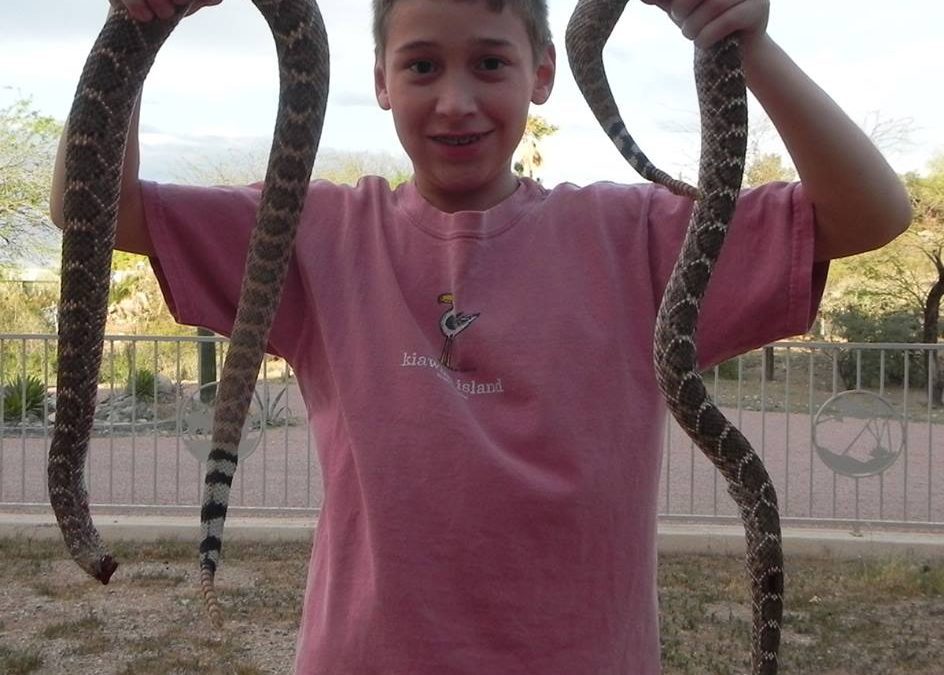

“You boys got to keep your eyes peeled for those diamondbacks,” Pierre said. He was butchering fish by the light of a Coleman, flounder fresh from the creek.

“This time of year, they lookin’ for anything warm. Crawl right in your sleeping bag.”

Pierre was fixing to put one over on Spanky. Spanky didn’t truck much with snakes. Pierre and Spanky were buddies, down on St. Phillip’s Island, South Carolina, 50-odd years ago.

There was Jehovah God, our Sweet Lord Jesus, Moses, assorted prophets both major and minor and then Pierre. He was a riverman and he knew more about this land than God forgot.

Dark of the moon. Pierre went gigging on the lowtide slack-water. Flounder and grits for breakfast about dark-thirty, then loose the hounds at first light.

Six inside in three Marine Corps surplus double-deckers. The rest had the ground, fine till the fire went out. You shat in an indifferent outhouse, spat your toothbrushing off the dock into the ebbtide water.

Bucks only in those days and the snaggly island rag-horn racks were nailed here and there along the walls, inside and out. In between were shirt-tails cut from the hunters who missed, labeled day, time and place, the entire back run of the shirt, mostly, from the tail clean up to the collar.

Pierre threw the last of the flounder in the cooler, splat. He was a good man with a gig. “I’m fixing to turn in. You boys keep your eyes peeled for those rattlers.”

But the rattlers had all denned up at first frost, two weeks past. Pierre stuck a garfish on his flounder expedition, cut off the fins and tail and stuffed it into the bottom of Spanky’s sleeping bag. Pierre turned the Coleman low, but not off while everybody kept one eye on Spanky.

Spanky loaded his shotgun, an Ithaca pump, and leaned against a tree within easy reach, peeled the top of his sleeping bag, eased into it, wiggled down into to it, briefly comfortable.

But then his sock-foot toes found the lump of garfish.

You could see it in his eyes, see the sweat beading his brow, even with the frost about to crinkle the broomsedge the way it was and the sea fog creeping, creeping up Trenchard’s inlet as the island cooled. The hounds were tethered here and there to palmetto trunks roundabouts. Their eyes caught the firelight and their breath hung in the air. They would strike good scent at sunrise.

But still, Spanky sweated.

First six inches, Spanky moved like a slow glacier, second six like a box terrapin at full gallop. And then with a sudden leap he was clear of the bag. He snatched his shotgun—blam, blam, blam—three loads of buckshot as fast as he could work the action, which was damn quick. Feathers flew, the hounds erupted into a leaping, lunging, howling crescendo, nearly outdone by the hoots and guffaws from the hunters.

We hushed the hounds with fish heads.

Spanky killed a fat forkhorn at the Wagon Box stand about daybreak, then everybody was sorry they had treated him so poorly.

At 92, Pierre remembers it differently. It was a rubber snake, not a garfish, but the terror was much the same. And there were a lot of deer killed at the Wagon Box. It was all half a century ago, so that’s okay I guess.