproduced in an oversize format with a gatefold, this book brings this landscape masterpiece to the conservationist, lover of Africa, and fan of wildlife art. In oversized color reproductions, the book African Menagerie offers readers a look at the finer details of the realist renderings of the animals and birds across the seven panels and thirty feet. There are also reproductions of the animal studies Jarvi created in the seventeen years leading up to the final work. Buy Now